A dinner party where women talk food

Alissa Wilkinson imagines Maya Angelou hosting Hannah Arendt, Octavia Butler, Laurie Colwin, and others.

It’s a familiar party game: imagine your ideal dinner party. Invite anyone, living or dead. Who would you bring to the table? Alissa Wilkinson gathers together a group of vital 20th-century women, mostly Americans, who have participated in changing the way our culture thinks about food and community. Her idiosyncratic experiment in biography through food makes for delightful reading. “A dinner party,” she writes, “creates a universe.”

The women she invites aren’t all obvious choices, nor are they all connected to food in obvious ways. Hannah Arendt was not exactly known as a food writer. Octavia Butler, the mother of Afrofuturism, lived an extremely frugal life in order to prioritize her writing. Her idea of a feast was the Pasadena Public Library, where she spent hours doing what she called “grazing.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

At Wilkinson’s dinner party, Butler sits perhaps somewhat shyly next to Elizabeth David, a British writer who, because she couldn’t actually buy a tomato in postwar England, began the transformation of British home cooking through her imagination. She was in a hotel in Ross-on-Wye when, “hardly knowing what [she] was doing,” she took a piece of paper and began to gather her memories of better times and better places and, especially, better food.

There’s southern food writer Edna Lewis, sitting next to Parisian maven Alice B. Toklas. Laurie Colwin, whose book Home Cooking has served as great comfort to homebodies who like mayonnaise, is accompanied by Maya Angelou, who deftly connects food and memory at every turn—and they are joined by the great lover of the cinematic potato, Agnès Varda.

All of these women find a common language over love of food. In other words, this is an eclectic group, and like at any great dinner party, the conversation is rich but also at times awkward. For example, does Arendt ask Toklas about her support for the Vichy government in France? Does Butler chide Angelou for the relentless optimism in her work, which in Butler’s is harder and more brutally won? We can imagine, but we can’t know.

Wilkinson sketches out each chapter with a short biography of the woman who is its subject and an engagement with her writing. The relationship to food and drink can sometimes feel tangential. Ella Baker was a kitchen-table activist but not really a cook. “She didn’t keep much food at her apartment in Harlem,” Wilkinson writes, “and more often found herself eating at the tables of others, listening to them, hearing what they were thinking and needing.”

But Baker was obsessed with creating the conditions for equality in a segregated society. She followed a philosophy of enacting change: embodying the new reality before it was shared. And this happened, not incidentally, in places where people gathered around food. Wilkinson notes the importance in the civil rights movement of sit-ins at sandwich counters. When the students sat down at these counters, they physically embodied—at great risk to themselves—a more shared and equitable future.

This is the kind of broad invitation that Wilkinson offers. You don’t have to be a great cook to come to this party. You don’t even have to like food. Consider Arendt, who threw great cocktail parties but spent no time in her prolific writing on food itself. For her, the conversation was the feast.

Wilkinson offers a recipe at the end of each chapter, and these are astute on two levels. First of all, these recipes are well-made, readable, and accessible. Second of all, they are playfully and creatively related to the woman whose life the chapter is about. Butler’s story is paired with a vegetable stew that is loosely derived from a passage in Dawn in which aliens try to imagine what humans like to eat. The final chapter on Angelou—the dinner party’s imagined host and presider—is paired with pears in port wine, Angelou’s favorite dessert. Baker settles in with her friend Odette Harper Hines for a Louisiana-style shrimp salad.

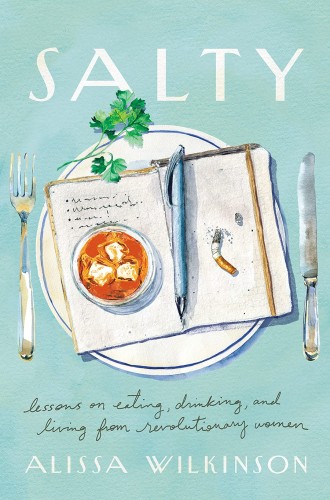

Wilkinson wrote Salty somewhat wistfully during the pandemic, when hosting and being hosted were mostly memories and the idea of gathering people around a table seemed more dangerous than sagacious. The book makes a strong case for resisting the individualism and isolation toward which the pandemic pushed us and returning to community, connection, and love-fueled gatherings. This is what we do, Salty insists, as humans: we gather, we share food, we remake the world.

Wilkinson’s book is convincingly delicious. It will make you want to cook—or at least to think about the food you love and why you love it, the company you love and why you love it, and the meaning of the feast in your own life.