Social gospel heroes?

Janine Drake identifies ulterior motives in the church’s collaboration with labor in the early 20th century.

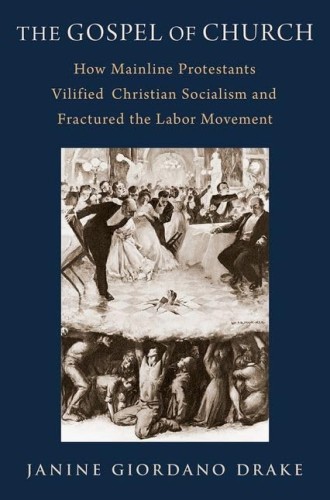

People are often the hero of their own story, but what happens when we try to make ourselves the hero of somebody else’s story? In her account of labor reform and Christian socialism in the early 20th-century United States, Janine Giordano Drake claims that this is precisely what the leaders of the social gospel movement did. While many progressive Christians today celebrate the history of the social gospel movement and its impact on labor reform, The Gospel of Church tells a different story, in which White Protestant ministers co-opted the moral authority of a diverse working class and took credit for the success of the labor movement. In taking over the narrative, these ministers did indeed succeed—not in achieving solidarity with wage workers, but in their goal to grow church numbers and “restore churches and church-based charities to that coveted role in American culture as the primary purveyors of education, health, and social services.”

Drake opens her argument in convincing fashion by immersing readers in the anxiety surrounding the relevancy of the church in the Gilded Age (1877–1900). Drawing on popular fiction of the time, she shows that the average American distrusted Protestant churches, believing they catered solely to the wealthy. While the working class celebrated the figure of Jesus the carpenter, they rejected “churchianity,” a term coined by minister and social gospel leader Charles Sheldon to satirize those who believed in the church more than Jesus. Rampant distrust in the church, combined with low attendance and the rise in popularity of socialism, left ministers scrambling to remain relevant. Drake finds it suspicious that at the height of socialism’s popularity, social gospel ministers formed the Federal Council of Churches, a union of 32 Protestant denominations committed to labor reform in partnership with the American Federation of Labor. Drake provokes readers to ask: Did the leaders of the social gospel movement really care about the daily conditions of workers, or did they primarily care about getting those workers through the doors of their churches?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Drake depicts the FCC’s work in labor reform as ultimately directed toward the goal of making the church relevant. This was evidenced most clearly in the FCC’s involvement with strike reports, in which members of the FCC would investigate labor conflicts, write up their findings, and offer recommendations to ameliorate the situation. The FCC’s recommendations typically emphasized the need for the church’s moral authority and advised companies to hire industrial chaplains to support workers and encourage them to attend a local church. For Drake, these reports indicate a move on the part of the FCC to take moral authority away from unions in order to “install white Protestants as the highest moral authorities.”

Through these reports, Drake shows, the FCC was able to attribute wins in labor reform to the church’s involvement in mediations and take credit for the hard work of union organizers. In narrating itself as the hero, the FCC succeeded in its goal of making the church relevant. It gained the ear of Woodrow Wilson and championed a vision of welfare capitalism as the way forward, ignoring the more radical demands of workers.

While Drake’s argument is persuasive, one wonders whether the leaders of the FCC and the social gospel movement are quite the villains she makes them out to be. It is hard, for example, to see how the FCC’s desire for church growth differed from the Social Democratic Party’s desire to grow its voter base. Each operated with the belief that its principles offered the most liberative path for workers. And both were led by privileged men whose voices became the loudest, and whose stance inevitably contradicted that of their members. Yet Drake portrays one as exploitative and the other as simply having “sometimes lost track of the priorities among their base.”

Moreover, some of the examples Drake highlights as evidence that the social gospel movement co-opted the authority of labor unions could warrant a different conclusion. This is seen most clearly in her chapter on Charles Stelzle’s Labor Temple, a Presbyterian church building in New York City that “offered union meeting space, free college courses, and public forums.” Drake argues that the Labor Temple served to make wage earners dependent on church resources. Rather than “defend[ing] the legitimacy of Christian Socialism as a Christian movement for positive social change,” the Labor Temple’s ministers stood against socialism and conceived of the many socialists who used their space as their mission field rather than representatives of their ministry.

In making this argument, Drake diverts attention from the fact that the Labor Temple opened its space to the Industrial Workers of the World, a radical union whose members were surprised to find how receptive the church was to their goals. It is no small fact that New York State repeatedly investigated the Labor Temple for sedition, showcasing the church’s openness toward union workers whose ideas competed with its own.

Nevertheless, Drake’s work offers a powerful reminder to leaders invested in Christian social reform today. Our desire for the church to be relevant can overshadow our efforts to listen to and amplify the voices of those with whom we express allyship. We can mistake church growth as the primary way to bring about justice. We can even mistake the church as the sole authority on what is best for all. In asking, “Why have American church leaders so long sought the responsibility of defining and managing social services on behalf of the republic?” Drake dares us to examine our motives and goals. Are we just trying to be the hero?