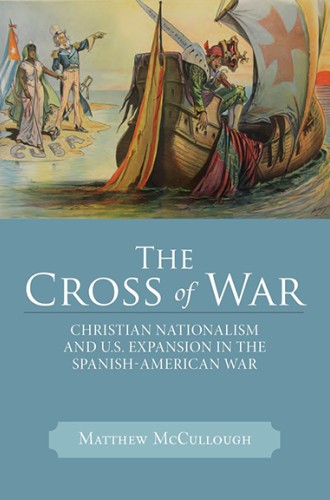

Baptizing empire

Harry S. Stout’s monumental history of religion and the Civil War, Upon the Altar of the Nation, has prompted other historians to write about the often vexed and complicated relationship between faith and warfare. Recent contributions to this long-neglected genre in American religious history include works by Thomas S. Kidd and James Byrd on the American Revolution, by Jonathan H. Ebel on World War I, and by Rick L. Nutt on Vietnam.

In this important contribution to the conversation, Matthew McCullough argues that the Spanish-American War signaled a crucial turning point in American self-understanding and self-justification. Although it was relatively brief in duration and occurred between two much larger conflicts, the Civil War and World War I, the Spanish-American War saw the emergence of what McCullough calls “messianic interventionism” to justify an increasingly imperial foreign policy. Religious leaders, he contends, played a crucial role in this transformation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

McCullough makes a persuasive case. Whereas the Civil War was inward looking and fought in order to resolve a domestic crisis, Woodrow Wilson defined the nation’s task in World War I in far more global terms: “making the world safe for democracy.” How did we move from A to B?

What McCullough describes as “an often forgotten little war” would seem an unlikely proving ground for messianic interventionism. From the mysterious destruction of the USS Maine in Havana’s harbor on February 15, 1898, to the Treaty of Paris, in which Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded to the United States, the Spanish-American War lasted only ten months. Although no casualties should be taken lightly, the toll of the war was relatively modest. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, 385 Americans died in battle in that war, compared with more than 53,000 in World War I; according to historian J. David Hacker’s recent estimate, perhaps 750,000 people died as a result of the Civil War.

By the end of the 19th century, McCullough argues, Americans were taking a keen interest in world affairs, partly because of robust missionary activity on the part of American Protestants. Although the perception—not unfounded—of Spanish misrule in Cuba might have predisposed religious leaders to action on humanitarian grounds, McCullough finds that they initially resisted calls for military action in response to the Maine disaster.

When President William McKinley declared war, however, these same leaders climbed aboard the bandwagon, initially framing their reason as “concern for oppressed humanity.” As the Christian Standard opined, any war “should be in behalf of the weak against the strong, to secure liberty for the down-trodden of the earth.”

Once aboard the bandwagon, Protestant ministers began spinning out theological justifications. The United States was both the Good Samaritan and the Crucified One. Henry Van Dyke of New York’s Brick Presbyterian Church declared that the heavy cross of war “must be carried in the same spirit in which Christ bore his Cross and fought his battle on Calvary.”

As the United States scored quick military victories, ministers began to ascribe their success to divine providence and the obvious superiority of American—that is, American Protestant—righteousness over the “barbarism” of Catholic Spain. Just as providence had sent favorable winds to help the British defeat the Spanish Armada in 1588, so too the Almighty had superintended American victories in the Spanish-American War, especially George Dewey’s rout of the Spanish fleet in Manila.

Soon, perhaps inevitably, rhetoric about American destiny emerged. The United States is “a Christian nation,” Methodist minister James King declared. The war with Spain was not primarily a military confrontation; it was a “contest in which the character of civilization and the interpretation of the Decalogue and the Sermon on the Mount are involved.”

How did Roman Catholics in the United States respond? In one of the book’s most fascinating passages, McCullough finds that the “Americanist” bishops, led by John Ireland, resolutely lined up with the American cause. “No true American Catholic,” Ireland declared, “will think of espousing the cause of Spain against that of this country because the former is a Catholic nation.”

Having rationalized the use of military force, the clergy turned their attention to a justification of imperialism. The United States itself had moved from adolescence to what one minister described as “a glorious manhood,” and so America, the font of liberty, had an obligation to pass liberty along to others. Indeed, the rhetoric of development and coming of age pervades the era. “We have come to our maturity and take our place as a power,” the United Presbyterian announced, “and we do so, not in the spirit of conquest or aggrandizement, but for humanity and right, for God and his truth.” In McCullough’s words, “a mature America led by the providence of God now embraced a responsibility to extend that freedom to others.”

Not everyone jumped at the U.S. offer of freedom, of course, as indicated by the Philippine-American War—and by not a few interventionist wars since then. Religious leaders cast the American annexation of Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines as a reluctant duty, a variation of the “white man’s burden,” necessary because the people there lacked the moral character to govern themselves.

It’s impossible to read The Cross of War without discerning the long rhetorical, theological, and ideological shadow that the Spanish-American War cast over successive American military engagements. When Wilson initiated a series of interventions in Latin America, for instance, particularly the Mexican Expedition of 1916, he explicitly invoked the precedent of the Spanish-American War. Further along, the parallels between McKinley’s statement that he “went down on my knees” for guidance and George W. Bush’s declaration that God told him “to go and end the tyranny in Iraq” are difficult to miss.

Although McCullough mentions 20th- and 21st-century wars, his analysis is not heavy-handed, and he wisely avoids the trap of presentism—he allows the reader to connect the dots. The Spanish-American War and successive rationalizations for both violence and imperialism have much to teach us about the malleability of theology to justify bellicosity.