Literary faith from Dostoevsky to Marilynne Robinson

Poetry and fiction grant us glimpses of God.

I went to seminary because of a class I took on theology and literature. I’d studied history and theology, but it was reading fiction and poetry by Flannery O’Connor, Frederick Buechner, and Walker Percy that made me want to dive into the life of God and share God’s life with others.

It has surprised me since then how difficult it is to share literary insights as part of the life of the church. To quote a literary source in a sermon takes too much explanation. It often comes across as highbrow, pompous, or out of touch. The daring preacher who braves all those shoals and goes ahead with a literary vignette is likely to see it dissolve in her hands. It is difficult to write about other people’s writings about God and not sound like a crackling radio. Occasionally the gist comes through, but it’s hard to listen to.

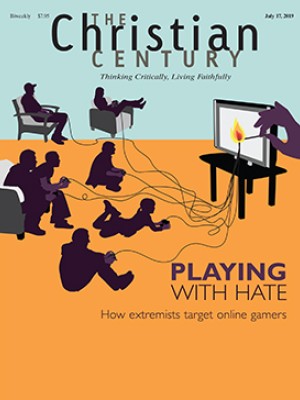

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Somehow Richard Harries has done better than this. The former bishop of Oxford in the Church of England has written a compilation of engagements with literary figures from Fyodor Dostoevsky to Marilynne Robinson, and every single chapter seems fresh and inviting. I learned about authors of whom I had never heard, and I learned new things about authors I’ve read backward and forward.

For example, I have waded into tracts of T. S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” and used a few of his lines (like “an alien people clutching their gods”), but I’d never known that he shocked his brother and sister-in-law during a trip to Rome when he came face to face with Michelangelo’s Pietà and fell to his knees. There is something profound about the great English literary mind and the greatest sculpture on earth interacting. I’ll never forget Harries’s description of Eliot’s perfect response.

I’ve also known something of W. H. Auden’s life of faith and have quoted his poems. But I didn’t know of his longtime relationship to a lover who was often unfaithful to him. Harries quotes a contemporary of Auden’s who describes speaking with the poet as his beloved flirted with other men. Auden carried on with small talk perfectly well, but a tear ran down his face. Somehow knowing that helps me care about the poetry more.

Perhaps I’d known that Dostoevsky was rejected by his fellow prisoners for being too aristocratic, even as he was desperate to learn from them about Christ. I’m certain I didn’t know that Gerard Manley Hopkins was convinced his work was dreck, even when he was in what is now regarded as his most fruitful literary period from which we all still benefit.

At times Harries overturns lazy clichés about this or that figure. Sure, Emily Dickinson was a sort of nun in the wrong century and faith, but she was no misanthrope—she loved the friends with whom she corresponded. Readers may assume that C. S. Lewis and Philip Pullman are polar opposites, the one a Christian apologist and the other an atheist culture warrior. Harries reveals deep similarities. And who can forget the report that Lewis would often challenge astonished visitors to his rooms to a swordfight?

One delight is to see Robinson elevated to the canon of crucial writers on faith. Harries describes her well as an angry opponent of all reductionism, a spinner of languid prose, and capable of great hilarity. (I had forgotten that John Ames’s grandfather was so committed to the way of Jesus that his wife had to hide their things to keep him from giving them away!)

As with any good compilation, this one will send the reader in search of some authors. For me, R. S. Thomas is the crucial next destination on the train. His poetry presents the sort of negative theology that our age so desperately needs. For Thomas, we never actually find God; we only find the place where God has just been, still warm with his presence. The resulting poetry is austere, difficult, a cleansing of cheap truths. Thomas was also a vicar of a church, and to hear a former parishioner tell it, one ill-suited to the job. (“Ay, I knew him, and a right miserable bugger he was.”) Perhaps poetry and fiction grant us glimpses of God that are only ever fleeting—a “twitch” on the fishing line, as Evelyn Waugh suggests, nothing permanently achieved.

Haunted by Christ could be criticized. There are not enough nonwhite or non-Western writers (Shusaku Endo will have to do here), and the subjects are slanted toward Anglo perspectives. But Harries knows what he knows; others can present treasures from other storehouses. And the book makes no pretense of comprehensiveness. It just seeks to be astonished at the beauty rendered indirectly through these stories and poems. I found my faith reinvigorated by it.

I have seen masters of preaching use poetry well, but many others quote too much and forget that poetry yields its fruits slowly, with rereading and sometimes misdirection, requiring patience and often technical aid. I had to forbid the use of poetry by my preaching students one semester, after noticing that whenever they turned to verse their sermons lost energy and sounded like caricature or satire.

It is an indictment that our ways of teaching poetry leave the impression that it is dull, and that somehow if you don’t know it, you can’t. Harries shows the opposite, and he makes me want to preach poetry again.