Margaret Renkl’s stunning ability to see

It is hard to say what will enamor readers more, the bird calls or the familial ones.

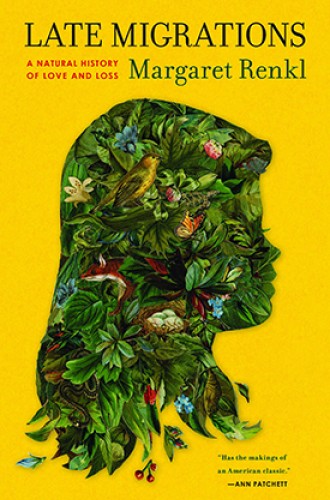

Nested within the splendid, Audubon-like illustrations of her brother Billy, Margaret Renkl’s poetic voice opens the soul. What begins unassumingly as a wee bit of meditative reading slowly lodges itself in the heart, spleen, and unexplored tender places. Then abrupt brutality intervenes: a starling hangs itself from the wire of the birdfeeder, a wild-eyed donkey stamps to its death in a burning barn, menacing men threaten violence at the edge of a peanut field, a cherished hatchling succumbs to a puncture wound to the head. And then there is refuge. The intermingling of family stories and natural wonder—like the act of holding out for solstice in the darkness, or Easter in Lent, or simply tomorrow in today—provides a resting place.

Late Migrations tells the truth. Sometimes it excoriates. Sometimes it miraculously transforms. Must beauty come at such cost? Renkl’s answer is yes.

Born into an Alabama family with a strong history of blindness, Renkl has a stunning ability to see. The ferocious lives of women in her family ring with a clarity that is lacking in the old, blurry, off-centered photographs she discovers. Babies are born in chamber pots, blue pills and electroshock therapy steal precious memories, children gradually learn that their mothers’ tears may not be their fault, and an enormous deadly attic fan haunts dreams in a way that will be understood by anyone who inhabited that dark, dire corner in a childhood home. A previously unpublished essay by Renkl’s grandmother lives in these pages alongside transcriptions of interviews, preserving the elegant cadence of a southern vernacular.