The Anglican Communion's only Hmong-majority church thrives in Minnesota

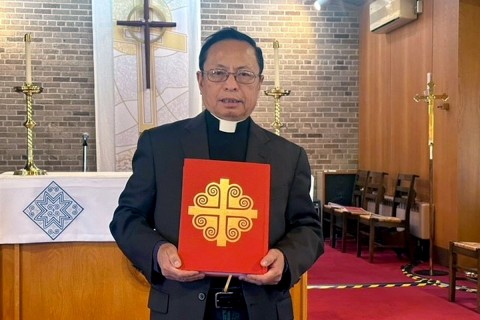

Wa Meng Lor holds the English-Hmong book of Sunday Gospel readings he created. (Courtesy photo)

Compiling a book of the Sunday Gospel readings in both English and Hmong is just the latest way Wa Meng Lor has helped members of the Church of the Holy Apostles in St. Paul, Minnesota, join their Hmong roots to their life in the United States.

Since 2019 Lor has been the vicar of the only majority-Hmong congregation in the Episcopal Church. Its members have roots in Laos, a Southeast Asian country that shares a border with Vietnam. And, he believes, his is the only majority-Hmong church in the Anglican Communion.

Lor started the parallel-text project during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic when in-person services were suspended and he found himself with extra time on his hands. The church covered the cost of printing 10 copies of the large book, bound in dark red with a traditional Hmong symbol printed in gold on the cover.