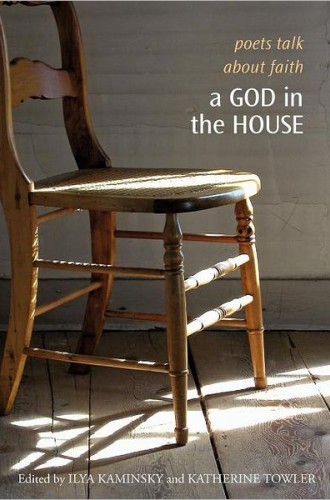

A God in the House, edited by Ilya Kaminsky and Katherine Towler

A striking and apt image enhances the cover of this new collection of interviews with 19 leading American poets. An antique chair sits half in shadow; its cane seat, crossed by a beam of light, filters bright intricacies onto the legs, the dowels, the timbered floor. The message here is illumination, from a source offstage. Against the dark wall behind the chair, the printed title, A God in the House, invites the reader into the mysteries of prosody and its sources.

I read this book end to end, pausing briefly between chapters. The interviews were conducted by Ilya Kaminsky and Katherine Towler either in person or by correspondence, and the poets’ responses take the form of frank personal essays. From diverse backgrounds and religious or nonreligious perspectives, the stories represent a spectrum of reflections about the sources of poetry and art. Most of the poets take for truth the idea that physical realities hold meaning beyond themselves that may be accessed and celebrated through poetry. Many of those interviewed are activists against injustice, violence, poverty or abuse, and some of their activism is religious. It seems as if outrage initially propelled them into pondering how the world works, or doesn’t, and into considering whether the traditional Christian view of a Creator God gives them cause for hope or reason for revolt.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I value discovering what poets have to say in prose as they find language to describe where they’ve come from, who they are, and how they catch a feather of experience and the emotion it carries and craft it into poetry. A common theme is the search for that indescribable place between belief and longing—guessed at or searched for and barely grasped.

This is the stuff of mystery, and many of these writers present themselves as mystics. Carolyn Forche says she finds no distance between the I and the Thou. Kazim Ali suggests that religious belief is not like a boulder to sit on but is “much more fluid.” Grace Paley exclaims, “We live in mystery, and the making of the world is simply great and mysterious.”

Poets tend to write as a way to search for the source of their images, as if their verses are floating a ladder through space between the visible and the unseen, hovering and ephemeral. G. C. Waldrep compares a poem to an ark, “a vessel that carries a message across a void.” Gregory Orr asks: “What was the original impetus to most poems? . . . As is true for most poets . . . this is usually a phrase. We call it ‘the given.’” Each of these essays is a witness to the validity of the receiving of the gift.

Creativity itself may be an attempt to harness spirituality. For some, Christian orthodoxy is seen as death to spirituality and poetry; they resolve the problem by replacing the deity with the self. Their writing often becomes a searching out of the self in order to express it. For others, such as Waldrep, Orr, Christian Wiman and Li-Young Lee, and to some extent Jean Valentine, Marilyn Nelson and Fanny Howe, Christianity is a valued source of illumination and connection with the invisible real. Forche doesn’t “attempt to resolve contradictions between spheres of faith and belief, considering all descriptions of deity as figurative.”

Disparate and idiosyncratic as these poets and their observations are, I hear echoes resounding among them. Most of them attempt to describe how art and spirit intertwine and integrate mysteriously, testifying that human language, with all its richness, is inadequate to catch and pin down transcendence; it is too fleeting, but that doesn’t prevent their ardent attempts. I was not surprised at how many of them have looked to exemplars such as Simone Weil, Thomas Merton and Emily Dickinson, each of whom were strugglers with human-divine mysteries, conscious of the divide and longing for integration. “The spiritual is in the palpable, physical world around us,” and “it’s the task of language and imagination to unveil the spiritual,” says Orr.

For some of the women poets, the power of being female has been a part of their spirituality and art. The concept of Shekinah, a word suggesting a resting place where God’s glory can dwell on earth, is found in both biblical and Islamic texts and is mentioned as a female presence by Eleanor Wilner. For her, Shekinah is the essentially feminine aspect of God. In my own mind and experience, I connect this concept with the action of the Holy Spirit (the member of the Trinity sent to “lead us into truth”) in activating the birth of a poetic image or idea. “God fills us as a woman fills a pitcher,” according to Jean Valentine. Fanny Howe tells us: “The wind is what I believe in, / the One that moves around each form.”

The necessity of attentiveness and awareness is a repeated theme—they are considered vital to the receiving of poetry. Li-Young Lee tells us: “As I’m walking around in the world, I’m noticing what is around me.” Jane Hirshfield, a practicing Buddhist, experiences “calling oneself into complete attention” and the sense that “awareness is the tiller” that guides her boat. Paul Celan says, “Attentiveness is the prayer of the human soul.” And Simone Weil: “Absolute unmixed attention is prayer.”

A sense of givenness is also regularly attested to in these pages. Waldrep tells us, “A few words came to me . . . later a few more words came . . . and then a few more.” Wiman speaks of “the visitations of poetry.” And Orr: “The first time I wrote a poem I knew this was it” and “The poems started saying themselves to me. And I wrote them down.” Wilner speaks of needing to “get out of the way in order to . . . take the work on its own terms.”

I have read many of these poets’ works, have met some of them personally and have heard some of them at readings. One can gain a sense of an individual’s giftedness and system of belief from such contact, but the purpose of this book is to enlarge our understandings, focusing on the reasons for each writer’s growth and the source of each poet’s illumination. This is hugely revealing. The poets’ candor exposes them and their work to us, encouraging us to read more of their poetry and to open ourselves to new and stirring visions of the transcendent.