Bound and free

"I now began to think seriously of breaking up housekeeping," Jarena Lee wrote, looking back on a pivotal moment in her life, "and forsaking all to preach the everlasting Gospel." In 1804, when Lee was in despair over her sins and on the brink of suicide, she heard the future African Methodist Episcopal bishop Richard Allen preach a sermon. That day, Lee found a people with whom she wanted to unite, and over the next several weeks she gained confidence in God's forgiveness and her own salvation.

Several years later, Lee began to preach, which upset Allen and other church leaders, who allowed women to serve as exhorters but restricted the ministry to educated, ordained men.

"Did not Mary first preach the risen Saviour?" Lee responded to her critics. Undeterred by critics, Jarena Lee relentlessly itinerated around the northeastern United States for three decades, calling on men and women, white and black, to confess their sins, accept divine salvation and seek the perfecting work of the Holy Spirit.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

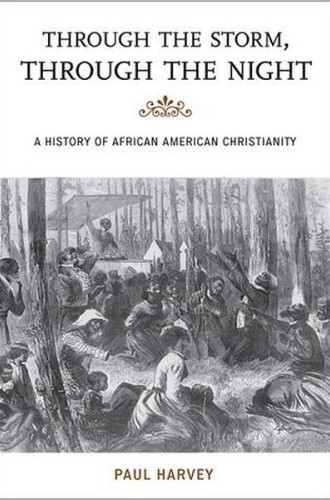

Women and men like Jarena Lee and Richard Allen populate Paul Harvey's brief introduction to the history of African-American Christianity. As his account of Lee's experience suggests, Harvey emphasizes both the fraught relationship between black and white Christians and the tensions within black religious institutions and communities.

Perhaps the most persistent of those tensions hinged on the degree to which African-American Protestants should strive for "respectability" in the eyes of white Christians (and certain black religious leaders) and suppress emotional forms of worship. AME leaders like Daniel Alexander Payne insisted that black Christians needed to leave behind ring shouts and other ecstatic practices associated with either Africa or slavery in order to gain the respect of whites. Not surprisingly, many black Christians disregarded such advice and continued to worship as they saw fit in secret plantation meetings, in the independent black churches that surged in number after the Civil War, and later in storefront churches.

Ironically, those black Christians who suppressed more ecstatic forms of worship still found themselves disdained and mistreated by those whites whose favor they had curried. When the elderly Payne was en route to a religious conference in the 1880s, a train conductor ordered him to move to the Jim Crow car. Payne refused, and the conductor forced him to leave the train five miles from his destination. The dignified Payne walked and carried his luggage the rest of the way. Payne was a conservative and sometimes condescending member of the black elite, but he was also a bold opponent of segregation.

Throughout his book, Harvey discusses the significance of music to black Christians, beginning with field hollers and moving from spirituals to gospel and eventually to rap. "Through the storm, through the night" comes from the pianist Thomas Dorsey's now-classic song, "Precious Lord, Take My Hand." The plea for God's protection amid the storms of life is a part of many black spirituals.

For centuries, Europeans and European Americans, including most Christians, denied the full humanity of black people. White Christians—not all, but far too many—enslaved Africans, obstructed the evangelism of their slaves, attempted to use Christianity to inoculate themselves against slave uprisings, denigrated black forms of worship, preached that the Bible prohibited intermarriage and ignored the poverty that harmed so many black communities. Given this context, it is hard not to admire women and men like Jarena Lee and John Marrant (a minister to black loyalists who emigrated to Canada during the American Revolution), as well as better-known figures such as David Walker, Sojourner Truth and Ella Baker. Black Christians responded to the injustices around them with a mixture of righteous anger, overtures of forgiveness, confidence in God's earthly and eternal care, and a hope that Jesus was leading them down "freedom's main line."

When he engages scholarly debates, such as those over the persistence of African religious beliefs and practices, Harvey writes with measured detachment. When he writes about the prophetic voices within black Christianity, one cannot fault him for employing a tone of appreciation. Despite the diversity of his subjects, nearly all of the individuals highlighted in Through the Storm displayed a steely courage rooted in their faith. Harvey includes figures not typically associated with the prophetic strain of black Protestantism, such as Charles Harrison Mason, the founder of the Church of God in Christ, long the nation's largest Pentecostal church. One wonders, though, whether Harvey's emphasis on the prophetic figures within black Christian communities leads him to understate the role of leaders less willing to boldly challenge racial oppression.

Harvey concludes his book with a discussion of Kanye West's 2004 hip-hop song "Jesus Walks." Readers like myself who do not typically listen to West should do a quick Internet search for the video version. Harvey includes the lyrics to "Jesus Walks" in a rich collection of primary sources that follow his text. West speaks to and echoes a black community that no longer revolves around the church.

Still, if the "black church" as the prophetic voice of a people has died (as Eddie Glaude Jr. argued recently), black churches—prophetic, conservative and many other varieties—are alive and well. "Listen to the sounds emanating from black congregations on a Sunday morning," Harvey concludes, "and the entire complex, diverse, and tenacious history of African American Christianity will come alive." The diversity, complexity and tenacity of the African-American religious experience come alive on Harvey's pages.

"Despite the occasional prominence of black churches and churchpeople in significant American historical events . . . most Americans have little sense of their rich and complex history," Harvey observes. His recovery of the voices of African Americans who wandered, endured and fought their way through the night is a very readable corrective to our collective amnesia. And Harvey's inclusion of 40 pages of primary sources makes this volume even more valuable for readers interested in an extended encounter with the women and men they meet in Through the Storm.