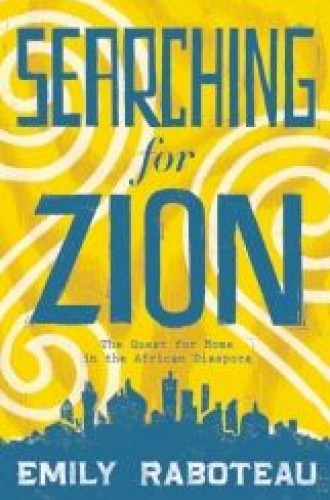

Promised lands

Partly a travel memoir, partly the spiritual journey of someone who claims no particular spirituality, and partly a family story of fear and joy, Searching for Zion follows Emily Raboteau’s imaginative religious adventures. She travels to “rabidly Christian” Ghana, where one business advertises itself as “Try Jesus Digital Photo Center,” and visits the smoke-filled dens of Jamaican Rastafarians, where they regard the queen of England as the “Whore of Babylon” foretold in Revelation.

The book is poignant, moving and often hilarious in its bitter honesty. Raboteau builds on centuries of African-American travel narratives and wraps her narrative around global searches for Zion. The result is both jarring and inspiring. Searching for Zion is one of those rare books that shines light not only on a personal exploration of faith but on the wider fabrics of faith in the modern world.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Raboteau begins at Newark Airport and ends in Katrina-ravaged New Orleans. One of her stops in between is Israel, where she visits her closest friend during adolescence. As teenagers, she and Tamar Cohen felt

themselves to be outsiders in white, Protestant, middle-class New Jersey. Raboteau is the daughter of a white woman and a black man and was raised Catholic. Cohen is Jewish and at one point in the early 1990s announced to her biracial friend, “I am not white.” Before they met up in Jerusalem in their early twenties, Raboteau was verbally and physically assaulted by security guards. Raboteau recalls never feeling “more black” than when she was mistaken for “an Arab.”

In Israel, Raboteau recognizes a theme that becomes central in her book: as one group creates and maintains their Promised Land, they simultaneously make it into a land of bondage for others. In Jamaica, for instance, Raboteau was entranced by Rastafarian members of the Twelve Tribes. Any group that was good enough for Bob Marley, she reasoned, was perhaps good enough for her. Their wordplay fascinated her. They are not “Jew-ish,” but “Jews.” They never underscore anything, but “overscore” all things. Their linguistic manipulation, however, did not offset their explicit and implicit homophobia. Raboteau could not fathom how individuals so attuned to group oppression and its effects on spiritual life could be so harsh toward gay people. She left Jamaica still in love with Marley’s music, but not so sure about his religious compatriots.

In Ghana, Raboteau chatted with African-American expatriates and ran into a clothing seller at Jesus Is Alive Fabrics. In Atlanta she almost fell under the spell of prosperity gospel televangelist Creflo Dollar. From there she went to Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, where in 1963 white terrorists killed four little girls by bombing the church. She ended her travels in New Orleans, “our Africa, our Israel . . . also our Egypt, our Dixie, our black bottom.” At each stop, Raboteau witnessed people who sought or continue to seek Zion. But she could never find true community with them.

A novelist, essayist and teacher of creative writing at City College of New York in Harlem, Raboteau is an exquisite storyteller. She is also the daughter of acclaimed religious historian Albert Raboteau of Princeton University. More than 30 years ago, the senior Raboteau wrote Slave Religion, a pathbreaking work of scholarship that examines how millions of West Africans fashioned new religious faiths and communities amid enslavement: from death they made deities; from sorrow they crafted new spiritualities.

Emily Raboteau’s book pays homage to her father’s work and to the “many thousands gone” that he honored as a historian. She illuminates what it is to live in a world made in part by the people her father studied. We have the good fortune to eavesdrop on their relationship, one marked by tender moments when the father dotes on his daughter, by didactic lessons when the teacher pushes his student and by tear-inducing tales of her father’s illness.

Raboteau’s spiritual travel memoir is not overtly political, although she has points to make about Barack Obama as he is perceived in the United States and throughout the world. She is a little hard on religious traditions she does not understand; for example, she writes about a Creflo Dollar rally that the “spirit moved like an airborne virus.”

But Raboteau does so many things well. She draws us into the story of her confusions and the confusions she causes for others. She inspires us with her hopes for Zion and even with her disappointments. She leads us to care for a cabdriver’s religious ruminations and about the Louisiana resident who after Hurricane Katrina explains, “Everyone else might forget us, but not God.” Raboteau shows us once again that searching for Zion may be more important than finding it.