One story, three ways

In 2014 the Islamic State destroyed the Mosul mosque in Iraq reputed to contain the tomb of the prophet Yunus, whom Christians know as Jonah. Some Westerners saw this act as a blow against any surviving vestige of Christianity in the region, but of course Jonah is also venerated by Jews and Muslims. Like many other patriarchs and prophets, he is part of the common heritage of all three faiths, although these figures are imagined differently.

Even when holy men and women are portrayed in sacred scriptures, the texts are subject to constant commentary and interpretation, which subtly or not so subtly changes the significance of the various characters. In turn, these fluid interpretations have a profound effect on popular belief and devotion, and commonly on artistic representations. Commentaries, then, are no mere appendices or optional extras, but rather an integral part of the wider story of faith, and of faiths.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The patristic scholar Robert C. Gregg illustrates the role of biblical interpretation by tracing five scriptural stories as they were later understood by Jewish, Christian, and Muslim commentators: the stories of Cain and Abel, Sarah and Hagar, Jonah, Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, and the Virgin Mary. Although any number of examples could have been chosen, this collection has the virtue of including three stories focused chiefly or substantially on female characters.

The volume’s subtitle is misleading, suggesting that the book covers interfaith interactions during the opening centuries of Islamic rule. Instead Gregg ranges widely, from the first century AD through the 16th, and he does not say much about true encounters. These are parallel retellings demonstrating how Jews thought about a topic, then Christians, then Muslims, without necessarily speaking to each other. These might be shared stories, but the amount of direct sharing is strictly limited.

With that limitation, the book offers some wonderful narratives that contain many insights—particularly for Christians. Plenty of Christian sermons have addressed Jonah’s farcical mission and his reluctance to be selected as a prophet. Jewish sages, in contrast, stressed his frustration at being sent to save a gentile city, and they expanded his mission for messianic and apocalyptic ends. In the end times, they held, Jonah would slay the Leviathan who had swallowed him and serve it to God’s faithful.

The story of Sarah and Hagar also offers surprises for those unfamiliar with the Qur’an. In Jewish and Christian memory, Sarah is the primary character, but the Meccan mythology focuses on the abandoned Hagar and her son, Ishmael. When pilgrims visit Mecca today, their ritual actions and travels reenact her experiences in the desert; for instance, they visit the spring where she found water to save herself and Ishmael from death by thirst.

Perhaps the greatest contrasts concern Mary. Christians may be startled when they learn that Mary is a major and beloved figure in the Qur’an and the early Muslim commentaries. She takes up considerably more space in the Islamic scripture than in the New Testament, with a lengthy backstory drawn largely from a Christian alternative gospel, the Protevangelium. Jewish authors also discussed her, but in extremely negative terms, as the mother of a deceptive pseudo-Messiah. In various stories, she was viewed as a slut who dallied with Roman soldiers or as the victim of an evil sorcerer who deceived an otherwise virtuous young woman. One particular antigospel discussing Mary, the Toledoth Yeshu, or Life of Jesus, was hugely popular in Jewish communities across medieval Europe. Martin Luther’s horror at reading this venomously anti-Christian tract did much to fuel his anti-Semitism.

Some of the most memorable stories come from commentaries on Joseph and the wife of the powerful Egyptian official Potiphar—the woman Muslims know as Zulaykha. Genesis 39 reports that the wife tried to seduce Joseph, and that when she failed, she falsely accused him of attempting to rape her.

In all three traditions, commentators discussed at length exactly what role Joseph had played and how far he had ventured into consensual sexual behavior. Had he been totally chaste and resisted all her blandishments? Or had he gone along to some extent, but then realized his danger at the last moment? In a late ancient world increasingly suspicious of sexuality, Christian fathers stressed Joseph’s total purity and the rigorous self-control that allowed him to escape unscathed. For Jewish sages, the scriptural story allowed otherwise puritanical scholars to discuss sexual problems and encounters in surprisingly frank detail. The religious context also allowed visual artists to address the story, almost always with an emphasis on the wife’s nudity. If the scene was biblical, how could it be condemned as soft porn, which it often was? Other scholars, of course, responded far more seriously. In one strand of Islamic tradition, mystics and Sufi poets wholly spiritualized Zulaykha’s lustful nature, presenting her as a symbol of the human soul yearning for God.

Readers might know the name Zulaykha from Max Beerbohm’s riotously funny 1911 novel Zuleika Dobson, about a flamboyant seductress in Edwardian Oxford, and it is not inappropriate to mention that comic treatment in this otherwise grim context. Islamic tradition makes “Potiphar’s wife” a much more interesting and rounded character than does the Bible, actually dignifying her with a name. Her husband, in contrast, is known only as al-Aziz, the “Powerful Guy.” The Qur’an adds a sequel in which Zulaykha summons her women friends to a banquet, at which all have knives to cut their fruit. When Joseph passes by, they are so overcome by sexual desire that they do not notice they are cutting into their own flesh. Later commentators debated over how many of the women unintentionally killed themselves in the process. You may make fun of me, Zulaykha tells her guests, but look at the temptations I have to deal with! I don’t think a scholarly work on comparative Bible interpretation should have me laughing quite as often as this one did, and by no means only in this section.

The Zulaykha tale should serve as a salutary reminder to Christians and Jews about the nature of the Qur’an. When Westerners open the Qur’an today, they are often investigating only what it says about justifying violence, the nature of jihad, or religious intolerance. All those themes are obviously critical, but it’s easy to lose sight of the book’s character as an assemblage of stories, legends, and folktales. Some of these verge on being shaggy dog tales, while others look like they have strayed from a story by Jorge Luis Borges. Consider, for instance, the mind-twisting Moses story in Sura 18. One of the pleasures of reading Gregg’s book is discovering the wide-ranging humanity and intelligence that runs through the early Islamic tradition, even when he discusses weighty scriptural matters.

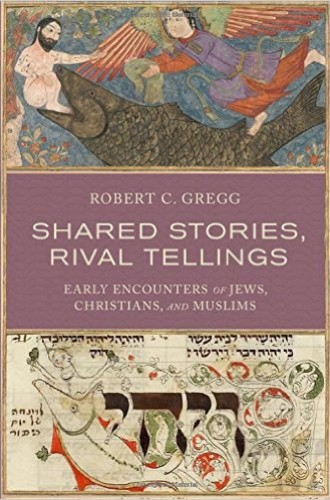

Another great virtue of Shared Stories, Rival Tellings is Gregg’s frequent use of visual depictions of the stories. Often these cast light on how the stories were evolving, and more particularly on how the underlying ideas were reaching the consciousness of ordinary believers.

Gregg’s book has much to recommend it, but it is not a straightforward read. Instead of bringing out the major themes that run through the various descriptions, the author works his way painstakingly through each story as it was treated in each religion. Such exhaustive, step-by-step scholarship can be hard going for a general reader. I wonder whether the book should have been structured differently. Each of the individual case studies runs to a hundred pages or so, with Mary taking up 140 pages. Each section might have made more sense as a freestanding short book or could have been expanded slightly into a fuller treatment. Are five books actually hiding in these sprawling pages?

But this is a valuable, scholarly work with an abundance of memorable, surprising stories that will provide new insights even for readers who think they know this material very well. It repays endless dipping.