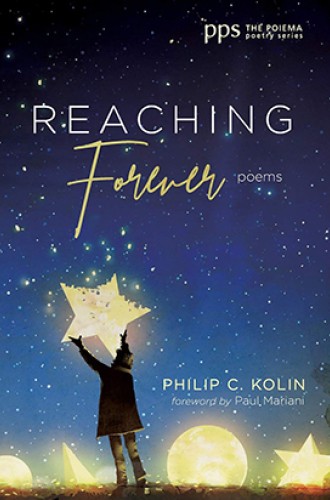

Philip Kolin’s poems for the holy, violent earth

Yearning for the impossible, glimpsing the unimaginable

Philip C. Kolin is that rare thing: a formidable scholar of literature who is also a poet. His poetry reveals another trait that’s rare in contemporary literature: intense integration of his strong Catholic faith with a world that he not only gazes upon but seizes—as both a gift and a puzzle to be pondered. In this singular collection, Kolin reveals deep knowledge of scripture, profound involvement in the conundrums of faith, a brilliant eye for unusual images, and a rare ear for language that praises and questions.

In these poems, nature is both sacred and sacramental. In “Autumnals,” a poem that first appeared in the Century, Kolin notes the resonances between the season of dwindling light and human life while observing that fish in a pond “create expanding circles, / their fins sleeking like angel wings, / a world yet to be.” In other poems he calls the autumn trees “sacred forestry” and “holy souls,” still fecund “even in old age.”

In spite of this infusion of the spirit in nature, Kolin does not flinch from speaking of the earth gone dark. He uses as a plangent metaphor the “black blizzard” of a dust storm, “dust begetting dust,” “our memories of green / splintered into brittle amnesia.” Fleeing “the bleak, black sun,” a family heads west toward Los Alamos, where “the clouds billowed like white mushrooms, / ready for the picking.” Escape is never really escape in an environment in which human energy is focused on destruction.

And nature, in a world of changing climate, is not kind. With a nod toward Lot’s wife, Kolin writes of a difficult southern winter:

Old men, mustaches marble-frozen,

dared the beach, mumbling

about this unseasonable season

while their wives kept looking

back at the Gulf for answers,

their sea-salt breath turned into

pillars of frost.

The poet’s musings on stories from scripture upend expectations as he discovers unusual angles of vision and offers original interpretations. In one poem, for example, Adam, after the Fall, “worries he will fall again.” In another poem, living water takes on new life:

A woman there was baggage with so many husbands

she forgot the taste of their touch.

But at the interview of her life, she drew

water from Jacob’s well slaking her thirst

by satisfying His.

In “Magdalen Redux,” Mary is surprised by the “amber fragrance of flowers” she finds when she returns to the empty tomb. Before she turns to find the risen Christ, she asks, “But who keeps a garden in a tomb?”

Kolin frequently anchors his readings of biblical stories in contemporary experience. In “Saving Sammy,” the poet links Samuel’s mother, Hannah, with an unwed mother looking for a place to leave her baby:

I must find a sheepfold to warm

and welcome him. But all the signs

point to police or fire stations

where blue uniformed nannies

promise to sew their lips shut—

no blame, no shame, no name—

but that’s no amnesty for my heartache.

. . . Protect him,

St. Anonymous, patron of unwombed mothers

and abandoned babies.

Creating significant echoes, this poem is followed in the collection by a poem spoken by a child whose unemployed mother left him in an orphanage where “the nun’s eyes swallowed us.”

Calling God the “Unknown Knower of Creation,” Kolin both affirms God’s existence and acknowledges that God’s self may be inscrutable. Linking Isaac and Christ, Kolin writes, “One son saved; another saves all sons /. . . . wood for a sacrifice / but with thorns this time for a crown.”

These poems are saturated with an earthly holiness that finds connections and solace in biblical story and promise. The poems about Joseph present a figure whose life was “an explosion of angels” but who says not a word recorded in scripture. In other poems, Kolin imagines that he reads Isaiah to his son and teaches him to sing the Psalms.

Kolin is, however, not reluctant to yearn for what is impossible this side of the grave. Mourning the violence in his birthplace, Chicago, he laments,

Chicago, city of childless mothers,

Christ weeps under your L tracksFor all those women whose breasts

will never again nurse a child.The birth canal has become

the gateway to death’s harbor.

The collection, which begins with the waters of baptism, Genesis, and the Mississippi, ends with meditations on death and its trappings. Once again, Kolin finds an unusual angle of vision. In “A Parable of Shoes” he insists that shoes are a sign that the wearers, like Adam, are condemned “to forage and fret / endlessly over the peat / of the lower firmament” and that “the world’s legacy / is a dead man’s shoes.”

In the final poem, Kolin cautions readers that God’s “voice is / an octave higher than silence” and God’s call will come in the “thick darkness.” “Till then / quiver your soul,” he advises, and “Don’t think about / being made in his image” because “You will only be looking / into a dark mirror.” That this leads to unimaginable beauty in the resurrection is not so much a concluding and triumphant cry; it’s more a hope emanating from a small, still voice.