Edwards for all of us

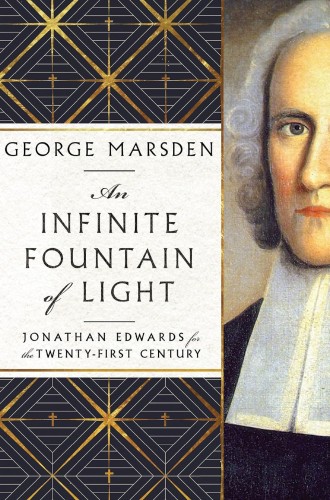

George Marsden’s new book returns to the old project of making Jonathan Edwards modern.

The modern revival of interest in the Puritan pastor-philosopher Jonathan Edwards began with historian Perry Miller’s 1949 biography. In Miller’s telling, Edwards was a solitary genius in the wilderness. While still a teenager, he was the only American to read and comprehend the revolutionary insights of John Locke and Isaac Newton. Edwards’s understanding of human psychology was so ahead of its time that, Miller claimed, “it would have taken him about an hour’s reading in William James, and two hours in Freud, to catch up completely.”

Miller believed that Edwards represented the antithesis of an American tradition best typified by his contemporary Benjamin Franklin. Where Franklin represented the optimism, rationalism, and commercialism of American modernity, Miller reclaimed Edwards as a prophet of a starker modernism, more aware of evil and devoted to deeper spiritual values than those of the marketplace.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

George Marsden is perhaps the foremost student of Edwards since Miller. His 2003 Bancroft Prize–winning Jonathan Edwards: A Life stood at the crest of several generations of scholarship that systematically overturned many of Miller’s conclusions. Where Miller had seen Edwards as a herald of 20th-century modernity, Marsden and these other scholars saw him as a man of his day. Edwards was not, it turned out, the only American student of Locke; anyway, his thought more closely resembled that of Cartesian rationalists such as Nicolas Malebranche. He was a passionate student of the Bible and especially biblical prophecy. Marsden’s biography brilliantly synthesizes these novel insights and paints a compelling portrait of Edwards as an American Augustine.

Given his role in defining the historical Edwards, it may come as a surprise that Marsden’s newest book returns to the old project of making Edwards modern. Marsden claims that Edwards is badly in need of translators who can offer readers “the best of Edwards’s insights that are most helpful today.” While Miller sought to make Edwards usable for disenchanted postwar intellectuals, opening up the possibility of “Atheists for Edwards,” Marsden’s aim is somewhat more modest: he hopes that Edwards might provide intellectual resources for Christians across “that transdenominational heritage that C. S. Lewis called ‘mere Christianity.’” In other words, Marsden’s goal is to present Edwards as a major theologian who can speak not only to the conservative evangelicals who have taken him up in recent years but to all Christians more or less in the mainstream of orthodoxy.

To make his case, Marsden returns to that most familiar of tropes in Edwards scholarship: the comparison with Benjamin Franklin. Historians have been unable to resist putting Edwards and Franklin in conversation with one another, though the two never met in their lifetimes. In An Infinite Fountain of Light, Marsden recapitulates Miller’s claim that modern, secular America is a sort of superficial wasteland. Drawing on the standard panoply of communitarian and anti-modern intellectuals (including Charles Taylor, Jacques Ellul, Christopher Lasch, and Wendell Berry), Marsden argues that

our civilization today is much more like the future that Franklin imagined than it is like that which Edwards predicted and hoped for. Many of the most basic motifs of our culture today, not just in the United States but also throughout much of the world, can be seen as the pervasive overgrowth from seeds that Franklin and allies were planting in the eighteenth century: ever-increasing technology; aggressive market capitalism; celebrations of self; trying to balance liberty and equality, materialism, permissive sensuality, nationalism, and transnational consciousness—just to mention a few.

Franklin’s America, then, entails the “virtual worship of the self,” a hyper-individualism which, abetted by technology and digital media run amok, “often reinforce[s] tribalism, exclusive identities, or superficial communities.” All of this leads to the situation that Taylor diagnoses as modernity’s “immanent frame,” in which we are utterly “cut off from a sense of the transcendent.”

Edwards provides the alternative. Although most general readers know Edwards only as the preacher of the fire-and-brimstone revival sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” Marsden joins the chorus of other recent Edwards scholars who recognize that sermon as atypical and instead direct attention to Edwards’s grandiose system of metaphysical theology, in which the firsthand experience of divine beauty and love stand at the center. Edwards’s universe, unlike that of 18th-century materialism, is dynamic, personal, and relational. As Marsden puts it, “In contrast to the materialistic pragmatic understandings that have been the default outlooks for so many in the modern world, the moral beauty of God, the beauty of perfect love manifested in Christ’s sacrificial love, is at the heart of Edwards’s vision of reality.” Creation, for Edwards, is not a onetime act but a continual process in which God’s trinitarian love upholds the world in every moment. The universe, then, far from being dead matter, is “a personal expression of the exploding or overflowing love of the loving triune God.”

Marsden writes that Edwards’s favored metaphor for describing the “ever-flowing beauty of God’s love and joy is a fountain of light.” He highlights the 1733 sermon “A Divine and Supernatural Light,” in which Edwards argues that the essence of Christian life lies in the immediate reception of a new spiritual sense capable of perceiving the beauty of the Divine. Marsden rightly notes the overwhelmingly aesthetic nature of Edwards’s theology but shows that in Edwards’s thought, living in the presence of beauty is not merely an otherworldly mysticism. God’s beauty, that infinite fountain of light, is an “active beauty, or a beauty that shapes our actions. As the sun is to the earth, the beauty of God’s atoning love in Christ is the great dynamo that generates Christian action.” For Edwards, Christian action is to be manifested primarily in self-sacrificial love toward the poor.

The weakest part of Marsden’s book is the chapter in which the archrevivalist George Whitefield stands in as a forerunner of some of the aberrations of modern evangelicalism. Here Whitefield emerges as a sort of Christian Franklin, attuned to the marketplace and emphasizing a potentially anarchic form of individualism. Whitefield—whom Marsden admires more than his descendants—pioneered a religious populism in which “the evangelists who succeed best are those who can attract the largest audiences and then build their own empires, usually offering simplified brands of the gospel that focus on a few compelling points with wide appeal.”

And yet, in his critiques of conservative and populist evangelicalism, Marsden keeps the gloves on. Not a single criticism is left unqualified. But Marsden’s charity toward the evangelical tradition is not extended to those Christians he considers “liberal,” whose “gospel has been limited largely to therapeutic and sentimental themes.” Such stereotyped digs at the Protestant mainline undermine the ecumenical intentions of Marsden’s book.

The question that Marsden’s book poses is whether Edwards’s vision really can offer an alternative to liberal capitalist modernity that may be appropriated by Christians of any stripe. The answer, I think, is yes. Edwards’s elevation of aesthetics—the dynamic experience of created beauty—in theology, his relational metaphysics, his uncompromising version of Christian charity to the disenfranchised and the poor, are not the property of conservative evangelicals alone. That infinite fountain of light is available to all with eyes to see.