Do millennials bring something new to leadership?

Three authors, one Jewish, one Muslim, and one Christian, place their hope firmly in a new generation—again.

This is an odd little book. Its title notwithstanding, it deals with millennials on barely a half dozen of its pages. At its core, as the subtitle indicates, it is a leadership book which uses a biblical character to illustrate the principles the authors wish to teach. As such, it is a perfectly fine specimen.

What makes this book of particular interest among leadership books is its interfaith authorship. The authors—a rabbi, a Muslim scholar, and an Episcopal deacon—evidence a hearty appreciation for the character of Moses and the biblical narrative that tells his story. Mordecai Schreiber and Iqbal Unus also introduce texts from their traditions that developed from the biblical account. Thoughtful insights (and humorous asides) abound in their discussions of these texts, and the authors’ enthusiasm for them will surely spread to their readers.

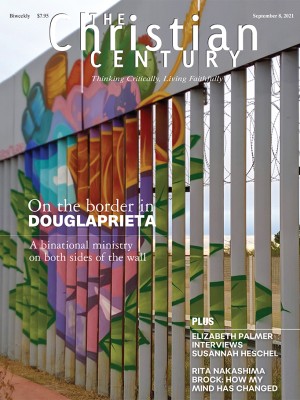

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Regrettably, the final text does not offer much in the way of interactions among the authors. No doubt all three learned much from one another in the process of writing the book, but readers are left without a sense of how each author’s thinking developed as a result of their shared study of this fascinating character. Surely this thin volume, even padded as it is with frequent sidebars, had room for the authors to model the kind of open and relational communication they commend.

While the leadership principles on offer are not new, they are solid. They are, for the most part, presented in harmony with the texts discussed. As is inevitably the case with this sort of project, some connections are tighter than others, and readers familiar with the biblical narrative will be sure to find some of the authors’ interpretive moves a little too slick. But it is the rare book of this type—C. K. Robertson’s Barnabas vs. Paul comes to mind as an exceptional example—that is exegetically unassailable.

What, then, of the millennials, the generation on whom the authors (or whoever titled the book) have set their hope? The authors believe that “the future will go to those who understand that a period of great reconciliation and providence is possible by new leaders who will put people over politics.” By following the example of Moses, they argue, a rising generation of leaders exercising humility and servant leadership will save us from “a seemingly endless cycle of hatred and violence.”

All well and good. But the authors fail to demonstrate why anything other than the accidents of history (the time when millennials are rising to leadership roles, for instance, and the sheer size of the cohort) justifies their hope that millennials will rise to the unique leadership challenges our society faces today. Most of the qualities they ascribe to millennials—seeking work with meaning, disliking authoritarian leadership, preferring to be listened to rather than ignored, wanting to be led by people they respect—really are not peculiar to this generation.

If anything, the qualities the authors ascribe to millennials should be recognized as those common to young adults of any generation. As Generation Z graduates from college, its members, too, will “want to be able to set their own schedule and work hours.” Members of my own Generation X “deeply resent[ed] being stereotyped with overly broad descriptors” when we were the objects of ’90s-era pop sociology.

In truth, the generation ostensibly in focus in this book serves more than anything else as a locus for the projection of the boomer authors’ ideals of their own generation. The last few years have given us countless 50-year retrospectives of a time when “the whole world [was] in a polarizing period caught between a younger generation that prefers peace and collaboration, and demands its voice be heard, on one end, and aging autocratic leaders and old-fashioned tyrants who attempt to keep power centralized to themselves, on the other.”

But time turns every young idealist old, and hard experience usually makes them a lot less idealistic. And those who yearn to seize power from those they believe are misusing it will inevitably find themselves subject to the same accusation. Sometimes the accusations are unjust; then there are the other times.

Lacking a bibliography (let alone adequate citation of sources), this book would not be suitable for use in a classroom setting, except perhaps as a cultural artifact. Not all of the asides are humorous, gratuitous political jabs abound, and Shakespeare is both misquoted and improperly cited. These critiques notwithstanding, the book could provide useful fodder for group discussion and would be especially suitable for interfaith book groups.