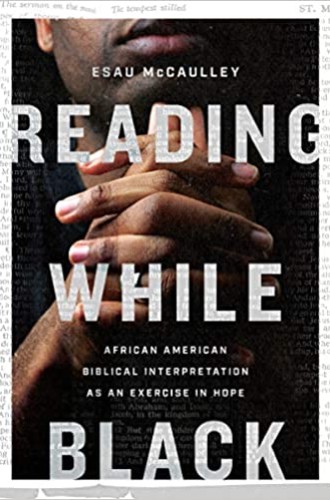

Seeing Black people in scripture

Esau McCaulley’s book reclaims what the Black church has always known.

What does it mean to exercise hope while reading the Bible? Esau McCaulley approaches this question through the perspectives and questions Black readers bring to the interpretation of scripture. Reading While Black is a much-needed addition to the shelves of hermeneutic resources available to preachers, students, and teachers. Its insights, although designed for Black readers, should be read by others as well.

As a military spouse who attended many events meant for the wives of soldiers, McCaulley learned that there are advantages to being the one man listening to the conversations in a room full of women. In this book, he offers a similar advantage to White readers: the chance to visit a majority Black space and see how Black people talk differently than they would if they were the minority in the room. For both insiders and outsiders to its conversations, Reading While Black opens up fresh ways of seeing ancient truth.

McCaulley, who is best known these days for his opinion articles in the New York Times, is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America. He teaches New Testament at Wheaton College, having studied under N. T. Wright at the University of St. Andrews. After his experiences at seminary, where, as he writes, “almost all the authors we read were white men,” McCaulley recognized the need for his book to fill a gap in the conversation. “It was as if all the important conversations about the Bible began when the Germans started to take the text apart,” he writes, and his evangelical professors seemed oblivious to the history of Black interpretation of scripture.