Health and wealth

Riches were not always beyond reproach. The Puritans famously convicted Boston merchant Robert Keayne of “oppression,” having determined that he was charging too many shillings for a bag of nails. Such hard-line censure was always rare, but even two centuries later, at the dawn of what Mark Twain dubbed the Gilded Age, New Testament warnings about wealth continued to generate compunction. When Cornelius Vanderbilt, the 19th century’s richest American, died in 1877, many fretted about the fate of his soul—as had Vanderbilt himself, according to some reports.

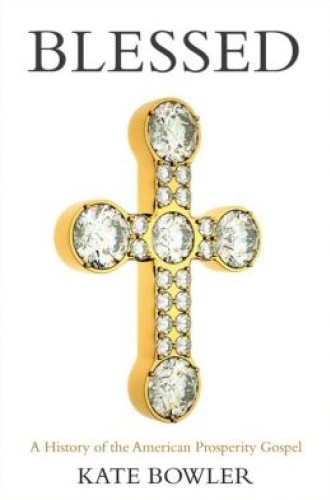

One of the most remarkable developments in the ensuing history of American Christianity is that money shed its moral ambiguity. By the mid-20th century most believers saw no contradiction between sincere faith on the one hand and upward mobility and unfettered consumption on the other. What is even more striking, as Kate Bowler shows in this marvelous book, is that millions came to see not just wealth but also health as a birthright of the born again.

The prosperity gospel eludes easy definition, so Bowler takes a multifaceted approach. Blessed is part genealogy. She traces the movement’s roots back to the turn of the 20th century, when evangelical and especially Pentecostal streams of faith intermingled with New Thought, a movement that emphasized the power of the mind to rearrange matter and taught that humans shared in the divine ability to create.