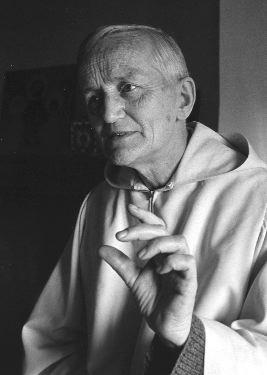

The making of Taizé Roger Schutz (1915-2005): Roger Schutz (1915-2005)

Almost everyone engaged in the search for Christian unity has at some point received important impulses from the Taizé community. And whoever speaks of Taizé is bound to speak of Roger Schutz (1915-2005), whose intuitions and initiatives turned the community into a focus and center of the ecumenical movement.

The origins of Taizé lie in World War II. In the face of the horrors of war, confessional boundaries—already undermined by earlier developments—became more and more obsolete. Three years after the armistice, the World Council of Churches was founded in Amsterdam, and encounters and exchanges between Protestants and Catholics also became more and more frequent. The Taizé community built on this experience.

Schutz, the son of a pastor of the Swiss Reformed Church, studied theology in Lausanne and Strasbourg. In 1940 he moved to Taizé in French Burgundy and was soon joined by a group of companions. In 1949 they decided to engage in a radical commitment and to found a monastic community. (A similar initiative had been taken even earlier by a group of Reformed women who had started a community in Grandchamp near Neuchâtel in Switzerland.) They renewed the tradition of the daily prayer hours. For their liturgical life they owe much to the liturgical renewal movement in the Reformed churches of French-speaking Switzerland.

During the first years of its existence the community was primarily sustained from the Reformed side. Soon, however, the Roman Catholic Church began to take interest in Taizé. At the end of the 1950s, when Pope John XXIII announced the Second Vatican Council, the community became a center of the forces promoting the ecumenical opening of the Roman Catholic Church.

My first visit to Taizé fell in this period. Prayers were still held in the old village church. There was an atmosphere of freshness and expectation. The spirituality of the community was inspired by Frère Roger. The essential features of his spirituality are well expressed by the title of one of his numerous writings, Living Today for God (Vivre l’aujourd’hui de Dieu). For him the ecumenical movement was nothing other than letting God act here and now. Christ’s resurrection, the light in the intimacy of our hearts, is the center which joins us in one communion.

The community received an invitation to send observers to Vatican II. Frère Roger’s primary interest was the event of the council itself. He largely left the theological debates and disputes to Max Thurian, the subprior of the community, while he sought through personal contacts to win the council fathers to the cause of the ecumenical movement. Hundreds of bishops were received in the small Taizé apartment in Rome.

Perhaps precisely because his primary concern was not with the confessional differences, Frère Roger was open to other aspects of Christian witness. He was touched by the voice of the bishops, especially Dom Helder Câmara, who called on the council to show more solidarity with the poor. Already during the Vatican Council, Latin America was becoming a new emphasis of the Taizé community. Environmental issues, however, remained outside Frére Roger’s horizon.

In connection with Vatican II, Frère Roger issued an appeal to the youth of the churches. Was it possible, he wondered, to supplement the council with an ecumenical youth council?

The response went beyond all expectations. The appeal did not result in a formal youth council, but Taizé became the meeting point of thousands of young people, especially at Easter, with more and more young “pilgrims” participating in the prayers of the monastic community. To many, including my own children, these encounters were inspiring. Frère Roger and his community were able to create an atmosphere that combined simplicity, freedom and commitment.

Taizé has not lost its attraction. An important dimension of the community has been its artistic activities. Even in the first years of its existence it was known for its pottery and its stained glass. The melodies produced by Frère Jacques Berthier are sung not only at Taizé but all over the world.

The experience with young people led Taizé to organize youth gatherings in various countries. I was actively involved in one of these gatherings. In preparing for the 50th anniversary of the first World Conference on Faith and Order, I asked Frère Roger whether he would be willing to amplify the celebration with a youth gathering. In 1977, 3,000 young people participated in an unforgettable vigil in the cathedral of Lausanne.

Of special importance were the youth gatherings in Eastern Europe. I know of many for whom the link with Taizé helped to keep the flame of faith alive. Collaboration with Frère Roger was not always easy. He had developed his own theatrical style, and the way he staged his appearances in public was sometimes a little irritating.

The influence of this small group of monks has been and continues to be immense. In Taizé, young people experience Christian community across the boundaries of the confessions. But can the confessional differences be overcome by this temporary experience? The confessional structures, especially of the Roman Catholic Church, have turned out to be much more resistant than they appeared for a short while during the 1960s. The “free space” of Taizé could not be easily transplanted into the daily life of the churches.

A conversation with Frère Roger a few months before the opening of Vatican II is still alive in my memory. “Now,” he said, “it is the calling of the Reformed church to contribute to the renewal of Catholicism.”

I wondered: “Does the true challenge not rather consist in working together, Protestants and Catholics, toward a new form of catholicity?”

“Perhaps,” he answered, “but the way to unity leads through the renewal of the Roman Catholic Church.”

He consistently followed this road, and it was almost inevitable that from year to year and from decade to decade the community moved more in the universe of the Roman Catholic Church. The Reformed origins became gradually less evident, and the renewal of the Reformed tradition was no longer the purpose and theme of the community.

But, in fact, the Reformed background continued to be essential for the mission of the community. It was the freedom provided by the Reformed tradition that made it possible to build the “free space” in Burgundy. How quickly the initiative would have come to a standstill if the community had been subjected to the authority of the Roman Catholic Church! Without the basis of Reformed freedom, the vision of Frère Roger would not have been capable of going beyond mere intentions. The awareness of this gift should perhaps have led him to witness to the Reformed heritage and its fundamental convictions with a little more gratitude and care.