A truth-telling child of Southern Methodism

Journalist John Archibald turns the spotlight on himself, his preacher father, and White Christians’ failures.

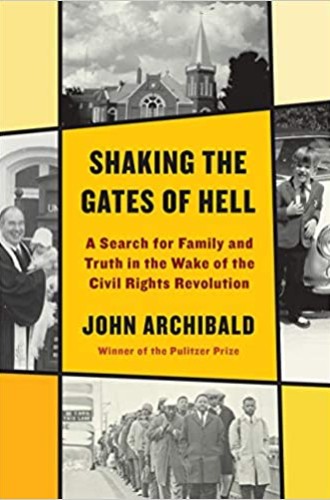

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist John Archibald has written an amazing book that’s a must-read for all preachers, if you dare. Ever the witty, incessant gadfly, Archibald’s reporting has led to the downfall of Alabama’s sleazy governor Robert Bentley, the exposure of corrupt utility companies, and the spotlighting of the horrendous human cost of bad local governance.

Now Archibald turns the spotlight on himself and his beloved Methodist preacher father, Bob. Sired by generations of pious, self-sacrificing Methodist preachers, John remembers his happy childhood at Methodist camp in the summer, family tenting trips all over creation as his dad introduced the kids to the wonders of nature, and his youth in a succession of sleepy Alabama towns where Bob served as preacher to the Methodists.

Bob was retired by the time I got to Alabama as bishop, but I immediately sought him out, so revered was his reputation for his loving pastoral work and for “doing the right thing” in the 1960s. When I was bishop, more than once I invited John to breakfast to give him my episcopal blessing after reading one of his courageous newspaper pieces, so proud was I that Alabama Methodism had produced such a truth-telling journalist. As it turns out, my church can’t take much credit for John’s truth telling.