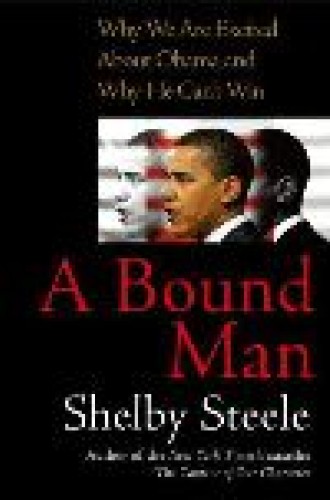

Obama's bind

Black public figures seem to fall into one of two categories: they either project a militant resistance to white racism and its pervasive legacy or a generous willingness to look past that tortured history for the sake of an interracial future. Choose your model: W. E. B. DuBois or Booker T. Washington? Al Sharpton or Colin Powell? Angela Davis or Oprah Winfrey? Dick Gregory or Bill Cosby?

The black social critic Shelby Steele formulates the contrast this way: black leaders must choose between being “bargainers” with white America and “challengers” of it. The bargainers implicitly make a deal with whites: “I will not use America’s terrible history of white racism against you if you will promise not to use my race against me.” Bargainers “grant whites their innocence . . . in return for their goodwill and generosity.” Hence the successful, apparently race-blind careers of people like Powell, Winfrey and Cosby.

Challengers, on the other hand, “presume whites to be guilty of racism” until proven otherwise. Whereas bargainers try to act as though race makes no difference, challengers find their identity and moral authority precisely in their blackness. Thus figures like Malcolm X, Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

Each stance has advantages and disadvantages. Challengers, even though they set themselves against white America, have a peculiar power over it—the power to arbitrate who is and isn’t racist. When radio host Don Imus sought absolution for his racist remarks, he reached out to Sharpton, not Powell. When TV producers want the “black perspective,” they reflexively turn to Jesse Jackson. In a curious way, white Americans accord a special (if limited) place to challengers.

But bargainers are also welcome, and there is no better example than Oprah Winfrey. By trusting that white Americans will naturally sympathize with her personal struggles over self-esteem or weight, and by empathetically discussing a host of issues in which race is not a factor, Oprah implicitly absolves her audience of racism. She grants whites their innocence. “Her audience is rightly flattered,” observes Steele, “and it sends back waves of gratitude in the form of love, admiration and affection.”

Whatever advantage each stance has, each is still a pose, a mask—and wearing the mask takes a toll. The price paid by the bargainers, notes Steele, is self-suppression: they must hide their anger at whites and never stress their racial identity, since that would break the terms of the bargain. The price for the challengers is losing their authenticity as unique persons, each with a nuanced set of responses to the world, since a challenger cannot swerve from being the representative of race-based concerns.

A huge part of Barack Obama’s appeal is that he appears to transcend this bleak set of options. He is a former community organizer who speaks eloquently, in the style of the African-American church, about the plight of people on society’s margins. But he is also a graduate of elite schools who seems to bear no personal scars from racial discrimination and no animosity. In the case of Obama, Steele’s forced choice seems an irrelevant remnant of the 1960s.

But don’t be fooled, says Steele: Obama remains bound by these two categories. The more he plays on his skills as a bargainer and ignores racial difference, the more suspect he will be among blacks, who will judge that he is not “black enough.” And to the extent that he plays the role of racial challenger and speaks on behalf of blacks, he will lose the confidence of whites. Caught in that racial bind, Obama can’t win.

Steele, a fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford, wrote his book in the final months of 2007 so he could not have known how the Democratic primaries would unfold. Until the South Carolina primary in late January, it was not evident how well Obama would be received by black voters. But he won 80 percent of the black vote there, and his appeal among blacks has not wavered (recent polls show him winning 90 percent of the black vote). That is true even though he has made some pointed challenges to the black community—urging black men to take more responsibility for raising and educating their children, and speaking bluntly about vices as well as virtues in the black community. In other words, Obama has taken some calculated steps away from the role of challenger without losing black support—a refutation of Steele’s thesis.

But if the “not black enough” argument has failed to gain traction among black voters, it clearly strikes a chord among some black leaders, apparently at a visceral level. How else to explain the unraveling of Jeremiah Wright except as the case of a black leader so accustomed to the role of challenger that he could not abide Obama’s success as (in his eyes) a bargainer—or, as Wright put it, “just another politician who says what he needs to say.” Jesse Jackson’s charge, accompanied by the n-word, that Obama is “talking down to blacks” when he criticizes absentee fathers, appears to be another complaint of a perennial race-based challenger irritated by the success of someone who thinks he can transcend race. Watching the recent behavior of Wright and Jackson, Steele surely must have felt that his analysis of leadership styles was richly confirmed.

Steele’s deepest worries about Obama are not about his political chances but about his personal authenticity. Whether as bargainer or challenger or some creative mix of the two, Steele thinks, a black leader must don a mask, forging a persona that will charm or manipulate whites. In taking on this task, Steele contends, black leaders lose themselves, for they are never able to locate what they themselves really think. Steele wonders: Is Obama running for president because of his deep convictions or simply because he is aware of “his power to enthrall whites”?

But questions of authenticity can be raised about every politician. The peculiar job of a politician is to fashion repeatedly points of agreement between people with different and shifting points of view and to project a public persona that can elicit action and be the vehicle for people’s hopes. If personal authenticity is your quest, politics is the wrong medium. We can wish for congruence between the inner and the outer person of the politician, but in the end what matters for the voters is the direction of the policies chosen and the decisions made.

Steele must hope, at some level, that his binary analysis turns out to be wrong and that Obama’s campaign breaks open new models of black leadership. We will know more in November.