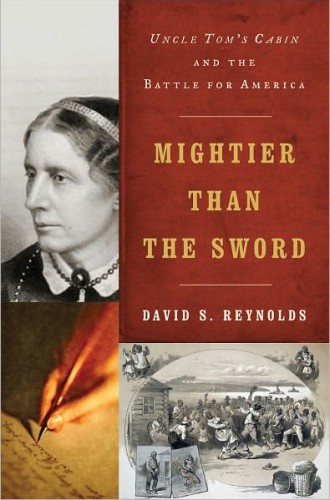

Mightier Than the Sword, by David S. Reynolds

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin stands alongside Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, Thomas Paine's Common Sense and Frederick Douglass's Narrative as an American classic. Any liberally educated person needs to know something about Eliza, Uncle Tom, Eva and the notorious Simon Legree. Stowe's novel filled the American imagination with the cruelty and injustice of slavery, and it may even have motivated some northerners to take up arms. Upon meeting Stowe for the first time in 1862, Abraham Lincoln allegedly greeted the most famous woman in America by asking, "Is this the little woman who made this great war?" With the 150th anniversary of the Civil War upon us, now would be a good time to dust off your paperback copy of the novel and either read it again or lend it to someone who has yet to enjoy it.

If you have read Uncle Tom's Cabin, then you should also read David Reynolds's Mightier Than the Sword. A professor of English and American studies at the City University of New York Graduate Center and the author of books on John Brown, Walt Whitman and America in the Age of Jackson, Reynolds has established himself as one of the great chroniclers of 19th-century American culture. His book is best described as a biography of Stowe's famous novel. Those who have not read Uncle Tom's Cabin will find Reynolds's book informative and interesting, but those who have spent some time with Stowe's masterpiece will find his interpretation of the novel and its place in American culture to be an intellectual feast.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Reynolds situates Stowe and Uncle Tom's Cabin in the evangelical culture of the early 19th-century United States. Stowe was raised in the most prominent religious family in the country. Her father, Lyman Beecher, was a nationally known Congregational minister and social reformer. Her brother Henry Ward Beecher followed in his father's footsteps and became, to use the title of Debby Applegate's wonderful biography, the most famous man in America. Her sister Catharine became an educator and advocate for women's rights. Although the Beecher family's theological roots were deeply embedded in 17th-century New England Puritanism, Lyman's children rejected their childhood Calvinism. Stowe's brand of evangelicalism was more hopeful than harsh, more democratic than hierarchical and more egalitarian than authoritative. She was a follower of revivalist Charles Finney, embraced the Wesleyan doctrine of perfectionism and even claimed that she was inspired to write Uncle Tom's Cabin by a vision from God. In the same way that the male members of her family used the pulpit to promote a brand of evangelicalism steeped in social reform, Stowe used her pen.

Uncle Tom's Cabin was not written in a vacuum. Many criticized the novel for its perceived sensationalism, but Reynolds argues that Stowe's treatment of slave life was quite mild compared to that of other popular reform novels of the era, such as George Lippard's dark and graphic The Quaker City; or, The Monks of Monk Hall. For Reynolds, Stowe's vision of reform was a moderate one. The novel celebrates women's rights but does not champion feminism. Her female characters are adventurous and sensual, but they are also virtuous and moral. The novel critiques capitalism and the slave system it produced, but it is not Marxist. It promotes temperance, but in a subtle and indirect manner.

The exception to Stowe's moderate approach, of course, is the novel's passionate and emotional condemnation of slavery. She was strongly influenced by some of the most radical abolitionists of her day, including Finney, Theodore Dwight Weld, Frederick Douglass, John Brown and Elijah Lovejoy. Stowe saw slavery as a national sin and hoped that her novel would help to eradicate it. When it came to the politics of slavery, she was the leading popularizer of the "higher law," a radical antislavery approach that "looked beyond the Constitution . . . to the law of natural justice, supported by God and morality." Stowe's commitment to higher law infuriated southerners, leading them to believe that if northern abolitionists were given the opportunity, they would run roughshod over America's founding documents, especially the U.S. Constitution, which did not condemn slavery.

Southerners discouraged the sale of Uncle Tom's Cabin and in some states made it a crime to read the book. Samuel Green, a Methodist minister and a free black man, was sentenced to ten years in the Maryland state penitentiary when a copy of Uncle Tom's Cabin was found on his person. The South responded to Stowe's novel with proslavery literature, but none of it could reverse the influence of her pen.

The most fascinating part of Mightier Than the Sword is Reynolds's treatment of the effect Uncle Tom's Cabin had on culture, both at home and abroad. Leo Tolstoy thought that the novel had a greater cultural impact than the works of Shakespeare because it promoted "the brotherhood of God and man." It may also have had some influence on Lenin and the Russian Revolution of 1917. Shortly after the Civil War, the American stage became flooded with "Uncle Tom plays." Rather than contributing to racial stereotypes, these plays, according to Reynolds, empowered African Americans by depicting strong black characters, connecting blacks to spirituals and other manifestations of African-American culture and providing opportunities for black actors. The Uncle Tom plays contributed to "a new kind of democracy." Many of them provided a view of Jim Crow America different from the one presented in popular movies, such as D. W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation (1915). In the 20th century, the novel and its various stage productions influenced positive portrayals of African-American life, such as Alex Haley's novel and the television miniseries Roots.

Finally, Reynolds considers the way that the character of Uncle Tom has been used as an epithet for African Americans who are considered to have accommodated too fully to white culture. Reynolds is puzzled by the way the lead character of Stowe's novel has been used in this way. He interprets Uncle Tom as a strong, responsible, family-centered black male and concludes that this image of Uncle Tom has clearly "won the day" as "time proved that the era's most effective force for social change was the firm-principled nonviolence of protesters like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr.—that is, those who were closest in spirit to Uncle Tom as Stowe portrayed him."

Uncle Tom's Cabin sold 310,000 copies in its first year of publication, and many more Americans were exposed to Stowe's story through family readings of the novel. After reading Mightier Than the Sword, I can't help thinking that it may be time to put away the smart phone, shut down the computer and continue to allow Stowe's novel to inspire us with a vision of Christian reform.