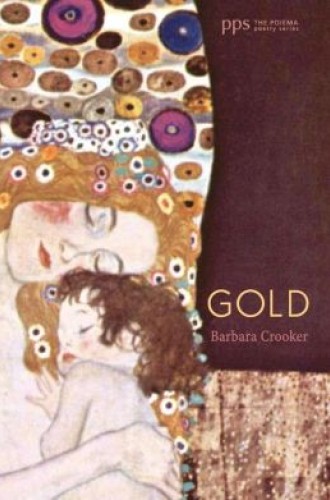

Gold, by Barbara Crooker

I find myself reading Gold at the height of October. Wind whips maple leaves and false sunflower petals into the sky, the colors as bold as fingerpaint. As the beauty intensifies, the sense of impending death—the first killing frost at the edge of all this autumn glory—intensifies as well. Having recently entered middle age, I feel like I’ve reached that edge myself. Wasn’t it summer just yesterday? But a muscle I pulled six weeks ago still hasn’t healed. I’m a bit more tired and ragged. And this year I tune into beauty more than ever before.

Barbara Crooker, a prolific, award-winning poet and teacher, writes in the throes of such beauty. Her books Radiance, Line Dance, and More resonate with the lushness of heightened senses. Known for her interest in ekphrastic work, Crooker enters the shades and brush strokes of daily life with such a reverence for the physicality of the world that readers want to take notice, live better, and, in the case of Gold, die better.

Gold begins with a series of lyric poems about autumn, lines afire with cornstalks and chrysanthemums, finches’ wings, stripteasing maples, and leaves going “presto chango, garnet / and gold.” Although Crooker makes it clear in these poems, sometimes painfully, that “nothing gold can stay,” she acknowledges nature’s victory, even on the brink of decay, over the world’s struggles with school shooters and a plummeting Dow Jones. But soon enough, Crooker foreshadows her own descent into grief in the poem “Late Prayer,” in which she wonders, “Will I be strong / enough to row across the ocean of loss / when my turn comes to take the oars?”