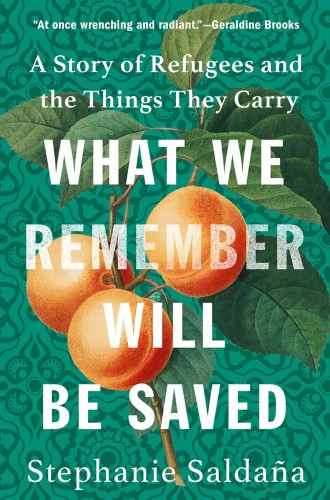

What do people who’ve lost everything bring with them?

Stephanie Saldaña reminds us that refugees carry a whole world inside them.

The question that Stephanie Saldaña poses in this book is a paradoxical one: What do people who’ve lost everything carry with them? She travels across the Middle East and Europe, going into war-torn places and in search of war-torn people, to ask them about what they’ve carried with them. The answers are not infrequently literal: a bar of soap that smells like home, a musical instrument, a kind of candy. But that isn’t really what Saldaña most wants to know.

Before we talk about remainders, Saldaña asks us to comprehend the loss. The UN has documented that every day an average of 44,000 people leave their homes due to conflict and persecution. The civil war in Syria, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the ongoing conflicts in Sudan, and the political situations in Eritrea, Iran, and Afghanistan have all contributed to this worldwide refugee crisis. Religions, languages, musical and literary traditions, architecture, and whole ways of life have been devastated. But sometimes you can only comprehend the loss by staring at the remainders.

Because of Saldaña’s own personal history—she is the author of two captivating memoirs about her life in the Middle East and how she came to learn Arabic—she focuses on the stories of refugees who fled conflict in Iraq and Syria, especially amid the catastrophic rise of ISIS in these regions and the effects of civil war. She goes in search of what refugees carried when they fled their homes.