Take & read: American religious history

New books that are shaping conversations about American religious history

Has it ever made sense to speak of the United States as a Christian nation or a “shining city on a hill”? Daniel T. Rodgers addresses this question in his insightful analysis of the text in which many locate the origin of the idea of a Christian America, John Winthrop’s “A Model of Christian Charity.” This 1630 sermon, supposedly delivered to Winthrop’s fellow Puritans during their voyage to Massachusetts, is the text in which the biblical phrase “a city on a hill” entered American history. In As a City on a Hill: The Story of American’s Most Famous Lay Sermon (Princeton University Press), Rodgers delves into the text, revealing that much of what we think we know about it is wrong.

There is little evidence that the message was delivered during the voyage, or even preached as a sermon at all. More importantly, the text merited little attention in US history until it was popularized by President Ronald Reagan amid a Cold War–era revival of interest in Puritanism. Rodgers also notes that most modern interpreters have fundamentally misunderstood the text. Rather than a triumphalist statement of American exceptionalism, Rodgers argues, the phrase was intended by Winthrop to be a word of caution, a warning of the risks of public failure.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Rodgers also draws a contrast between the Puritans’ humble communalism and today’s nationalistic capitalism. In an age marked by decreasing faith in the United States’ exemplary status in the world, Rodgers asks that we reexamine whether this self-image would have made any sense at all to the nation’s Puritan founders.

While Winthrop’s words have only recently gained prominence, Cassandra Yacovazzi’s Escaped Nuns: True Womanhood and the Campaign against Convents in Antebellum America (Oxford University Press) takes up a text that was both popular and influential in its own day and has remained so ever since: Maria Monk’s 1836 book Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk.

Purportedly written by an ex-nun, the book masqueraded as a sensational exposé of the sinister inner workings of convents. Unlike Winthrop’s sermon, this text was fake news from its very inception. Its true authors were male, and the events it detailed—infanticide and the torture and imprisonment of nuns by despotic, licentious priests—had no basis in fact. Despite its fraudulence, it resonated with many Protestant readers and helped spur a massive campaign against convents in the antebellum period.

At a time of increased Irish and German Catholic immigration to the US, many American Protestants were uneasy about these religious and ethnic others, an unease which was exacerbated by gender norms. Those who saw the wife and mother as the ideal woman were suspicious of women who had forsworn marriage and childbearing and placed themselves under the authority of unmarried men.

Monk’s book, along with others in the same genre, helped create an “anti-convent culture” which included investigations, persecutions, and mob violence. Despite common assumptions about mob violence, these anti-convent outbursts were not the work of an uneducated working class. In many cases, they were middle-class social reformers who were at the same time advocates for public schools and the abolition of slavery and prostitution. Such reformers, driven by concerns about industrialization and urbanization, sought to aid the poor, enslaved persons, and prostitutes—and nuns, whom they believed to be imprisoned, enslaved, and under the sexual control of priests.

Racial terror lynching, another form of mob violence inspired in part by baseless fears about sexual violence against women, has received recent attention due to the 2018 opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, which memorializes the victims of such lynchings. In At the Altar of Lynching: Burning Sam Hose in the American South (Cambridge University Press), Donald G. Mathews shows the extent to which many racial terror lynchings were connected to religion.

Lynching, Mathews argues, is not a marginal story. It is “an American institution” that fits especially well within a southern evangelical Protestant context that emphasized blood sacrifice, fiery judgment, and revivalist frenzy. Mathews examines white Christians’ practice of lynching as a ritual act, a sacrifice on behalf of whiteness that was enacted to restore balance to the social order in response to the perception of an alarming disruption of society.

Such disruptions took the form of criminal or unorthodox activities—occasionally real but usually imagined—of people of color. Mathews focuses on the 1899 Georgia lynching of Tom Wilkes, aka “Sam Hose,” at which one of the lynchers offered praise to God amid a kind of religious ecstasy. Religion was not the primary motivation for all lynching, Mathews argues, but southern Christianity made major contributions to the construction of a culture that made such lynching permissible or even required.

While the civil rights movement’s most famous episodes occurred in the 1960s under the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr., many scholars describe a “long civil rights movement” that began in the 1930s and continues beyond the 1960s. In The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age (Chicago Review Press), Patrick Parr broadens our knowledge of the civil rights movement by examining not the King of the 1960s South, but the King of the 1940s North.

In 1948, motivated in part by two infamous 1946 lynchings in his home state of Georgia, the 19-year-old King began his preparation for a career of pulpit-based racial justice activism by enrolling at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, located five miles north of the Mason-Dixon line. Parr offers a detailed account of King’s three-year seminary experience, including careful attention to each of his courses and professors. The book also examines King’s relationships at the time with his parents, siblings, fellow seminarians like Walter McCall, and mentors like J. Pius Barbour and Kenneth L. Smith.

Parr breaks new historical ground by locating and interviewing Betty Moitz, the white woman whom King met and nearly married during the Crozer years. In addition to providing insightful analysis into King’s relationship with Moitz, Parr traces the early formation of many of the ideas and attitudes King would later employ in his civil rights leadership.

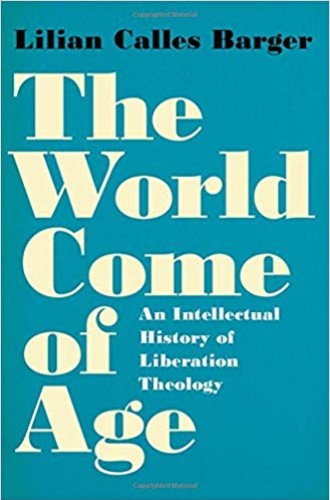

In The World Come of Age: An Intellectual History of Liberation Theology (Oxford University Press), Lilian Calles Barger calls us to attend more carefully to the common ideas, developed independently but simultaneously, of three major strands of liberation theology rooted in the Americas: Latin American, black, and feminist.

Barger provides a comprehensive history of the ideas that constituted early liberation theology. She examines each of these three liberationist strands, focusing on their common critique of the modernist separation of religion and politics. Together, liberationists created a hemispheric American theology, a “new orthodoxy” that ties oppressed groups together in a shared struggle, practicing a “religion from below” that springs forth from God’s identification with those who suffer.

Barger’s attention to this hemispheric context—including US imperialism—allows her to detail how liberation theology arose out of cultures known for their ideals of freedom and their lived practices of oppression. Barger’s work provides critical background for understanding contemporary religious demands for social justice that are based in particular contexts, yet intersectional and global in scope.