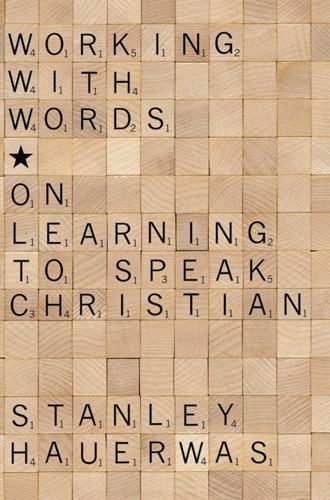

Speak Christian

In scriptoria and libraries, in liturgy and hymns, in sermons and table talk and retranslations of the Bible, Christian discourse has evolved to suit the needs of a church in endless conversation with itself and with God. Though it might not occur to most of us to think of Christian as a language, Stanley Hauerwas reminds us that as we live and move in Christian communities, we also learn from them ways of speaking about matters of the spirit that enable us to read together, address the world together, and enter into God's presence singing and into God's courts with praise.

Language is an instrument of power, impressed on our tongues and brains in ways that neurologists can describe, linguists can map and developmental psychologists can trace, but also in ways that are mysterious, unpredictable and regenerative. To speak is to act—creatively and consequentially—upon a world whose naming was the first authorization of humankind. "To converse" once had a broad range of meanings that included not just speaking but walking together, entering into community and communion with others.

Taking just such a high view of words, Hauerwas introduces his newest collection of essays and sermons with John Howard Yoder's observation that the task of theology is "working with words in the light of faith." Theology continues the essential mandate to name the creatures—ideas and concepts included—and to make elements into sacraments and sorrow into song. To speak in that context is to celebrate, a point Hauerwas illustrates by remarking that he enjoys Barth because "there is nothing desperate about his theology; rather it is a joyful celebration of the unending task of theology."