The Congregationalist burden

In 1909, Geraldine Taylor of Medina, Ohio, told her fellow church members about a time when a leading businessman came to worship one Sunday morning and found his pew occupied by three ladies. The businessman opened the pew door, rapped his cane on the floor several times, and expected the women to depart. They remained. He shut the door, reversed course, and walked out, his children trailing behind him the entire time. When he reached the entryway, he turned around and proclaimed, “It is very well for people to keep their places.” One of the women in the man’s pew was none other than his own mother, and the businessman dutifully returned to Medina’s Congregational Church the next Sunday.

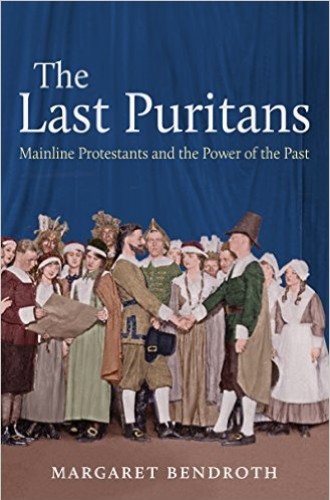

In The Last Puritans, Margaret Bendroth, executive director of the Congregationalist Library, recounts the history of American Congregationalism from the early 19th century through the 1957 merger that created the United Church of Christ. Observing the outpouring of attention that evangelicals have received from historians and pundits over the past several decades, Bendroth intends to rescue liberal Protestants from both scholarly anonymity and the disdain that almost inevitably accompanies numerical decline. “Mainline Protestants,” she writes, “are not simply failed evangelicals, traditionless and compromised, but people with a particular historical burden.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Bendroth carefully reconstructs the varied and often contentious ways that many generations of Congregationalists wrestled with their Pilgrim ancestors’ theological and ecclesiological inheritance. Like Geraldine Taylor, many of them spent decades coming to churches tightly bound into the fabric of their communities. Some resisted new theological ideas, denominational initiatives, and ecumenical projects, while others embraced them. But for a long while, theological conservatives and their liberal counterparts coexisted rather peacefully. Many individuals simply continued coming back the next Sunday amid sometimes disorienting change.

In 1820, Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster delivered an oration in Plymouth’s First Church on the bicentennial of the Mayflower. For Webster, Plymouth Rock was not merely a Congregational or New England symbol. Instead, it was a spot at which all Americans could “hold communion at once with our ancestors and our posterity,” and the birthplace of American democracy, religious freedom, and industry. But while many white Protestants venerated the Pilgrims, their legacy was anything but unifying. Two months earlier, a group of theological liberals at Plymouth’s First Church had publicly renounced several tenets of Calvinism. In the years ahead, Unitarians and their more orthodox Congregationalist counterparts would joust repeatedly over which group best represented the Pilgrims’ legacy.

The Congregationalists fiercely defended their claims to the Puritan past, but they hardly knew what to do with that history. By the mid-19th century, as Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian numbers swelled, Congregationalists debated the authority of past practices and wondered whether they should create denominational structures in seeming contradiction to Congregational polity. By this time even the most orthodox Congregationalists adhered to attenuated versions of Calvinism. At an 1865 council in Boston, delegates heatedly discussed a proposed statement of faith that enshrined “the system of truths which is commonly known among us as Calvinism.” In the end, the delegates instead affirmed “the faith and order of the apostolic and primitive churches held by our fathers.”

Despite reservations on the part of some, in 1871 Congregationalists formed the National Council of Congregational Churches, taking a decided step away from absolute local independence. Over the next half-century, Congregationalism gradually moved toward what Bendroth terms a new “version of denominational life, symbolically tied to the Pilgrim legacy but in reality defined by a progressive social agenda and the modern methods of parliamentary procedure.” Bendroth documents that despite that course, theological conservatives maintained a strong presence within the denomination, which largely avoided heresy trials and the rancor of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy.

Two developments irreparably widened fissures between progressives and traditionalists: the 1934 formation of the Council for Social Action and the long years of contention over the denomination’s merger with the Evangelical and Reformed Church. (In 1931, Congregationalists had merged with the Christian Church, a much smaller and less contentious affair.)

For conservatives, both the Council for Social Action and the proposed merger raised the fear not only of apostasy but also—during the New Deal and early cold war eras—of centralized power. In 1948 some of those conservatives left to form the Conservative Congregational Christian Conference. For many other Congregationalists, the merger stoked “fears of denominational extinction.” Merger proponents, by contrast, believed that the step represented long-cherished values of unity and irenicism.

Bendroth not only recovers the details of denominational infighting but richly documents a religious culture whose adherents often quietly sorted through competing attachments to theological purity, independent polity, and Christian unity. They did so both burdened and inspired by 17th-century Puritans, whose own sense of common purpose had frequently foundered over the same issues. Nineteenth- and early- 20th-century Congregationalists lived with a keen awareness of the past’s significance. They disagreed about its meaning, not its import.

Bendroth suggests that contemporary mainline Protestants are more likely than their American evangelical counterparts to recognize that historical change is “messy and complicated and, in the end, ambiguous.” Mainline Protestants tend to celebrate the overcoming of past injustices, whereas evangelicals more often yearn for a mythical golden age of American Christianity. Yet as Bendroth observes in closing, few mainline Protestants pay attention to their ancestors any longer.

For most American Protestants, the pertinent question would be: What past? That of their denomination, to which they have little attachment? That of their individual church, in which their roots are far more shallow than those Geraldine Taylor had in her congregation? The premerger Congregationalists’ collective memory was trained on one small subset of the great cloud of witnesses that surrounds all followers of Jesus Christ. Most American Protestants, by contrast, are rootlessly adrift.