Poetry

Incarnadine, by Mary Szybist. This is a luminescent collection of poems, many describing Mary and the Annunciation from enticingly odd and original angles: from the point of view of the grass under Mary’s knees, from the point of view of Gabriel descending from heaven, from the point of view of girls assembling a puzzle of Mary, the queen of heaven: “this piece of her / neck could fit into the light part / of the sky.” The Annunciation finds its metaphors among the rare and the beautiful, such as a blue butterfly sipping on lupine. Here also are poems about various Marys, especially one who “tells herself that if only she could have a child she could carry around like an extra lung, the emptiness inside her would stop gnawing.”

Whose Saints We Are, by David Craig. This small press has published 20 titles since 2005, among them several volumes of the finest poetry of faith published in the past decade. Craig’s latest collection is no exception. It contains poems on subjects familiar throughout the Christian world (St. Thérèse, the Psalms, the Gospel of Matthew) and on subjects probably most familiar to Roman Catholics (Peter Maurin, Anna Maria Taigi, St. Alphonsus Liguori). Craig’s is a compelling voice, and he is skilled at both formal and free verse. Most notable, however, are the fierce lyricism of these poems, their strong narrative pull and Craig’s gift for drawing characters in bold strokes.

Gold, by Barbara Crooker. This collection begins with the autumn gold that presages loss and leads directly into softly wrenching poems about cancer spreading like dandelions, about the poet’s dying mother and about the turn of seasons as relentless as grief and the “unmothering” that ensues. A book to read cover to cover in one sitting, it will break your heart and then bring you to a new season. As its epigraph claims, “Nothing gold can stay,” but gold does come round again, pain turning to praise.

Waking My Mother, by Angela Alaimo O’Donnell. Here is yet another fine collection of poems about the loss of a mother, this time a mother difficult to love. “We loved her as we clamored to get out,” O’Donnell writes. The longing for connection, the shadow-guilt of being a “faithless daughter,” the memories of the mother’s “insult, injury, of unkind words” permeate these poems, and yet the poet has the urge to “bless my blesséd mother yet again.” Sheer craft wins the day in a stunning, devastating crown of sonnets, in poems like “Watching Dirty Dancing with My Mother” and in three short Dickinsonesque stanzas about “De-mentia.”

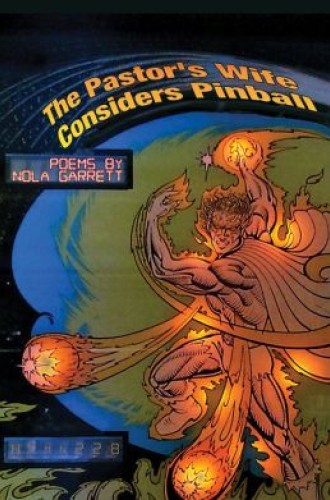

The Pastor’s Wife Considers Pinball, by Nola Garrett. In these engaging poems the pastor’s wife escapes committee meetings to enter a pinball parlor, where she patiently waits her turn. She then plays pinball with fervor and greed, attached to the flashing insides of things mechanical like the clockmaker, who unlike his prototype, sets it all in motion and then still appears on certain Sunday afternoons to adjust and tinker. Garrett’s persona struggles with God, with her desired versus proper role, with the way the holy is infused with all that is ordinary—for example, receiving communion from her husband: “He is opaque, / no flicker of remembering / his body searching mine last night /. . . All is now.” These are highly imaginative, delightful poems, and like all good ones they are slightly unsettling.