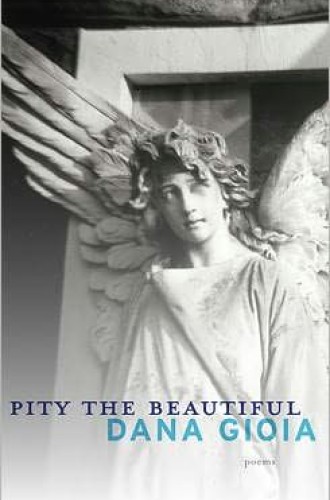

Pity the Beautiful, by Dana Gioia

Poet and critic Dana Gioia, former chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, signals his ambitious artistic tendencies and his firm spiritual commitments from the first poem of this new collection. A versatile poet, he works through traditional, inherited forms as well as through the free verse characteristic of the work of many of his contemporaries. A devout Catholic, he maintains a Catholic perspective of humility within a larger community and an appreciation of metaphysical mystery beyond surface impressions. A sacramental poet, he finds art in selected objects and in the heartbreaks that regularly come upon human beings.

In the first poem, “The Present,” rhymed according to a medieval Italian convention, an unopened gift lies on a bedside table. The reader perceives the beautifully wrapped present as an object of affection or at least of human connection. Whatever reserve keeps the present unopened—it could be sadness, regret, grief, bitterness or something else—the situation shows a restraint not unlike that experienced in the ritual patterns of worship. The careful packaging, like movement and order in liturgy, is appreciated and valued even though the content within is the essential object of delight and speculation. We pay a dear price when we abandon the forms of liturgy and poetry that wrap gifts of grace.

Just as Gioia works hard to breathe new life into old forms of poetry, he calls Catholic writers to work through the faith and life of the church to revive its music, art, architecture and liturgy and to enrich the greater culture, in the lineage of Dante, Michelangelo, El Greco, Graham Greene and Flannery O’Connor. In a 2011 address at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., Gioia called Catholic artists and writers to