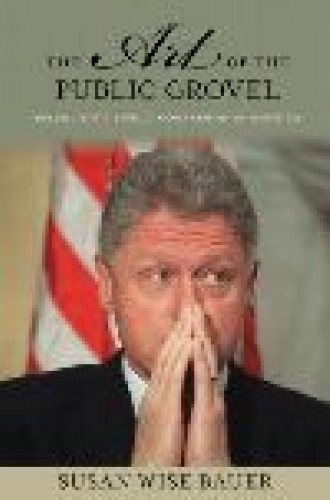

Fessing up

What do Bill Clinton and Jimmy Swaggart have in common? Each made a spectacular public confession of sexual misconduct. And according to Susan Wise Bauer, a historian at the College of William and Mary, their mode of confession took the form that the American public wants—one rooted in evangelical practice. Evangelical culture is so deeply intertwined with American culture that it has provided the blueprint for public confessions, a fact that poses a challenge to those who are unfamiliar with the genre when they get caught with their pants down.

The scandals may be sexual or financial, but when public figures follow the right script, they are more likely to be welcomed back. The current governor of Illinois may want to take notes.

The ones who know how to feed the dragon come out all right, Bauer says. For example, after Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky and his lies about it were exposed, he drew on his Baptist roots and delivered a confession that helped rescue his public image.

Whatever your opinion of Clinton, you cannot help being in awe of his journey back from the brink. Two months after the House impeached Clinton for perjury, the Senate voted to acquit him. He left office with a 65 percent approval rating—the highest in presidential history. His 2004 autobiography sold more than 400,000 copies, and he won a Grammy for the audio version. During Hillary Clinton’s recent presidential campaign, her husband was kept out of the spotlight so as not to draw attention to the fact that he got more favorable attention than his wife.

Four years after Clinton’s confession, Cardinal Bernard Law of Boston offered his own confession—but this one did not do the trick. Law acknowledged his role in perpetuating the sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church in legalistic and frosty words: “I acknowledge my own responsibility for decisions which led to intense suffering.” He didn’t express personal regret and shame that were equal to the seriousness of the sins. Law never gave the American public what it wanted: an evangelical-style public confession in which he was visibly sorrowful and admitted his wrongdoing.

A Catholic like Cardinal Law, belonging to a religious tradition that emphasizes private confession, is at something of a disadvantage when it comes to making the kind of public confession that Americans crave. Bauer suggests, however, that even most Catholics, having been influenced by the evangelical model of confession, wanted to hear something more personal and heartfelt from Cardinal Law. Within weeks, Law’s fellow priests called for his resignation, forcing him to step down from his duties in Boston and move to Rome.

In the Gospel of Matthew, Peter asks Jesus, “Lord, if another member of the church sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?” To which Jesus replies, “Not seven times, but, I tell you, 77 times.”

Christians follow these instructions inconsistently. Through out history, there are cases of leaders—in politics, religion and the arts—committing the same offense but receiving different punishments. So who gets to make a comeback from sin, and why?

Bauer argues that in order to secure forgiveness from the American public, sinners must make a confession containing three elements. First, the one confessing needs to publicly admit to the wrongdoing without making excuses for it, and needs to present himself or herself as an ordinary person.

Second, the confession must refer to spiritual war between good and evil and indicate that the one confessing, though once overcome by evil, has now chosen to fight on the side of good.

Finally, the one confessing needs to acknowledge that his or her career is now in the hands of the people. The confession must offer power back to the people and give them the choice of whether to forgive.

Perhaps the best example of this mode of repentance is the case of Assemblies of God televangelist Jimmy Swaggart. After being caught entering a motel with a prostitute in 1988, Swaggart, known as a champion of conservative family values, addressed his church and gave a classic evangelical confession. “I take the responsibility,” he said. “I take the blame.” Much of this apology was captured by news cameras. The close-up images of Swaggart’s tear-stained face remain iconic.

Swaggart was defrocked for just one year, after which 5,000 people attended his church for his comeback sermon, and his television broadcast that day reached 800,000 households. Clearly, Swaggart had been forgiven. Bauer suggests that years later, and from a very different place on the political spectrum, Clinton may have used Swaggart’s confession as his model, consciously or otherwise.

Bauer’s schema works pretty well when it comes to analyzing the clunkers as well as the successes. Cardinal Law was not forthcoming with the public, he did not acknowledge that the issue of child-molesting priests represented a struggle between good and evil, and he never gave the impression that he had moved from one side of that fight to the other. In his vague, distant remarks, he failed to take sufficient blame, and in appealing to church hierarchies and rules—which were not transparent to the laity—he never acknowledged that his power came from the people. In fact, he showed himself to be a product of a system in which power is not seen as coming from church members.

In a strange twist, another example of a failed public confession comes from the same man who got it so right the first time. Three years after his first confession, Jimmy Swaggart was arrested for a traffic violation when he had a prostitute in his car. This time around he announced to his congregation, which had forgiven him the previous time, that God had told him to keep on preaching. “The Lord told me flat out it’s none of your business,” he said. Deprived of a confession, the congregation rapidly diminished until in 1998 large sections of the church were empty and roped off and the building was literally falling down.

When did the current ritual of public confession begin? In reviewing the history, Bauer points to two paradigmatic figures who illustrate the changing understandings of public confession. She cites Grover Cleveland as the last public figure to survive a scandal without making a public confession. During his 1884 presidential campaign, Cleveland was revealed to have an illegitimate daughter. Cleveland did not address the matter directly. Instead, his Presbyterian minister spoke on his behalf, assuring the public that the matter was being dealt with spiritually. The public accepted this approach, and Cleveland was elected.

Bauer also points to the 1969 case of Ted Kennedy, who made a botched confession when dealing with his defining scandal. According to Bauer, Kennedy’s delay in speaking publicly about the death of a young woman who had been riding in his car when it went off a bridge in Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts, reflected both his Catholic belief in private confession and his aristocratic sense that he did not owe anything to ordinary people. When Kennedy finally spoke publicly about the events, his remarks were full of medical explanations for why he did not report the incident to emergency personnel right away. “My conduct and conversations during the next several hours, to the extent that I can remember them, make no sense to me at all,” he said.

While Kennedy remained in politics and has had enormous influence in the U.S. Senate, his chances for being nominated for president suffered a fatal blow. His patrician remarks of explanation to the people of Massachusetts showed too little emotion (“In the morning, with my mind somewhat more lucid, I made an effort to call a family legal adviser . . .”) and came too late.

After Chappaquiddick, American culture grew increasingly confessional, with talk psychologists plying their trade on radio and television and with an explosion of tell-all memoirs. The 1980s also saw the rise within conservative Christian circles of a particular notion of a battle between good and evil, one framed in the culture-war terms of godliness and secular humanism.

The rise of both a left-leaning therapeutic culture and conservative Christianity created a new context for public confession: public figures now needed to make extensive confessions in order to be forgiven of wrongdoing. Some did it well and survived. Others did it poorly and were not received back into the public embrace.

In this year’s spin of the roulette wheel of public confession, New York governor Eliot Spitzer confessed to a dalliance with a prostitute. His beautiful and accomplished wife stood by him during his public apology in March. Watching this event, I had the reaction that many other women did in seeing Silda Wall Spitzer stand by her husband and try to keep her composure— I found myself yelling at the television, saying: “Leave your wife at home, buddy, and take your punishment like a man.” I didn’t want to see Silda Spitzer dressed up and ready for the cameras. I wanted her to be at home on the couch in her pajamas with a big glass of wine, yelling at the television herself, and then yelling at her husband when he got home—all without having to look serene and supportive in the public eye.

Spitzer’s confession was the first to raise a nationwide conversation about why a woman should have to go through this ritual with her husband. Why does the wife have to walk the plank too? Public opinion turned against Spitzer for including his wife in his public appearances, as well as for his cold and unforthcoming manner of confession. He did not follow the rules.

A twist on the role of supportive wife came from Dina Matos McGreevey, the wife of former New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey. In the wake of the Spitzer scandal, Dina McGreevey appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show to explain why she had stood by her husband after he confessed to having an affair with a man. In her 2007 memoir Silent Partner, McGreevey wrote about the experience of standing by the one confessing his sins. Just four years earlier, it had been Jim McGreevey himself who was on Oprah, to promote his memoir The Confession. As America recalled these past scandals in the wake of the Spitzer fiasco, the world of political gossip seemed to be turning in upon itself, like a hungry dog attempting to eat its own tail.

Seeing Dina Matos McGreevey on Oprah, I realized that I didn’t just want the wronged wife to stay home—I wanted them all to stay home. I had had my fill of these tragic personal dramas played out on a public stage. I had no desire to see the Spitzers squirm in front of the cameras. I knew that no spiritual or public good would come of it. I wanted the legal system to do its work, but I wished that the spiritual work of confession could be done in private, in a community of faith, and that the rest of us would just back off.

Public figures’ emotionally wrought public confessions leave me feeling used. Whether done well or badly, according to Bauer’s terms, such a confession has a cynical purpose: the restoration of one’s career.

It is as if the American public has entered into a devil’s bargain. You, the sinner, must share the lascivious personal details of your life. We, the public, will be disgusted by them but are nonetheless hungry to know about them. If we judge your performance to be sincere and complete, we will restore you to power. This is a spiritually barbaric ritual, one that we may look back on with the same disgust with which we view gladiators at the Coliseum and the mad crowds who paid to see them fight.

The American public has not simply been spoon-fed these confessions. It longs to hear them. If people refused to watch the shows or read the publications that tell these stories, the media would have less incentive to produce such material.

Can people of faith lead the way in restoring con fession to its rightful place? Christians can remind people that confession is ultimately to be directed to God and not to an audience. As people who believe in divine reconciliation, we can insist that the aggrieved parties be addressed directly, without all of us sitting in on the conversation. Most important, as people who believe in confession, we can confess our own sin of voyeurism.

I wonder if we will ever again hear a public figure’s minister say, as in the case of Grover Cleveland, that the individual is working on the state of his or her soul. And would the nation then agree to back off? Given that the clergy have occasionally allowed themselves to be used in these public spectacles, this may not be likely. To return to the masterful confession of Bill Clinton, part of his act of confession was arranging highly publicized visits with several of America’s most famous clergy. I watched on the news as these men entered and exited the White House—and even commented to the press—and I found myself wondering which one of them was his real pastor.

Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich was reported to have met with clergy in the days following his arrest on corruption charges. I wonder if we will soon be privy to another public confession.

Away from the television cameras, it makes a difference when pastors and parishioners talk together in a spirit of confession. Most churchgoing Ameri cans understand this and might be getting ready to let go of the public confession that smacks of showbiz. But we will have to practice the compassion that our faith compels. If we have grieved with the families who are disgraced in such situations and have prayed for them intensely, we might be less likely to pick up the magazine that rips open their lives for entertainment value.

Jesus says we are to forgive 77 times. Our culture has flipped that instruction around. Instead, we want to hear a person confess 77 times—and even then, we borrow God’s job description and do the judging ourselves.

Sometimes the confessions sound false. We have seen and heard so many of them that we have trouble believing they’re sincere. Sometimes the people confessing obfuscate and make excuses; they do not deliver the remorse we think is needed. But I would argue that no confession can be meaningful in such a setting.

Apologies should be delivered in public, with gravitas and purpose. But the spiritual work of remorse and confession, the difficult restoration of the family and the desperate prayers for grace should all take place in more intimate spaces, such as the living room, the pastor’s study and in the company of saints who worship together week after week. In church, we all find the need for that prayer of confession, and we can each find something within us to contribute. And it is there that we meet Jesus, who told us to forgive 77 times. He seemed to know that we would all be in need of it at least that often.