Poems of witness

Molly McCully Brown recovers the lives of women at an institution notorious for its eugenics program.

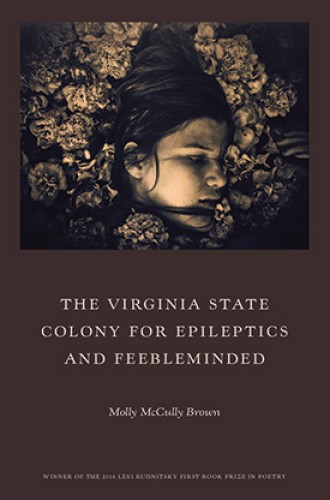

When poetry gives voice to those who have no voice—those who are dead, marginalized, or ignored—it helps resurrect lives from oblivion. Such poems are called “poems of witness.” Molly McCully Brown’s superb new collection, which won Persea Books’ 2016 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize, exemplifies this form.

Historically, institutions for the mentally ill have a reputation for cruelty and abuse. Treatments, which varied widely from the 18th through 20th centuries, included shackling, placement in solitary confinement, forced feeding, shock treatments, and lobotomies. These treatments were meted out to people suffering from what we would today classify in any number of ways: bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression, or even simple rebelliousness.

The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, which is the focus of Brown’s book, opened in 1910. The hospital became notorious for its eugenics program, in which undesirable “imbeciles” and “degenerates” were sterilized, often without their knowledge or understanding. In 1927, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Buck v. Bell gave states wide latitude to sterilize men and women. It is estimated that the state of Virginia sterilized somewhere between 7,000 and 8,300 inmates through the 1970s. Brown’s attempt to recover the lives of some of these people is both a historic project and a poetic one. In both respects, her book succeeds marvelously.

Brown rejects simple narrative. Where no clear narrative can be found, she brings her active imagination and empathy to bear upon what remains. She examines the material objects of the hospital, leading the reader into its claustrophobic and oppressive space of “narrow bunks, low lights,” “the smell / of kerosene & lye,” the dormitory’s “pitched / dark roof & a high porch.” Through Brown’s evocation of material objects (dresses that become gags, rationed oil and milk), the reader becomes one of those with epilepsy or other disabilities who were imprisoned within the hospital or forced to labor on its grounds.

One of the book’s strongest sections, “In the Blind Room,” refers to the room used for solitary confinement. These painful poems are drenched in loneliness and desperation. Imagine a woman shivering in her slip, trying to find just a bit of light, telling herself:

It’s important to remember that once

you had a good life. Once you did not

know how to lie in a dark room,

your cheek pressed to the floor,

peering under the door frame, looking for the line of light.

These glimpses of life before the asylum make the experience of deprivation all the worse. However, even while reading of these horrors, we are drawn in by Brown’s diction, by her delicious repetition of letters and sounds: “life,” “lie,” “line,” “light.”

Not only does Brown engage all our senses—what we see, smell (“honeysuckle, horse manure”), and taste—but she also fills our mouths with frequent repeated vowels and consonants that give the poems sensuality and heft. These lines, for instance, from “Bird’s-Eye” illustrate Brown’s gift with sounds: “the girls returning in slow shifts from the farm; / their arms flung across each other’s shoulders.” Here, the sonic repetitions in “girls” and “return,” in “farm” and “arms,” in “girls,” “slow,” and “others,” reinforce the heaviness of the girls’ arms on each other’s shoulders and the heaviness of their work. These are real laboring girls, not phantoms.

The body is significant in these poems beyond the fact of incarceration. There are the terrors of seizures, when the body turns “animal in your / own throat.” Worse, there are sexual assaults in the blind room, in which, at any moment, a woman, her arms bound, might be “Down there in the blackness, held against the floor” while a man who is supposed to protect her admires her “fine face, / long legs, a scarless stomach,” the easy alliteration of those lines ironically juxtaposing the violation that they describe.

Brown also includes a devastating section about the forced sterilizations. The section is composed not only of poems but fictionalized medical orders for the sterilization of “idiotic,” “imbecile, “feebleminded,” and “epileptic” human beings who might give birth to “socially inadequate offspring.” These poems are tragic in their depiction of the ways that humans betray other humans, the “suddenly gentle” hands upon patients who crave touch, manipulating them into believing that they are fundamentally “wrong” and need fixing. The staff’s kindnesses are, in fact, a desecration of trust, an undoing, the act of “cleaving” somebody from their own body and future.

Besides the book’s necessary focus on corporeality, there is a great absence: God. While a nameless woman is being raped in “New Knowledge for the Dark,” she tells herself, “Think about your body. / Think about infinity. Think about God.” And it’s not clear whether the angel Gabriel, who suddenly appears in “The Blind Room: A Consecration,” is a messenger of hope or something more sinister, “swallowing the final stars.”

Rather than raging at God for not intervening to save the exploited—the question with which all serious Christian poetry grapples in some way—Brown saves her anger and pity for the humans who can’t make room for ill people and feel justified in treating them as “less than.” Implicit in lines like “we are a whole host of reasons / to stop believing in anything” (with its clever play on the meaning of “host” as the bread of the Eucharist) is the recognition that the failure of imagination and faith is not located in sick people themselves, but rather in others.

These “caregivers” fail to teach patients the Bible, send patients resentfully to chapel services and lock them in, baptize epileptic children only when it’s clear that they’ll live, and wish that God would “take [the patient] up and let her be the end of it.” It’s not God who has failed the inmates of the Virginia State Colony, but rather their families and those who work there, who have ceased to see Christ’s face in suffering people. The Virginia inmates are looked at, examined, and studied—but only as rotten specimens.

Brown’s poems are fragmented and scattered in form because the minds and lives of those she writes about are similarly broken. In her evocative, tightly controlled poetic lines, she reminds us of our human bonds to each other, and how easily they can be shattered.