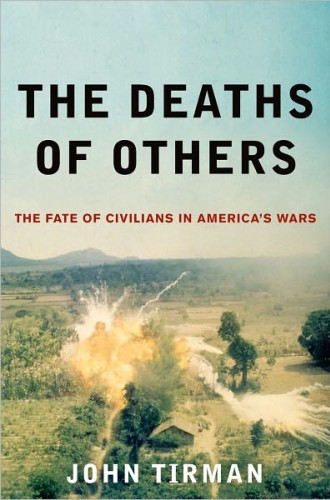

The Deaths of Others, by John Tirman

Friedrich Nietzsche observed that the human capacity to forget is not solely the result of inertia: "It is rather an active and in the strictest sense positive faculty of repression." According to Nietzsche, we forget not merely because we have to but because we want to—and we forget selectively, picking and choosing what we remember in order to construct the world in which we choose to live. At times such willful forgetting is an act of self-defense and even empowerment, but more often than not it is an act of self-deception. Frequently the results are tragic.

Nietzsche's insights about the nature of forgetting inform and direct this work by John Tirman. The Deaths of Others explores the history of the wars in which Americans have engaged, going back to the time of the first European settlers 400 years ago and extending to current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Tirman, executive director of the Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, seeks to uncover and explain a disturbing phenomenon: American wars are becoming more deadly, especially for noncombatants. Since the beginning of the 20th century, he writes, wars have caused the deaths of "more and more civilians as a share of total deaths, flipping the one-to-nine ratio of civilian-to-soldier mortality in the First World War to nine-to-one in many ethnic conflicts that occurred after the Cold War ended."

Tirman argues that the majority of Americans largely ignore the realities of modern war, including the disproportionate toll that military actions take on noncombatants. Although many Americans recognize and mourn the significant number of deaths suffered by U.S. troops in Korea (33,000 casualties), Vietnam (58,000), Iraq (4,500) and Afghanistan (over 1,000), far fewer can speak accurately about the civilian death tolls in these same conflicts: 750,000 in Korea, over a million in Vietnam and hundreds of thousands each in Iraq and Afghanistan. The American Civil War and World War I were extremely bloody conflicts, to be sure, but they were typified by exchanges between military forces on battlefields, and civilian deaths were the exception. As has been the case with recent conflicts in which the United States has been involved, population centers are increasingly becoming the ground zero of modern war.