Afghan morass

The recent news out of Afghanistan has not been good: victories by the Taliban, a mistaken U.S. air strike against a Doctors Without Borders hospital, and reports of sexual abuse by Afghan military figures on U.S. military bases. For those with even limited experience in the country, such news is not surprising. Afghanistan is a country that has always defied attempts by outsiders to manage or control it, and outsiders seem nearly always to have acted unwisely.

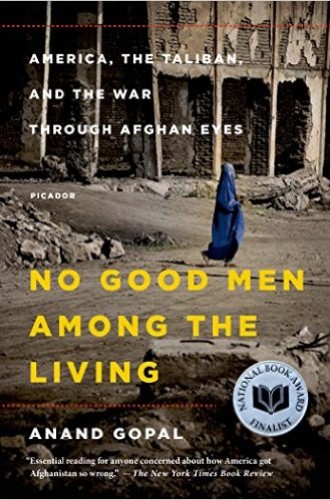

Anand Gopal knows this history well, and his reporting will stand out when historians recount “what went wrong” in Afghanistan. Gopal’s contribution is to see recent events through the eyes of Afghans themselves. In No Good Men Among the Living, recently released in paperback, the journalist does not spare Afghans responsibility for what has happened in the past 14 years. But he shows how Americans made a bad situation even worse.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Afghanistan has probably never been a “normal country,” Gopal argues. But since 9/11 and the arrival of American forces, Afghans have had reason to believe that what they have worked for could “vanish in a moment.” Gopal suggests that much of what has happened in Afghanistan might have been prevented with more foresight and pragmatism.

The world’s most powerful country was duped by politically savvy warlords who had played this kind of game before. During the 1979 Soviet invasion of the country and the ten-year occupation that followed, during the internecine wars after the Russians left, and during Taliban rule, Afghans survived “by calibrating themselves to power, the only sure bet in the frequent U-turns of Afghan history.”

America’s entry introduced a huge element of uncertainty along with massive amounts of cash and military power. The power of those two things together cannot be underestimated—but what a horrible, pernicious waste they now represent.

Of the nearly half a trillion dollars spent by the United States in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2011, only 5.4 percent went for development projects, such as improving water and food access or building better roads. “The rest was mostly military expenditure, a significant chunk of which ended up in the coffers of regional strongmen,” Gopal notes. With warlords “developing their own business and patronage relationships with the United States, the tottering government in Kabul had no choice but to enter the game itself. As a result, the state became criminalized, one of the most corrupt in the world, as thoroughly depraved as the warlords it sought to outflank.”

The book’s title stems from a Pashtun proverb which in this context means that the war “left no group, Afghan or foreign, with clean hands.” The warlord Hajji Zaman openly, even boastfully, admitted to his conniving. He told Gopal, “This whole land is filled with thieves and liars. This is what you Americans have made.” When asked to explain, Zaman said:

I went to the Americans and said, “I can find bin Laden.” I told them, “Give me $5 million and I’ll bring you his head.” So they went and talked to their bosses and arranged it, and I got $5 million. Then, a few days later, I went to al-Qaeda and told them, “Give me $1 million or I’ll turn you over to the Americans.” So they gave me $1 million, and I convinced the Americans to stop the bombing for a little while.

When Gopal asked Zaman if his intrigues would all eventually catch up with him, Zaman replied, “I have nothing to be ashamed of! I fought for my country. Only cowards and foreign agents have to fear. Not patriots. Not the people who survived all of these wars. We are true patriots.” Months later, Hajji Zaman was dead, the victim of a suicide bomber.

Another illuminating case is that of warlord Gul Agha Sherzai, who “followed the logic of the American presence to its obvious conclusion.” He and others “created enemies where there were none, exploiting the perverse incentive mechanism that the Americans—without even realizing it—had put into place. Sherzai’s enemies became Washington’s enemies, his battles its battles. His personal feuds and jealousies were repackaged as ‘counterterrorism,’ his business interests as Washington’s.” In short, “the Americans were not fighting a war on terror at all, they were simply targeting those who were part of the Sherzai and [Hamid] Karzai networks.”

The results were often horrific. Two attacks by U.S. forces in the province of Khas Uruzgan ended up killing nearly two dozen pro-American leaders and their followers. “Not one member of the Taliban or al-Qaeda was among the victims. Instead, in a single thirty-minute stretch the United States had managed to eradicate . . . potential (pro-US) governments, the core of any future anti-Taliban leadership—stalwarts who had outlasted the Russian invasion, the civil war, and the Taliban years but would not survive their own allies.”

Gopal adds: “People in Khas Uruzgan felt what Americans might if, in a single night, masked gunmen had wiped out the entire city council, mayor’s office, and police department of a small suburban town: shock, grief, and rage.” Incredibly, despite an admission by the Bush administration that the soldiers “had killed only pro-American civilians, seven soldiers in the attacks received a Bronze Star for valor.” And one master sergeant was even awarded a Silver Star.

The “moral morass,” as Gopal calls it, got worse because at “every step the United States may have been the hapless victim of Afghan strongmen, but it was also setting the rules of the game, and then following those rules through to their logical, bloody conclusions. The war on terror had become an end in itself, the ultimate self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Gopal reached this conclusion well before the dismaying and shocking revelations in September 2015 that the American military looked the other way when it came to Afghan military leaders sexually abusing boys, even on U.S. military bases. The revelations seem to have generated little concern in the United States.

Evoking the spirit of Franz Kafka, Gopal notes how absurd the war became. If you were aligned with one group and ended up as a prisoner of another at one of the many U.S. military outposts, in all likelihood you might face the following scenario:

The unit apprehending you might have a relationship with one strongman, for instance, while you worked for another strongman tied to a different wing of the US military or the CIA. In this way, hundreds of Afghans working for pro-American commanders wound up ensnared by one of the Coalition’s many tentacles. And once branded as a terrorist, no amount of evidence or good sense could save you.

Indeed, you might ultimately end up at Guantanamo—where further confusion and inefficiencies would take hold, the result being that “only a handful of Guantanamo’s Afghan inmates would turn out to be Taliban members of any import.”

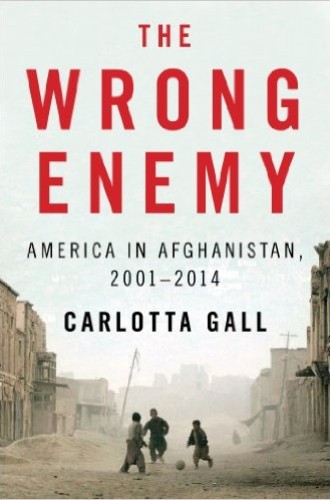

Carlotta Gall, correspondent for the New York Times, is no stranger to similar absurdities. The Wrong Enemy: America in Afghanistan, also just out in paperback, is penned in the venerable tradition of a Times reporter’s memoir, and so is different in tone and focus from Gopal’s. She argues that the real enemy of the United States was not in Afghanistan at all but in neighboring Pakistan, where al-Qaeda and the Taliban have been funded and trained.

Gall focuses on the dysfunctional relationship between the United States and Pakistan. She builds a strong case—though hardly a new one—for the claim that Pakistan security forces protected Osama bin Laden. At the same time, she notes that former Afghan president Hamid Karzai came to realize that the U.S.-led war against the Taliban was probably doomed because no U.S. administration would ever exert enough pressure on Pakistan to stop its support for the Taliban.

Karzai may have been right on that score, but he was hardly the person to champion change in Afghanistan. Described by underlings as a mercurial leader and a horrible administrator, Karzai, according to both supporters and those within the Afghan human rights community, allowed “some of the worst war criminals and mafia bosses access to power.”

Is there a way out of this morass? Gall worries that the United States has turned its back on Afghanistan because it tired of the effort and viewed its cause there as lost. As one former diplomat put it: “The war was essentially unwinnable; win, lose, or draw, Afghanistan was not worth the effort.”

Gall disagrees, calling militant Islamism “a juggernaut that cannot be turned off or turned away from.” The fallout from the U.S. pullout, she writes, is inspiring Islamists who liken it to the pullout of the Soviet Union.

Over the years, humanitarian activists have worried about what will happen when the United States leaves Afghanistan, and their worries intensified with the rise of ISIS. The implication of Gall’s book is that a withdrawal will embolden militant Islamism and bring doom. It seems that President Obama has the same concern—he recently announced that the United States will leave 5,500 troops in Afghanistan beyond the end of his presidency, a policy change he said was necessitated by gains by the Taliban and by the fact that “Afghan forces are still not as strong as they need to be.” He suggested that the Afghanistan war—already the longest in American history—will confront his successor. “I suspect we will continue to evaluate this going forward, as will the next president,” he said.

Another challenge for Obama’s successor will be the relationship with Pakistan. Gall chides Pakistan for its role in spreading “terrorism and fanaticism around the world” but also argues that the United States and its allies have “much work to do before leaving to bring Afghanistan and Pakistan into better shape to resist the tyranny of militant Islamism, or be responsible for even more blood and destruction.”

The problem, of course, is that the situation in Afghanistan is already violent. The idea of bringing Afghanistan and Pakistan “into better shape” does not align with recent events. The mistaken bombing of the Doctors Without Borders hospital, for example, only confirms worries that U.S. interventions do more harm than good.

Even Gall acknowledges that there is little to show for U.S. intervention in Afghanistan. The United States has “paid heavily in blood, treasure and prestige” since 2001. After a “trillion dollars spent . . . [and] tens of thousands of lives lost” the United States and its coalition partners will leave Afghanistan “in much the same predicament as it was when they arrived: a weak state, prey to the ambitions of its neighbors and extremist Islamists.”

One of Gopal’s essential points is that of the trillion dollars spent in Afghanistan in 14 years, only the barest amount has gone toward the things that Afghans really need—better roads, schools, and access to food. The real enemy in Afghanistan remains what it has been for years: the deadly, bitter, and lethal combination of poverty, neglect, and hopelessness. Many lives and resources have been wasted in not recognizing that fact.