Shadows of a saint

In 1963, W. H. Auden reported his weary experiences on a lucrative U.S. lecture tour in the wry poem “On the Circuit.” It was grim maintaining a smiling face while meeting so many gushing strangers, but occasionally there was “a blessed encounter, full of joy . . . With, here, an addict of Tolkien / There, a Charles Williams fan.” The number of devotees of J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis proliferated enormously over the following decades, and that boundless enthusiasm spilled over to any and all of their associates, including Williams. A rising tide lifted all Inklings.

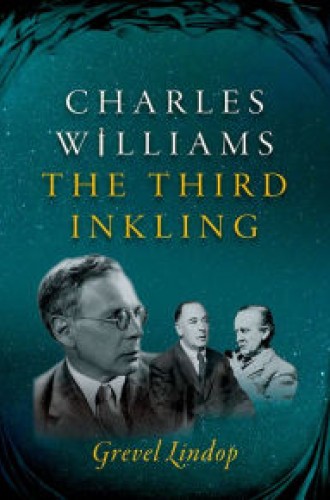

Many contemporaries regarded Williams (1886–1945) as an unalloyed genius and polymath. He was at once theologian, mystic, poet, novelist, editor, playwright, and critic, not to mention being an esteemed spiritual mentor and (possibly) a living Anglican saint. Lewis was deeply influenced by him to the point that the figure of Aslan in the Narnia Chronicles was borrowed intact from the angelic archetypal figure of Williams’s novel The Place of the Lion. Meanwhile, Lewis’s novel That Hideous Strength is often regarded as more Williams’s work than Lewis’s. Some of us would quibble about relegating Williams to the rank of merely third among Inklings.

T. S. Eliot also fell under his spell. The better you know Williams’s all too seldom read dramas, the more startled you might be at the numerous clear echoes of his work throughout Four Quartets. Auden himself said he owed his Christian conversion in part to contact with Williams.