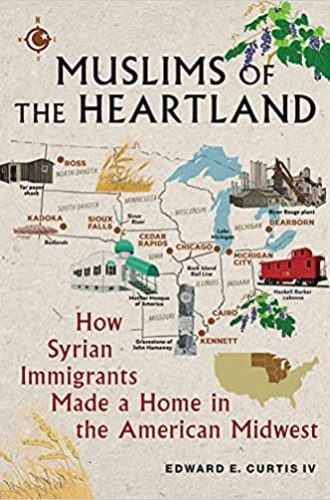

Ordinary American stories

Edward Curtis traces two successive generations of Syrian Muslims across small towns and cities in the Dakotas, Iowa, and Indiana.

Many Americans think of Islam as a religious and moral geography foreign to the American experiment, or at least to its foundational history. This is false, of course. Many of the enslaved West Africans who suffered the Middle Passage were devout Muslims, and Muslims can be found sprinkled throughout 18th- and 19th-century American history. Muslims from present-day Syria who moved to midwestern locales at the end of the great migrations of the 19th century have families who still make their homes in the Midwest. Edward Curtis offers valuable insights on this recent chapter in the story of Muslims in America.

Muslims of the Heartland traces two successive generations of Syrian Muslims across small towns and cities in the Dakotas, Iowa, and Indiana, from 1890 through World War II. Curtis gives readers glimpses into individual accounts—of farmers, peddlers, grocers, assembly line workers, soldiers, a gambler, a wrestler, and a poet—while also interweaving these stories with commentary on broader social, political, and economic trends.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In some ways, these are ordinary American stories. People struggle to hold on to the family farm while imbibing settler-colonial myths that befog the expropriation of land from Indigenous peoples. They manage small businesses during the Great Depression and form civil society institutions devoted to public charity. They establish ethnically focused religious congregations and sacrifice their children to wars. They experience marital successes and betrayals.

Curtis’s 40-year narrative provides a rich and varied account, however, of how these common challenges were met with the resilience of a distinctly Syrian and Muslim confidence. While he does not ignore the hardships brought about by American orientalism, racism, and religious discrimination, Curtis treats them with nuance and shows how people overcame them.

Orientalist stereotypes regarding violence and patriarchal brutality were common in newspaper articles in places like Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for example, and this had a corrosive effect on the lives of American Muslims. Yet such stereotyping, in Curtis’s account, was not thoroughgoing. News stories also often explained the significance of local Muslim rituals in appreciative ways, and Curtis cites the public appeals made by Sioux Falls civic leaders during World War I, which pushed back against anti-Muslim xenophobia and appealed to a sense of national unity that explicitly included Syrians.

Racially, Syrians existed at a complicated borderline and were subject to oscillating definitions of Whiteness in the late 1800s. While court cases like the 1915 Dow v. United States established them as White, the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act established explicit anti-Asian race-based immigration quotas that effectively closed the doors to most Syrian immigration. Such discrimination, of course, had significant impacts on the Syrian American community. How people ultimately were racialized by their community often had as much to do with their religiosity as with their physical presentation or nation of origin. Curtis cites one episode from the first decade of the 20th century in Michigan City, Indiana, for example, in which Syrian American Christians claimed Whiteness while excluding their Muslim expatriate counterparts.

Providing an accurate portrait of how the travails of discrimination coexisted with social harmonization—and the role religion played in that process—is a significant challenge, but Curtis is a skilled guide. Although theological belief isn’t a primary focus of the book, he seems to imply that many Muslims understood their own conception of the divine, in most important respects, to overlap with majority Christian views. Indeed, there are points in the narrative when one can glimpse a Muslim vision of the sacred that is as true to American civil religion as it is to anything else. Curtis claims that his subjects celebrated their ethnicity and religion as “pathways to becoming American” rather than seeing them as contrary to the gradual assimilation process.

Curtis’s own grandmother, for instance, suggests that one of the primary goals of Islam for American Muslims was to facilitate integration and produce “desirable, intelligent and law-abiding citizens” of their new country. He further recounts the story of Muhammad (Mike) Aossey, who often went to church with his European American Christian neighbors, seeing the experience both as a way to connect socially and a spiritual experience that didn’t betray his Muslim identity. “Mike seemed to believe in a universal God,” Curtis writes, “one that was as present for Christians as for Muslims.” After the church service, Mike “and his friends would go fishing at a nearby creek.”

Curtis writes with a polythetic sensibility about what Islam encompassed for the subjects of his study. There are charming accounts of Ramadan fasts, Eid feasts, communal prayers, and attempts (both successful and unsuccessful) to build centers for worship and community organizing. Ten fascinating pages are devoted to the early days of the Cedar Rapids mosque. Religious identity often (but not always) mattered for marriage and community relations. While outlining the socio-moral norms associated with laws pertaining to alcohol, veiling, and intermarriage, Curtis also makes clear that individuals understood and experienced these norms in very different ways, when they acknowledged them at all.

For all his skill as an academic historian, the most compelling parts of Curtis’s book are these personal stories—and he includes a few tantalizing snippets from his own story. Still, this book is not just about recording a history or sharing stories: its goal is to promote pluralism in Middle America. Curtis writes in the introduction: “Getting to know the stories of Syrian Muslims is an important step forward for those of us who want to cultivate the Midwest we desire—a heartland that loves all its people and loves us abundantly.” It is difficult to imagine the book finding readers who desire anything different by the time they reach its end.