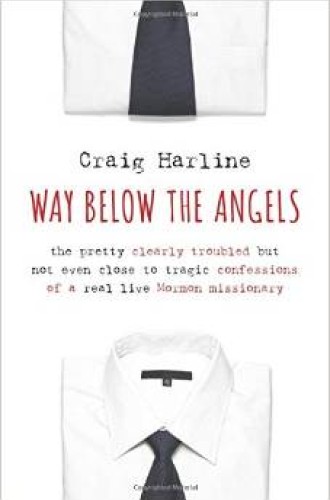

Way Below the Angels, by Craig Harline

One cold afternoon in 1975 in a small rented bedroom in Antwerp, the young Mormon missionary Craig Harline (Elder Harline in Mormon parlance) had a faith crisis—though it is not quite right to call it that. He was frustrated with his mission, dismayed at his failure to convert even a single soul after months of work in Belgium. His hope and even his faith in God were waning. Maybe he was fooling himself; maybe God didn’t care. Maybe there was no God.

To use the phrase “faith crisis” places young Elder Harline into a well-trodden narrative with guides familiar to most students of religion—Augustine, John of the Cross, even Malcolm X. There are the common wayposts—doubt, shattered confidence, surrender, catharsis. All of Christian history led to this moment: Elder Harline kneeling beside his hard bed, gazing toward heaven through his little window and the gray winter sky.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Yet Harline knew none of this, which is what makes this book so touching. He was no Augustine or Paul, no Billy Graham or Joseph Smith, not even, as he worried while in his initial weeks of training, a match for Elder Downing, the hero of his cadre of 19-year-old Mormons preparing to go out into the world and preach their gospel from the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and seven memorized lessons. He experienced the trials of faith as though he was the first and only, and the Harline of today—a historian of early modern Europe at Brigham Young University—is particularly gifted at capturing the universal humanity in what was an average experience as far as Mormon missions go.

As the title indicates, Harline’s mission was neither particularly heroic nor particularly tragic, Harline himself neither a prodigy nor a failure. He was only a young man not well versed in scripture—like most Mormons (and most Christians), largely ignorant of Christian history and theology and possessed of no preternatural faith or spiritual gifts. As he says, “I’d never had the classic crisis of faith over whether God existed, or even the classic Mormon crisis over whether the church was the True Church or not, because there hadn’t been any thought of such thoughts growing up.” Harline, this is to say, is a perfectly average Christian.

And that is gloriously enough. Many of the foibles Harline sees in his younger self will make many Mormons, ex-missionaries and not, nod in recognition, for mission culture is a highly potent distillation of Mormonism in total. Yet Harline is far less concerned with providing commentary on either Mormonism or its mission program than with capturing what it is like to be one of those young men in a white shirt and a tie who depart the safety of Utah’s Wasatch Front for such exotic locales as Belgium.

He struggled with perfectionism, “the highly popular missionary view that if you didn’t obey 100 percent of the rules 100 percent of the time, then you couldn’t be worthy of God reaching down and blessing you with converts.” He struggled with Roman Catholicism, convinced that all conversions derive from the influence of the Holy Ghost and therefore all rejections derive from the influence of Satan. Thus as Belgian after Belgian explained, “I am Catholic,” “I am Roman,” “I am Christian,” the young missionary began to shake his fist at every Catholic church he passed, cursing the priests for consorting with the Adversary. In jest. Sort of. He struggled with mission bureaucracy, hoping to climb the ladder from junior companion to senior companion to various arcane positions of accomplishment—district leader, zone leader, assistant to the president—through dutiful filling out of reports and wrestling with the printer in the mission president’s office.

All of this—the officiousness, the naïveté, the compulsiveness about checklists and rule following—will be familiar to Mormons, and they certainly are traits easily stereotyped by critics of the faith. But Harline realizes that such foibles are simply and inevitably human, and his account is loving, more sheepish about than critical of his own blindness and blunders and those of the missionaries around him. He and his fellow missionaries were and are deeply sincere, in a truly humane sense.

The Antwerp mission—like any Mormon mission—could be hard on shallow faith. Idealistic 19-year-olds, certain that God would open the way for them, ran headlong into ceaseless rejection; children making fun of their white shirts and ties and chanting “CIA! CIA!”; ploddingly endless rows of doors, most of which would not be opened. Hours, every day. Repeatedly Harline came close to converting somebody who abruptly reversed course, and on one occasion he baptized a woman who, after a few follow-up visits, stopped answering the door. It was devastating. And yet he persisted.

That grinding effort brought to Harline a particularly Mormon form of grace. Moments of grace did not number nearly as many as the rejections, but sometimes, wondrously, a kind, elderly couple like Raymond and Yvonne Aerts would invite the young men into their home and amiably decline to learn about Mormonism while feeding and befriending them nonetheless. Or he would find himself in a snow-covered field near Zichem, late on Christmas Eve, having come with three other missionaries, a “little band of local magi,” to deliver a plate of sweets to a lonely woman once baptized Mormon who no longer came to church. As he looked out over the dark, untouched snow around her home, he “was smitten, overcome by not only the sort of calm I’d felt in the dismal upstairs bedroom but an unexpected joy too—at seeing all this, at being in this place, in this land.” Protestants sometimes say that Mormons lack a language of grace, but the spiritual regeneration Harline experiences on his mission is rooted deep in Mormon lifeways, theology, and language.

“I want to tell them that we weren’t much different from any of them, even though we seemed like it,” Harline thinks, when he remembers all the Belgians he met. It sounds as though he is apologizing for his clumsy, youthful aggressiveness, and he is, but he is also thanking those Belgians who embraced him nonetheless. He is recalling the basic kindness that underlies the missionary impulse, whatever its execution, and he blesses Elder Downing, Elder Youngblood, Sister Acey, and all the rest for “their good hearts. Their missionary hearts. Their Belgian missionary hearts. Which are maybe just empathetic hearts.”

The rhetoric of family that dominates so much of Mormonism today derives from the essential vision of Joseph Smith: that salvation is a communal task, that sacraments are meant to bind together families and congregations and communities, and that heaven is heaven only because it is shared by those you love. Harline’s faith crisis and its resolution, his time in Belgium, and the great insight of this memoir are not merely an affirmation of the truth of Mormonism. They are a gradual, growing affirmation of one of those truths: that we all need simply to love and to be loved.