Life after L'Abri

It seems ages ago that I spent a year at L’Abri, the Christian work-study community in the Swiss Alps. But I remember very well how I felt about the place. It was not the feeling one gets on a lazy beach vacation, where life is simplified. If anything, it was quite the opposite. At L’Abri everything had great import. It seemed that everything we did, felt and thought really mattered. It seemed that we had a glimpse of God’s perspective—and maybe we did.

It was the mid-1970s when, like many others in their twenties, I put on a backpack and set out for Europe. I did not plan to go to L’Abri; I didn’t even know it existed. Nor was I familiar with evangelical Christianity. I was a native of Newark, New Jersey, the child of a Jewish, Catholic, immigrant, nonreligious family—an atheistic feminist committed to everything liberal. I had decided to hitchhike around for a year. Since I didn’t have much money, I perked up when someone told me there was a place in the Alps where they’d give you a bed, feed you, and let you stay as long as you liked for free. I figured it must be some kind of hippie commune. So I hitched a ride to the community of chalets in the small village of Huemoz, in the canton of Vaud, just down from the ski resort of Villars.

At first I was disgusted to realize the place had something to do with religion, but I did feel welcomed. There were plenty of young people in bell-bottom jeans lounging outside the chalets, working in the gardens or sitting together, engaged in deep conversations. Everyone seemed interested in everyone else’s beliefs, background, dreams and goals.

These young people were an assorted bunch. Some were disaffected Europeans, wondering if truth could even be found anymore. Many were American baby-boomer radicals, exhilarated by the cultural revolution yet disillusioned by the attendant crises and searching for something to believe in. And then there were the evangelicals. By the 1970s, L’Abri was a pilgrimage site for them. Raised in conservative households, they were now no longer sure their inherited beliefs held up intellectually. They came to L’Abri because the founder and leader of the community, Francis Schaeffer, was seen as the intellectual pinnacle of evangelical theology. They had heard his taped lectures or read his books, in which he asserted that there are rational reasons for faith and that contemporary culture should be addressed rather than avoided by evangelical believers. The days of the fundamentalist retreat from the world had to end, according to him.

I had never heard of Schaeffer, and I was immediately repulsed by the many young men at L’Abri who patterned themselves after this little old guy in knickers and knee socks, with his lugubrious demeanor and somewhat defensive, argumentative style. To me his message sounded authoritarian—believe the Bible, or else. And sexist—women, submit to men, or else. Yet with his long hair and beard he could be mistaken for a hippie, and he did assess American culture critically in a way I found compelling.

His wife, Edith, was even more outside my ken. She lectured not on philosophy but on how to live a holy Christian life. The young evangelical women at L’Abri took her as their role model. She seemed perfect, with her classy outfits, well-set tables, good manners and unflappable piety.

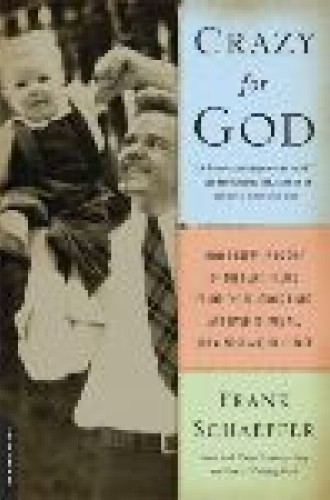

Frank (then Franky) Schaeffer, youngest son of Francis and Edith Schaeffer, grew up hearing his father’s lectures and his mother’s prayers and witnessing the passionate searching by young people like me. But as its subtitle suggests, Frank’s book is not another homage to the Schaeffer and L’Abri legacy. It is his mea culpa for his part in taking his father away from theological work and into the world of American religious-right politics.

The elder Schaeffer was sent to postwar Europe by the fundamentalist Bible Presbyterian Church, inspired by Carl McIntire. His goal was to revitalize and unite Reformed churches in Europe. He wasn’t planning to start a religious commune. L’Abri evolved as the Schaeffers’ daughters brought fellow private-school students home from school. The Schaeffers offered hospitality, a compassionate ear and clear teaching on the Christian gospel. After Schaeffer was abandoned by the church’s mission board, Francis and Edith stayed in Europe. By the time Frank came along, the hospitality had morphed into L’Abri and was accommodating hundreds of seekers for several months at a time. The community made do with meager resources, lived on faith, prayed for daily needs and welcomed all who came.

Frank’s story is about how, with his help, this community of essentially world-denying U.S. fundamentalists joined up with activist right-wing U.S. politics. It started, Frank says, when Billy Zeoli, a high-rolling evangelical from Gospel Films, came to L’Abri. Zeoli and Franky cooked up the idea of making a film series that would take the Schaeffer critique of American culture to a wider audience. Until then, Frank says, “Dad, with his preference for the small-is-beautiful hippie ethos, . . . had avoided the temptation to capitalize on his growing fame.”

Zeoli offered access to the “easy money” of the evangelical world, and Frank, barely 20, married and already expecting his second child, needed that money. He also saw a way he could move from being an unknown painter to being a well-known filmmaker. His Dad wanted his son’s success too, so they all “swallowed hard” and agreed. Two film series and books eventually resulted: How Should We Then Live? followed by Whatever Happened to the Human Race?

Through the savvy marketing of evangelical friends, a veritable Schaeffer phenomenon was created. Zeoli, “with his multimillion dollar backing from the Amway Corporation and its far-right founder-capitalist-guru Rich DeVos, was about as slick and worldly and far away from the L’Abri way as anyone could get,” contends Frank. The Schaeffers were courted by and drawn into the world of right-wing leaders such as Dallas oil emperor Bunker Hunt. A pivotal connection was made with congressmember Jack Kemp (who became HUD secretary under Reagan). Kemp and his wife, Joanne, began hosting Schaeffer discussion groups and introducing the family to Republican representatives and senators. Writes Frank: “Soon I got used to telling wealthy evangelicals that it was time to ‘take our country back,’ to ‘answer the humanists,’ to ‘defend our young people.’ . . . I was starting to see that it paid handsomely to babble loudly about Christ and saving America and to present myself—and Mom and Dad and our new ‘ministry through film’—as the last best defense of truth against the enemies of the Lord.”

The next seemingly inevitable step was jumping into the antiabortion movement. The senior Schaeffer had long identified abortion as largely a Roman Catholic concern. When father and son started to make How Should We Then Live? Frank says, “Dad had not wanted to even mention” abortion. His reticence may have had something to do with the inherent anti-Catholicism of Protestant fundamentalism.

But as a teen Frank had gotten a student pregnant, married her and become a very young father. Out of this, he says, came an “antiabortion fervor” that he pressed on his father. Once he had persuaded his father of the “prophetic” nature of his concern—and with the encouragement of old family friend and future surgeon general C. Everett Koop—the issue was included prominently in several film episodes. As a result, even Catholics began to take this evangelical preacher seriously. So another link in the chain joining Protestant evangelicalism with right-wing politics was forged.

In the end, the formerly apolitical ethos was abandoned. “There was no more talk about avoiding becoming too political. Through the How Should We Then Live? film series, book, and seminars, my father had been able to reach more people . . . in a few months than in his whole previous lifetime. And Dad enjoyed the attention.”

Firsthand experience of such conservative icons as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson and James Dobson led to Frank’s eventual disillusionment with American evangelicalism. At its worst, the religious right was “the merging of the entertainment business with faith, the flippant lightweight kitsch of American Christianity, the sheer stupidity, the paranoia of the American right-wing enterprise, the platitude married to pop culture.”

Though the author shows fondness and respect for his parents, he also points to their competitive, emotionally mismatched and somewhat abusive relationship. The Schaeffer family style was not much more dysfunctional than many others—or was worse only because of how the family had to hide its disharmonies in order to conform to their public image as the perfect Christian family. “Some people literally worshipped my parents. They still do. A lady rushed up to me at one of our seminars and asked if she could shake Dad’s hand. I told her that he had already left, which he had, and she grabbed me and blurted ‘I just want to say I touched a Schaeffer!’”

As the admittedly spoiled yet neglected baby of the family, Frank shows how too much focus on mission can leave a lot of other life issues unattended. Frank has many of the same blind spots as his parents. He seems to have barely noticed the community’s rank sexism—perhaps because he benefited from it. Although he clearly loves the L’Abri groupie he married, he demonstrates little repentance for sacrifices she made to further his career. He objects neither to the evangelical ideal of the “perfect Christian family,” nor to the rhetorical violence of fundamentalist theology, nor to the bait-and-switch tactics by which young people, drawn in by a countercultural presentation, are taught that liberal is a dirty word.

I was left feeling a bit sorry for Frank. Rather than loosening his conviction that humans can know the mind of God, by the end he seems to have reduced issues of faith to habit and early patterning. As he describes it in the book, his move to Eastern Orthodoxy—a move a significant segment of evangelicals have made—seems less about finding a richer ritualistic, historical and theological life than about continuing the evangelical search for purity and unsullied origins.

But, like Frank, I am appalled by what became of the mostly benign environment that was L’Abri. It is disturbing to see how the movement that introduced me to Christ helped start a destructive culture war and made many associate Christianity with narrow exclusivism. Many things that L’Abri professed and practiced had great influence on conservative culture—the gendered division of labor, stiff formality at meals, the use of code words, elitist confidence in one form of Christianity, and a sense of impending crisis.

The story of L’Abri shows how deeply intertwined are theology and behavior. It also illustrates the emotional balance that deep faith can provide when love and compassion, rather than an insistence on rightness, prevail. “When I left evangelicalism,” Frank writes, “ it was certainly not because I was disillusioned with the faith of my early childhood. I have sweet (if somewhat nutty) memories of all those days of prayer, fasting, and ‘wrestling with principalities and powers.’ We might have been deluded, but we weren’t unhappy. And there are a lot worse things than parents who keep you away from TV, grasping materialism, and hype, and let you run free and use your imagination.”

I know what he means. I outgrew much of the theology and practices I learned at l’Abri. Yet my conversion to Christ was no illusion. For although I sojourned with the evangelicals only briefly, my youthful year at L’Abri was pivotal for a lifetime. There I found a caring community and people who took seriously my intellectual quandaries about life, death and meaning. There I learned that theology, the joining of mind and spirit, is essential to healthy faith. My chosen vocation of teaching is a witness to my time there. Like many others who passed through its doors, I still show the imprint of L’Abri.