An American original

When Mormon missionary James Brown carried his message to the frontier in the 1850s, he found a tribe of Shoshone Indians willing to listen. They had heard about Jesus before, but never about this new book Brown had brought. He told them of a distant and now dead prophet who had been given the Book of Mormon. Brown passed it around so tribal members could see it and turn the pages. The young men of the tribe balked. They grumbled that this was another fantasy of the white man. But then, as Brown recalled in his memoir, Chief Washakie silenced them. He picked up a Colt revolver and held it before the group. “The white man can make this,” Washakie instructed, and it proved that “the face of the Father is towards him.” The Shoshone should take the Book of Mormon seriously, the chief concluded, because they took guns seriously.

The Book of Mormon did not always need power to become prominent. It was a fascination even before it was first published in 1830. Unearthed (or invented—whichever word you please) in upstate New York by the young Joseph Smith, it became the founding document of the new Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It traveled far and wide with missionaries like James Brown, hopping from place to place as the Mormons fled from frontier to frontier until the bulk of them settled in the Great Basin of Utah. It went through revisions, illustrations, translations and even a new subtitle as the LDS church grew throughout the world. And now, with the ascendance of Mitt Romney in the Republican Party, the power of the LDS in conservative politics and the jokes of the animated sitcom South Park’s creators, the Book of Mormon is a work every American should take seriously.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It has become fashionable in recent years to narrate the lives of books. Without doubt, books have histories, and some books—such as the King James Bible, Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Mao’s Little Red Book—have had the power to make history.

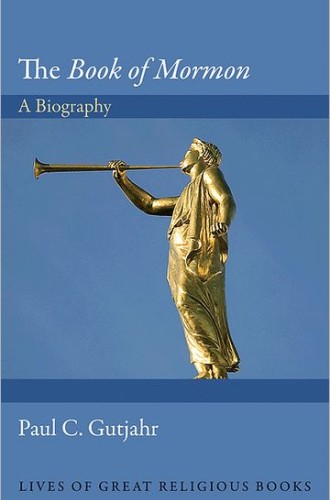

Historian Paul Gutjahr offers a brief and readable account of the Book of Mormon’s history. He highlights the origins of the book (at least the verifiable origins) and tells how Joseph Smith translated from golden plates the ancient stories of Middle Eastern Jews who trekked to the Americas thousands of years before Columbus sailed—who established civilizations, killed one another, prophesied the coming of Christ and eventually touched his crucified skin in the days following his resurrection in Israel.

Gutjahr follows the book through global missionary work and the process of translation (which usually takes 4.8 years). He discusses debates over the veracity of its stories and the locations of the ancient Jews-in-America. And Gutjahr shows how the LDS has presented the book: in illustrated versions, on the silver screen and in ostentatious pageants.

Readers who want to know what the Book of Mormon is about should read it. I recommend the Penguin edition of the 1840 revision because it resembles a novel without the chapter and verse markings, and because of the fantastic introduction by Laurie Maffly-Kipp. Be forewarned, though. Mark Twain called the Book of Mormon “chloroform in print.” He claimed that the real miracle was not that an angel visited young Joseph but that the new prophet could stay awake as he translated the writing. For nonbelievers, Twain may be right.

Gutjahr’s book is part of an effervescence of Mormon scholarship, for which we have more than Mitt Romney and LDS opposition to same-sex marriage to thank. Decades ago there was only a handful of scholars on Mormonism whom readers could trust, most notably Jan Shipps and Richard Bushman. In the 1990s, John Brooke’s The Refiner’s Fire and Terryl Givens’s The Viper on the Hearth showed that there are fascinating elements in Mormon cosmology and within the cultures of anti-Mormonism. Sarah Barringer Gordon and Kathleen Flake then outlined the important role of Mormonism in American politics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Now there is a wave of significant work. Patrick Mason’s book on Mormonism in the American South reveals just how belligerent anti-Mormonism was after the Civil War and how it galvanized American politics; Matthew Bowman’s The Mormon People is an expansive history that runs from the early 19th century to the present; and Joanna Brooks’s online writings and her memoir The Book of Mormon Girl narrate what it was like to live within the LDS in the 1970s and 1980s and what it is like now to defend a faith whose church hierarchy she finds so troubling. This fall books by J. Spencer Fluhman and John Turner will respectively recast the tales of anti-Mormonism and the rise of Brigham Young. It is an exciting time to think critically about Mormonism, and Gutjahr is one of the folks we can thank for providing some directions.

Those who want to taste only little morsels about the Book of Mormon will find many of their cravings satisfied by Gutjahr’s slim volume. They will encounter one Mormon artist who grew out his hair and beard so he could be the model for his own paintings. They will learn when the Book of Mormon received its subtitle, Another Testament of Jesus Christ (much more recently than one might suppose). They will even find that the renowned author of the fantasy story Ender’s Game, Orson Scott Card, is also the author of the most recent script for the LDS pageant about the Book of Mormon. These fascinating glimpses into the history of the book whet the reader’s appetite for more.

Gutjahr has dug up a number of first-rate artifacts that beg for more rigorous excavation of the terrain. For instance, when discussing illustrations of the Book of Mormon, he mentions that LDS leadership prefers the artwork to be hypermasculine. One wonders why the LDS would insist on this, given the tendency for religion in the United States to be dominated by women and often to be feminized in the visual arts. Gutjahr also has little to say about anti-Mormon uses of the Book of Mormon, except when he writes of those who in the early years of the movement tried to discredit it. To follow Gutjahr’s lead, one could examine whether and how Catholic and Protestant approaches to the book have changed over time, and how conservative Mormons, Protestants and Catholics regard the Book of Mormon today as they unite politically.

A historian’s tools don’t allow for conclusions to be drawn about whether the Book of Mormon’s tales are true or false. I am unable to peek back in time to upstate New York in 1830 and see what Joseph saw as he peered into the darkness. But it is apparent to me that anyone who wants to understand the history of the Book of Mormon quickly and easily should turn to Gutjahr’s volume. Gutjahr proved to me that reading the history of the book is just as interesting, if not more so, than reading the history recounted within the Book of Mormon itself.