Following Martin

What happened to the civil rights movement of the late 1950s and the 1960s? The question comes up among historians and interested observers who find it hard to trace a narrative line from the heady days of Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma through the cultural free-for-all that followed. What are the “assured results” of those sacrifices? Increasingly, the question is framed in the ever-expanding shadow of Martin Luther King Jr., whose persona has evolved from the wire-tapped radical of the 1960s to the treasured martyr whose memorial rests beside those of Jefferson, Lincoln, and FDR in the nation’s capital.

With his memorial and a national holiday in his honor, King takes his place in the nation’s book of founding fathers and heroes, his story interleaved with theirs. Most schoolchildren are familiar with his epochal achievements, including his many campaigns, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the tragic circumstances of his martyrdom. But what is the after-story? Were the accomplishments of his generation only a dream? Or did they inaugurate a new and very different struggle for civil rights in America?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

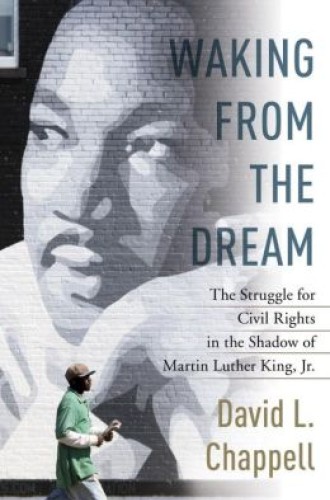

David Chappell takes on the question. Chappell, who teaches at the University of Oklahoma, is the author of an earlier book on King, the highly respected A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow. Chappell combines two remarkable strengths in a historian. First, he is an excellent storyteller with the ability to translate the personalities and political intrigues of another generation into narratives that still matter.

For example, when he reviews the stories of Coretta Scott King and Jesse Jackson, he manages to view them through a double lens. Up close, they are real people and not the caricatures with which we have become familiar. Of Coretta King he writes, “Her pieta-like irreproachability seemed to grow even as her husband’s flaws were exposed over the years. Nobody, after all, had borne those flaws—and the vulnerability they translated into—more directly or more intimately than she. . . . It would have shocked her husband to learn that his memory had become a political asset. But it was becoming a great one, and so quickly that she had little choice but to make his memory the center of her public career.”

The historian’s second lens is the high-angle shot. Chappell views his subjects as actors whose performances stimulate a response and actually do something on the political stage. With regard to Jesse Jackson, the author reminds us of the complexity of the man, whose uncompromising assault on racism coexisted with an equally uncompromising opposition to abortion. Chappell skillfully portrays Jackson’s character flaws as well as his stunning political successes—in 1988 he won the Democratic primary in Michigan with 55 per cent of the vote, and ten other states as well. In four years his voter registration campaigns added 2 million new black voters to the rolls. His diplomatic achievements made headlines.

Chappell’s second strength lies in his attention to the backstory. It is painstaking. Some of the best reading is found in his voluminous endnotes. If the reader wishes to retrace the controversy over Jesse Jackson’s self-aggrandizing posture immediately after King’s assassination, it is all there in the notes. (By the way, Chappell convincingly shows that Jackson’s bloodstained claim to have cradled the dying King in his arms was a myth, the result of a press rumor gone viral in its day.) If one has forgotten the political shenanigans that preceded the enactment of the King holiday, they are all here in this book, including the spectacle of Republican opponents caving to the new black demographic in America, leaving the racist Jesse Helms to twist slowly in the wind. Or, if one has forgotten liberals’ over-the-top denunciation of Ralph David Abernathy for telling secrets everybody already knew, Chappell provides the sad details.

The years that followed King’s assassination were, in Chappell’s words, “full of ferment and vital experimentation in civil rights.” That his book consists of a series of episodes only highlights the difficulty of identifying anything resembling a post-King narrative of civil rights in America. Of these episodes, which are significant and which are peripheral to the continuing story of civil rights? The most important of these is the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act. The landmark laws of 1964 and 1965 were inspired by Birmingham and Selma, but they left residential segregation largely untouched. The power of real estate played, and continues to play, a huge role in restricting economic and educational opportunities. King’s death made it possible for the Johnson administration to push through legislation that eventually affected nearly 100 percent of housing transactions nationwide, and it did so with broad Republican cooperation. It was the last of King’s victories in America.

In the early 1970s black leaders were forced to come to terms with the absence of a charismatic leader. The trend away from King’s classic (and Christian) organization toward a variety of black nationalist strategies was already a fact of life in his final years; his death underscored the dilemma. The response came in efforts to build black institutions rather than anoint a black leader. The National Black Political Convention was held in 1972, and the Congressional Black Caucus was founded the year before. At the caucus’s founding the actor Ossie Davis brought down the house with, “It’s not the rap, it’s the map; it’s not the man, it’s the plan.” The result was the emergence of not one but a cadre of gifted black politicians, such as Richard Hatcher, Carl Stokes, Coleman Young, Maynard Jackson, Tom Bradley, and Shirley Chisholm, whose allegiance to established political parties effectively distanced them from more incendiary options. Black political conventions attracted participants in unprecedented numbers—accompanied by the predictable conflicts and fractures, leading Chappell to conclude, “The quest that animated the conventions yielded no tangible new achievements, no new map or plan.”

Chappell then turns to the personalities who, either self-consciously or unintentionally, assumed prominence in the years after King. These included Ralph Abernathy, Jesse Jackson, and Coretta Scott King. In contrast to the men, Coretta King’s style of leadership was often restrained and veiled; yet in the steadfastness with which she pursued a legal holiday for her husband it proved no less effective than Jackson’s more spectacular methods.

The later chapters in Waking from the Dream reflect fewer legislative initiatives and more affective expressions of King’s influence on American life. The book roughly covers the years 1968–1990; in those years King’s legacy was chiefly symbolized by the establishment of the Martin Luther King holiday. Chappell’s account stops with the political maneuvers that made it possible. One would like to hear more about the aftermath of the holiday and the many ways, great and small, in which remembering Martin Luther King has fostered a spirit of service and subtly refigured the texture of American life. But one book can’t do everything.

It’s more difficult to trace a meaningful connection between the end of the King era and the oft-told stories of King’s extramarital affairs and his plagiarism, which Chappell treats in some detail. While they created hotspots of media attention, they failed to cancel out the courage, tenacity, eloquence, selflessness, and other virtues that helped make the movement possible. How the scandals affected King’s reception by the public or bore any influence on subsequent struggles for civil rights seems impossible to document. One can only hazard an educated guess that rumors of King’s personal failings created an excuse for conservative Christian groups to withhold their blessing. Chappell reaches no conclusion other than to note that King’s standing as “one of the greatest idealists of all time” remains undiminished.

If one is looking for an omission in this survey of the post-King years, it is the deafening silence of the religious voice. In Chappell’s history of 1968–1990, the importance of religion does not come up on a single page. This is surprising since Chappell’s earlier book portrayed King and his opponents in theological terms. And it is even more surprising when one remembers that King consistently presented himself and his movement in extravagantly Christian imagery. In Memphis the night before he died, he interpreted his mission through the lens of the Good Samaritan and Moses on Mount Nebo. On a scale unprecedented in American history, King transported the Judeo-Christian themes of suffering, redemption, justice, and hope from the safety of the canopied pulpit into the streets and cities of the nation. He dreamed a social revolution in the mirror of the Bible and the gospel.

Thus it does not seem unreasonable to ask if there is a story to be told of religion “after King.” If so, it would certainly proceed in fits and starts, in disjunction from King’s magisterial synthesis of Protestant liberalism and black church religion. It would tell of the growing militancy among black Christian leaders who grew weary of the theology of nonviolence and distrustful of the preachers who delivered it.

Later, that distrust would focus on the men who assumed ownership of the revolution. Other questions come up: In the Me Decades of the 1970s and ’80s, was it a reaction to King’s social gospel that helped fuel the charismatic movement, therapeutic religion, and the quest for self-realization? What are we to make of the resurgence of evangelicalism and its current embrace of Martin Luther King as a soul mate? And in the academy, how are we to understand black religion’s move away from the black church?

In ever-shifting scenarios, the story of King’s dream persisted beyond the life of the dreamer. As Chappell says, King began a work that “brought masses together in political and economic action to alleviate large-scale injustice and human suffering.” In fact, it inspired so many lines of growth they could not be contained in a single narrative or a single book. In the last year of his life, King’s message found a new hearing in the antiwar movement. It was succeeded by the Poor People’s Campaign, the women’s movement, the farmworkers’ struggle, environmental activism, gay and lesbian liberation, and other quests for freedom. In content and method, none of these initiatives replicated the civil rights movement of 1955–1968. But in spirit they all borrowed a burning coal or two from King’s synthesis of prophetic critique and prophetic hope.

Internationally, the same spirit brooded over other freedom movements. They sang “We Shall Overcome” in Leipzig, East Berlin, Prague, Tiananmen Square, Soweto Township, and countless other cities and towns. In these places they did not so much wake from the dream as embrace it and make it their own.

Today, numerical gains in black elected officials, already evident in the late 1960s, have overlapped the realms of business, academia, and the professions beyond anything King could have imagined. The losses, too, among the urban poor, the young, and the very old would have surpassed his powers of imagination. The realities of friendship and cooperation among the races can be seen in every neighborhood, community, and school. They are balanced out, but not canceled out, by harsh economic numbers, entrenched patterns of segregation, and violent eruptions of race hate in America.

Like a good historian, Chappell eschews a grand summation of all he has mined from the two and a half decades after King’s death. Congressman John Lewis is less reserved. On what would have been King’s 80th birthday, Lewis told a visitor to his Capitol Hill office, “Barack Obama is what comes at the end of that bridge in Selma.” That is matter for another book. In the meantime, we have Chappell’s carefully wrought study of a nation’s fitful waking from a beautiful dream. It seems to ask, Were we ever ready for a dream that big?