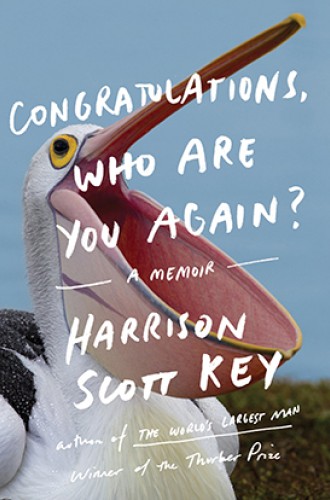

Harrison Scott Key’s 2015 memoir, The World’s Largest Man, is the funniest memoir I have ever read, surpassing even David Sedaris’s Me Talk Pretty One Day and Tina Fey’s Bossypants. It recounts a Mississippi childhood in which Key felt out of place in his home, particularly in relationship to his father, a “man better suited to living in a remote frontier wilderness of the nineteenth century than contemporary America, with all its progressive ideas, and paved roads, and lack of armed duels.” If Key already thought of himself as an outsider with respect to his family, his first book made his something of a pariah among lepers. But it also launched him into modest literary stardom.

His new book records the evolution of his dream to become a “great American writer.” Congratulations, Who Are You Again? could be marketed as a how-to guide—how to live a good life, how to write a good book, how to capture the American dream. Yet Key’s narrative overturns every impulse to read it as a step-by-step manual. It’s a book about chasing dreams, and yet the author repeatedly shows that we cannot write our own story.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The book begins with a quote from Cinderella, the model for all 21st-century dreamers who grew up watching the Disney film in which she sings, “A dream is a wish your heart makes.” Key reminds us that Cinderella “sings these words to a family of birds who wear kerchiefs and don’t appear to have the power of language, revealing the first important thing you need to know about dreamers, which is, most of them need psychiatric evaluation.” Dreaming seems crazy. But Key was raised in a generation that prizes dreams and the dream life above exercise of the “faithful presence,” to use James Davison Hunter’s phrase, or what Eugene Peterson calls the “long, slow obedience in the same direction.” Only after decades of dreaming does Key realize that the ordinary is often more beautiful than any pretense of the extraordinary.

His chapter “Prelude to an American Dream” begins with a hypothetical 19th- century immigrant’s lament: “I came to America because I heard the streets were paved with gold. When I got here, I learned three things: One, the streets were not paved with gold. Two, they were not paved at all. And three, it was going to be my job to pave them.”

Key writes about several types of dreams, from prophetic dreams like those of Martin Luther King Jr. to those where “you’re wearing nothing but a clerical collar and riding a dolphin through a grocery store.” He defines the American dream as “the answer of a calling to eschew the more common pursuits of personal peace and affluence in order to do something beautiful and exceedingly difficult with your life.” My ears perk up at this kind of language, which seems more Christian than uniquely American. A calling. Something beautiful. As difficult as the narrow way.

Key gives readers a vicarious look into his journey to “slight nominal fame,” starting with his first attempt at writing a sentence. “I was now a Great American Writer,” he writes hyperbolically, “and had an obligation to my vast imaginary readership to write a Great American Book.” In showing how subjective and limited dreams of fame are, Key demonstrates an enviable ability to distance his current reality from his former self, who viewed his dream and the enterprise to achieve it as all encompassing.

As Key sets out to become a great writer, he realizes the road ahead of him is unmarked. No one gives him tangible advice about how to become a writer or how to become famous. With each new job or each life step, such as marriage and fatherhood, Key learns more about fusing his ambition to the concrete particulars of reality. He is honest about the tension between the humble dreams of paying bills and keeping off welfare—“Wouldn’t that have made Jesus and my family happy enough?”—and the “desire to carve my name into history.”

At times, this urge felt and feels still, now, like that ancient terrifying lust of the human heart, which slays its brother and sets fire to villages. . . . At other times, the desire for greatness felt and feels like the great crowning glory of humankind, what we are designed for, to seize creation and make something new and beautiful with the raw stuff of it.

Is our desire for greatness a temptation to sin, a lust of the imagination? Or is it a vocation, an impulse to excel with the talents that God has given us? This book is a testimony to the impossibility of answering that question once and for all. Anyone who experiences ambition—with both its sinful and its virtuous aspects—must continually ask herself Key’s question.

Key is as wise as he is funny, overturning our cultural idioms to show the truth beneath them. While Cinderella pretends that dreams come true if you keep on believing, Key shows that dreams evolve more often than they are realized. His desire to be famous sent him on a road tour that gave him the runs. Meanwhile, the reality of fatherhood made him happier than signing autographs ever did. What he discovers, and what readers discover upon reading his journey, is that “no matter how great we hope to be, left to our own devices, we cannot build a tower to heaven. The tower always falls, no matter who builds it, the king or the fool.”