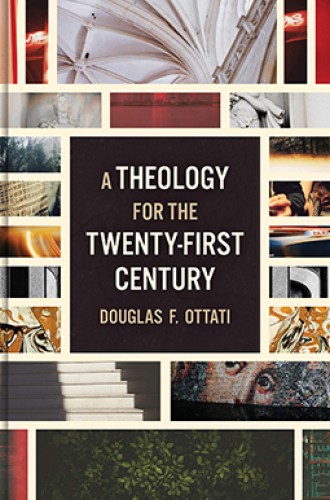

Douglas Ottati’s liberal piety

The theologian starts by recognizing that we know enough to live fully in response to God’s grace.

Twenty-first-century Christians might feel that “Christian believing is deeply problematic,” writes Douglas Ottati. Theology, he says, should not provide soothing, ready-made truths. Instead, he seeks to “identify the task at hand” and respond with “good theology.” He succeeds.

Ottati’s thoughtful discussions of Augustinian, Protestant, and liberal wellsprings intersect with scientific evidence, culture, and Christian practice. Christian humanism is the result. Ottati defines a specifically Christian piety: a “reflective, capacious, and compassionate” practice, lived in relationship with God the creator and redeemer. Though intellectually sophisticated, this book will richly inform pastors and Christian leaders as well as academic theologians.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

He begins by defining method as inclusive of both thinking theologically and living the Christian life. Augustine, he believes, modeled a distinctive biblical and intellectual approach to piety that’s unparalleled in its grasp of faith and life. Protestantism recovered Augustinian insights, freshly infusing Western culture with biblical motifs that would serve as groundwork for later Christian personalities. Ottati defines liberalism by its engagement with science, commitment to evidence, and fearless criticism of sources. He relies on approaches developed by great liberals, their theological progeny, and myriad others. The effect is quite wonderful.

Ottati continues his dance with theological giants in his discussion of creation and the creator-redeemer God. He believes that Albrecht Ritschl and Karl Barth both overstate creation’s value for human life, an act of “misproportioned theologizing.” Seeing the cosmos as creation reveals its simultaneously precious and precarious nature. A lovely exegetical discussion of Genesis 1–2 leads Ottati to reflect on the world as habitat, ecosystem, and universe in terms of cosmic ecology. With a sense of mystery, interdependency, and vastness, this reflection culminates in a “distinctive role for humans.” For Ottati, the point is ethical and spiritual: we are uniquely equipped and responsible for care of the created order.

God is the sustainer of all things, Ottati claims, in dialogue with the Reformed tradition and others, including Karl Marx and Charles Darwin. He offers a clear-sighted way to understand and live in light of the concept of providence. He also reminds us that our understanding is limited. Creation’s mystery and “cosmic passage” suggest we should maintain a “pious agnosticism” and not overstate claims about what God is doing. The focus is on what we should be doing. This treatment of the redeemed life accents human social well-being.

The final section of the book addresses the redemption Jesus brings through his life, death, and resurrection and the ongoing spiritual life offered by the church. Jesus Christ is the self-revelation of the God of grace who renews human life and social well-being in a fraught and dangerous world, in a cosmos beyond our comprehension. Tillich was right when he wrote that “Christ represents essential humanity.”

Ottati’s approach here, as elsewhere, argues against claiming certainty. A focus on practical wisdom requires relinquishing elements of “Chalcedon’s more speculative language.” Ottati further argues that “we have no unfiltered or direct access to what Jesus says, does, and endures.” We know enough to live fully in response to God’s grace.

Ottati’s refusal to define premature certainties allows him to think inclusively, making allies where some see enemies. This approach allows him, for example, to bring liberationists, feminists, and womanists into dialogue with liberals and others to rethink classical theological concerns such as atonement and the kingdom of God.

Notably, Ottati’s writing style aligns to his concept of God. He’s no milquetoast: he criticizes Augustine’s theory of depravity’s transmission as “exegetically far-fetched,” rebukes Luther for his anti-Judaic diatribes, and views Calvin as overly harsh on predestination. At the same time, he responds with a light and generous touch. His gentle, inclusive, and capacious mind stands in stark contrast to the shrill denunciations that have become so common. This approach to theology functions as a subversive judgment of hatred and illiberalism.

Ottati’s liberalism is a form of piety, not partisanship. He engages the biblical narrative, classical theological resources, and ecclesial practices with enough attention to provoke some liberals. He advocates hopeful realism, not winking at evil, and therefore stands against resurgent tribalism, insularity, and bigotry. The church is in, with, and for the world, but also against it. Its inclusive and humanistic impulses, for Ottati, commend liberal politics and care for all people.

I recommend this book for liberals and nonliberals alike. Will this kind of thinking be enough? Will churches and religious groups see the essentially inclusive nature of God’s love? And will those who hope for a compassionate world prevent the resurgence of destructive forces? We cannot be sure. But Ottati offers a significant, distinctively Christian way of understanding and undertaking these urgent tasks.