Walled in

The winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, The Lives of Others, looks at a political system kept in power by a police agency that has absolute power to keep any citizen under constant surveillance. The ingeniously titled film, written and directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, is the first major German movie to dramatize the convoluted machinations of the Stasi, the East German spy apparatus that served as “the sword and shield of the Communist Party”—an ironically appropriate motto, since in practice that sword was employed against the citizens of the German Democratic Republic.

The abuses of the Stasi—especially its willingness to blackmail East Germans into spying on each other—do not come as a revelation at this point. And von Donnersmarck’s talent isn’t for machine-gun-style political melodrama that sustains a tone of outraged irony, as do the films of Constantin Costa-Gavras, which became famous decades ago (Z, State of Siege) and have served as the model for many political filmmakers. This director works more thoughtfully and methodically (the film takes two and a half hours to unfold). But he does surprise you. The movie is not what its set-up leads you to expect.

The film sets up an opposition between a successful East German playwright, Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), and a Stasi captain, Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe). Dreyman has never indicated, by word or deed, the slightest dissatisfaction with the government, and as the only East German writer whose work is taken seriously in the West, he serves the state’s purpose. But a government official (Thomas Thieme) who has manipulated Dreyman’s live-in girlfriend, Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck)—also East Berlin’s most celebrated actress—into sleeping with him decides to get Dreyman out of the way. He persuades a Stasi colonel, Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur), to bug Dreyman’s house and tells him to uncover something subversive about the playwright. Grubitz gives the assignment to Wiesler.

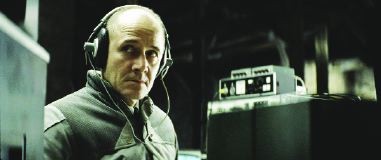

Wiesler is thorough and ruthless. When he addresses a class of Stasi recruits on interrogation methods and one of the pupils balks at the inhumane treatment, Wiesler makes a discreet black mark beside the pupil’s name. He is humorless and obsessive—a true creature of the party. Unlike Grubitz, who is worldly and enjoys power for its own sake, Wiesler is devoted to communist principles. When he sets up shop in a basement across the street from Dreyman, we fear for the playwright, since Dreyman’s friends and fellow artists are less circumspect politically, and Dreyman has been working on behalf of a close friend, Albert Jerska (Volkmar Kleinert), a gifted music director who has been blackballed by the government for a decade.

Wiesler bears some resemblance to Javert, the sleepless cop who pursues Jean Valjean in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. He is closer to Harry Caul, the reclusive surveillance expert whom Gene Hackman played in The Conversation. Wiesler has even less of a private life than Caul, though we can see that he longs for something more that he can’t, or won’t, articulate even to himself. Like Caul, he enters deeply into the lives of those he is assigned to track. The way he does this—and why—occupies the movie’s second half.

At one point in the movie Dreyman sits down at the piano to play a piece Jerska gave him—“Sonata for a Good Man.” This sincere, wordless performance stirs Wiesler. The identity of the “good man” of the sonata keeps changing as the movie proceeds. The tragic fates of some of the film’s characters are countered by its faith in these good men. The atmosphere of paranoia and cynicism breaks open in a way that leads thematically to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. The movie’s humanism feels hard-won and legitimate.