Hope in Bethlehem

The suffering of the Palestinians under Israeli occupation can be documented through broad statistics: the number of people killed and injured, the number of days under curfew, the number of demolished houses, uprooted trees and confiscated land. It can be described by noting the difficulties in crossing checkpoints to get to jobs, schools and hospitals, and the physical and psychological hardships imposed by the “wall,” which is cutting Palestinians off from land, water, access to basic services and to each other. But it is hard to understand what all this means without seeing and experiencing it for oneself.

I have taken many delegations to Palestine so that people from the West may come to understand this situation directly. Invariably people are stunned by the utter oppressiveness of the policies under which Palestinians live. Such visits have become more difficult, however, as Israelis tell Westerners that they are not allowed to visit the West Bank, not even areas near Jerusalem, like Bethlehem, “because it is too dangerous.” Let me assure anyone interested in such a trip that going to Bethlehem is not dangerous. Rather, the Israeli warnings are meant to keep us away from a world they don’t want us to see.

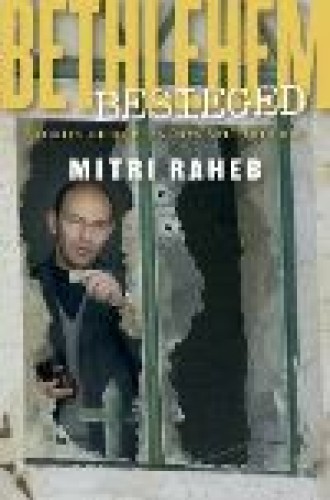

Short of a personal visit, perhaps the next best way to understand what the Israeli occupation means for Palestinians is to see a well-crafted video or to read a book that tells the stories of what everyday life is like under occupation. Mitri Raheb, pastor of Christmas Lutheran Church in Bethlehem, has given us such a book. A delegation I led to Palestine last January was based at and organized by the International Center of Christmas Church, with many of our sessions led by Raheb. There I heard many of the stories and saw many of the aftereffects of the events described in this book. Reading it brought this reality back to me with great poignancy.

Bethlehem was under direct occupation and siege by Israeli troops for 40 days in April-May of 2002. The 135,000 people of the Bethlehem region were under curfew for four months, confined to their houses except for brief respites to shop. During the siege much of the work done by the Bethlehem community to refurbish the city for the hoped-for influx of tourists in 2000 was destroyed, and Bethlehem itself became largely inaccessible to the outside world.

This pattern of seeking to isolate Bethlehem and the rest of the West Bank continues and worsens today, especially with the building of the wall, which strangles communities by confining them to small ghettos cut off from each other. The purpose of this isolation has little to do with “security,” the official Israeli rationale. As one Palestinian told us, “Terrorists don’t use checkpoints.” Rather the goal is to make daily life so impossible that more and more Palestinians will give up and leave the country. It is a kind of ethnic cleansing.

Raheb’s ministry is a quiet but steady effort to defeat this agenda, to help his community, Christian and Muslim, not to lose hope, not to give up. As he says in the introduction, to tell one’s story by writing such a book is a primary act of nonviolent resistance, a refusal to be silenced. This entails more than simply refusing to leave. It entails the creative transformation of oppression—to refuse to dehumanize those who dehumanize you, to refuse to make Israelis into enemies, to refuse to stop dreaming of living together as friends and neighbors.

During the siege of Bethlehem, the International Center of Christmas Church was occupied by 300 Israeli soldiers. They not only used it as a base to besiege the rest of the town; they also did considerable wanton damage to the facilities, destroying most of the windows and doors, smashing computers, blowing holes in walls and floors. On one occasion 12 soldiers rampaged through Raheb’s own office. When Raheb told the soldiers that he refused to turn them into enemies but wanted to relate to them as neighbors, the commanding officer told him to “shut up.” Only the direct intervention of the ambassadors from Sweden and Norway, who appealed to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, got the soldiers to leave.

As soon as the soldiers were gone, the people of Christmas Church began picking up the pieces and planning to rebuild. As an expression of the creative transformation of the violence they had experienced, they turned some of the broken glass and spent bullets into pieces for mosaics that depicted the occupation. Today the International Center is rebuilt and is expanding its plans to be a center of hope for the whole community. The arts, music, theater and computer education that take place there allow people not only to express their experience, but to communicate with others throughout the Palestinian region and the rest of the world. It allows the people of Bethlehem to overcome their imposed isolation.

The stories Raheb tells in Bethlehem Besieged are not only about the victimization of Palestinians; they are about Palestinians’ refusal to become victims, about their insistence on renewing their capacity to be creative and hopeful human beings, and to reach out to others—mostly notably to Israelis—to reciprocate. This is a book that urgently needs to be read by those longing for signs of hope in what is surely one of the most troubled places on earth.