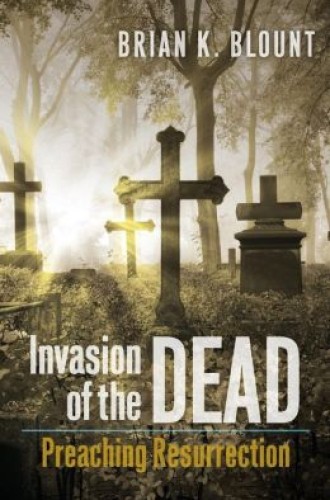

Invasion of the Dead, by Brian K. Blount

In this small book originating from his 2011 Beecher Lectures at Yale, Brian Blount mounts a sweeping, lively, beguiling, and convincing plea for recognition of and bold preaching about the God who, in Jesus Christ, invades and routs death, excites the “walking dead” and thus provokes “the dawning of the dead.” Resurrection, Blount argues, transforms all of us “living dead” into witnesses that God has plans for our morbidity and that God will not rest until those plans are fulfilled.

“Dead is a relative term,” says Blount. We are in a time of the “walking dead”: zombies are among us. It’s a grotesque world in which “humans and monsters often become hard to distinguish.” With genocide, mass murder, school shootings, and, for mainline Christians, the death of our beloved denominations and the diminishment of our churches, death has become “the new normal.”

In this moribund age Blount invites us to embrace the apocalyptic imagery streaming from popular culture. He considers the proliferation of living-dead TV shows and novels an opportunity for Christian preachers to think themselves back into a fresh affirmation of apocalypticism, and he enlists the testimony of Revelation, Paul, and Mark’s Gospel to show that the resurrection of Jesus is the initial and decisive divine act of apocalyptic re-creation and victory.