A review of The Shape of Participation

If you share my concern about the theological thinness of much of the current craze of construing Christianity as a practice, get Roger Owens's book. Even more, if you care about the theological identity of the church, you will find The Shape of Participation to be this decade's finest work of ecclesiology.

Beginning with the preaching of early American Methodist John Barritt and a recent Sunday at Mount Level Missionary Baptist Church in Durham, North Carolina, Owens notes that the church is indeed a community that is defined and sustained by practices. His modest and mundane beginning is a setup for some heavy theological rumination.

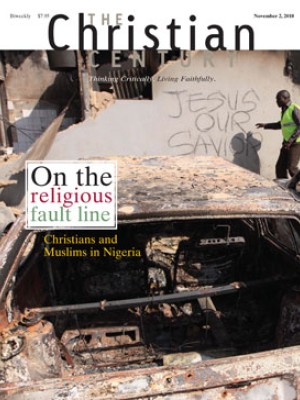

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Owens notes how James Gustafson's Treasure in Earthen Vessels (a book that was very important to me as a seminarian) confirms that the church shares many of the sociological characteristics of any human institution. Then he enlists Dietrich Bonhoeffer to show how Gustafson's sociological account, though influential on many contemporary descriptions of the church (including much of the practice movement), is insufficient to account for the peculiar nature of the church.

Bonhoeffer's ecclesiology, as well as his homiletics, leads Owens to make a guiding assertion: the church's practice is not primarily what we do but rather is shaped "as Christ practices himself in the church's proclamation." The most interesting of the church's practices are performed by Christ. "It is the Jesus Christ of the Gospels who is practicing himself in the practices of the church." Or as Bonhoeffer put it, when it comes to preaching, there is only one preacher: Christ.

Furthermore, because of the nature of Christ, the church's participation in God is embodied and visible. Christ continues to offer himself to the world "by practicing himself, in the Spirit, as the church." All attempts to discern the church's essence as somehow an interior or invisible relationship to God tend to make the church irrelevant, as well as the God-given practices that give birth to and sustain the church. An embodied, practiced, visible community is what you get with an embodied God.

Unlike me, Owens is a close-reading, in-depth theologian. He tackles the Radical Orthodoxy of John Milbank (Owens is both appreciative and critical), as well as Robert Jenson (Owens brilliantly shows the fruitfulness of Jenson's rigorous trinitarianism as a basis for ecclesiology). He then introduces readers to the agrarian Norman Wirzba. Finally, Owens constructively utilizes the mystagogical thought of Maximus the Confessor to give a robust trinitarian account of the practiced embodiment of the church. Much of this was slow, rough going for this reviewer, unaccustomed as I am to theology of the depth and rigor of that practiced by Owens.

Throughout the book Owens stresses the particularity and peculiarity of Christian practices like preaching and the sacraments as the unique, irreplaceable and deeply formative ways that a trinitarian God participates in human life through the church. Preaching and the sacraments of the church enable us to participate in the life of an unusual God. Readers (particularly pastors) who stay with Owens to the end of his exploration will be rewarded with a fresh rationale for their work in and for the church. As Owens says at the end, the best argument for the Trinity, and the best worship of the Trinity, "is the lived practices of real church communities living, in all their earthiness, the life of God in the world."

And my best commendation of this deep, dense, critical theological work is to note that it was produced by someone who is a pastor, who week in and week out practices the faith he so brilliantly elucidates.