A city dweller follows the harvest

Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s spiritual and cultural pilgrimage through the heart of farm country

One hundred years ago, my grandfather left his home in Ohio to follow the Kansas wheat harvest. For restless Amish youth like him, joining a harvest crew promised a jot of adventure and tittle of cash, all within the safety of their known rural world.

To “follow the harvest” sounds implicitly spiritual. It’s as if the land, like Jesus, sets the agenda. It’s as if men with machines are under the thrall of grain—which, of course, they are. From my grandfather’s team with its horse-drawn threshers to custom harvesters today with their half-million-dollar combines, harvest crews begin their patronage in the south and crawl slowly northward as fields ripen. Geography and weather make it clear that the farmer is a disciple of the field, not the other way around.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

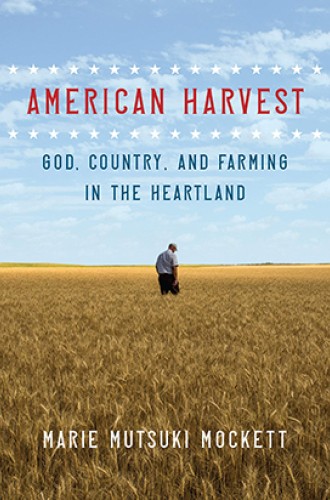

“Joining a crew” sounds faintly theological too, as we also speak of joining the faith, joining a church, joining ourselves to God. So when writer Marie Mutsuki Mockett joins a crew that follows the harvest, it is fitting that religious themes fill the pages of her memoir. American Harvest is a sprawling story of pilgrimage, spiritual and personal and cultural, and Mockett’s gaze is both penetrating and sweeping. She reports on everything from the religion to the culture to the history to the geology that together form the Great Plains. As my mother would say, she doesn’t miss a thing.

Mockett embeds herself with a team of mostly men and a few women who travel from Texas to Idaho with their equipment, including three combines, loaded onto four semitrucks. Along the way Mockett, who has lived a mostly bicoastal urban life, confronts her stereotypes of farm folk even as she forces them to confront their own stereotypes. She reckons with the fact that things she had viewed as either delightfully or annoyingly out-of-date—fields, tractors, God—are actually essential. “Even in the city, people have to eat, and my idea that growing food is an old-fashioned occupation is unrealistic,” she writes. “And when I think this, the idea that God is necessarily old-fashioned also starts to fall apart.”

Mockett brings a unique insider-outsider perspective to her subject. Her father’s family owned a 7,000-acre farm spread between Nebraska and Colorado, and she spent time there as a child with her grandparents. But her white father and Japanese mother raised her in California, and she was educated on the East Coast. She has also spent time in Japan, where her family owns and runs a Buddhist temple. The heartland of her book’s subtitle occupies little of her attention until her father dies and she inherits his portion of the farm. Then she begins a deeper inquiry into the chessboard landscape of so-called flyover country and the people moving about in it—people who, to her friends in cities, resemble pawns: smallish, irrelevant, and, judging from the results of the 2016 election, easily duped.

So when Eric Wolgemuth—a “conservative farmer,” as the book’s marketing copy calls him, who has harvested her family’s wheat for more than 15 years—invites her to travel along with his harvest crew to learn about what he calls “the divide,” she agrees. Mockett frames her journey in part as an attempt to answer a question that stumped her: why her city-dwelling friends, who are mostly atheists, were so against GMOs and so enamored of organic food, while the midwestern farmers she’d met, who were Christians, were so willing to tout the benefits of GMOs. Wouldn’t belief in evolutionary processes lead the first group to accept the human interventions of genetic modification and synthetic fertilizer, and belief in a sovereign and creative God lead the second to reject them?

When she poses the question to Wolgemuth, he suggests that she join his family and their crew—less to find an answer to her question than to “share his America because he feared how little we have come to understand each other,” she writes. “The divide between city and country, once just a crack in the dirt, was now a chasm into which objects, people, grace and love all fell and disappeared.”

Mockett’s prose is winsome like that, and lyrical enough to garner endorsements from Annie Dillard and Ian Frazier, the latter of whom says she writes with “openness and bravery.” Posing questions about race, religion, and science in Trump’s America—and doing it in a region where few look like her and every day means manual labor—requires courage of both intellect and body.

The other truly brave person in Mockett’s account is Wolgemuth, her host, who seems unfazed by the very public nature of the portrait she will paint. He answers her questions with no apparent defensiveness or desire to impress, although members of his harvest crew are uncomfortable with the access he grants her to their daily lives. Whether it’s her race, her gender, her liberal, educated, and urban sensibilities, her admitted ineptness at farming, her status as absentee landowner, the fact that she isn’t a Christian, or the fact that she is writing a book in which they will appear as characters—whatever the reason, in Mockett’s presence the harvest crew becomes increasingly more divided, their conflict apparently rooted in how to handle this outsider.

Their hired help aside, it would be hard to find more likable and sympathetic interpreters of rural American Christianity than Wolgemuth and his son Juston. Neither neatly fits the red-state stereotype evoked by the publisher’s “conservative farmer” description. They live in Pennsylvania and are members of a small Anabaptist denomination, the Brethren in Christ, which puts them at both a geographical and theological distance from the evangelical churches they visit along their route. And as Mockett discovers in her conversations with Wolgemuth, he is not a young-earth creationist, nor a Trump supporter, nor a gay-bashing fundamentalist. He is a “Jesus guy,” to quote Juston, who is an English major, a reader of Rob Bell, and a fan of The Liturgists podcast.

The Wolgemuths start out each day with the crew reading scripture, and Eric refuses to harvest on Sundays. Eric is also an inquisitive soul—“eager, as always, to apprehend something new about the world and how it works” and happy to talk about any topic his guest raises. Together, Eric and Juston engage in wide-ranging conversations with Mockett about free will, coyotes, Revelation, no-till farming, the politics of food, and evolution. They’re as keen to learn about her side of the divide as they are to teach her about theirs.

They also help her experience a cross-section of rural Christian congregations, from a cowboy church in Texas to a Mennonite church in Oklahoma to a house church and an Evangelical Free congregation in Nebraska. The crew is in Idaho when the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville turns deadly, and Mockett wonders aloud to Juston if the church they visit the next day will mourn the violence of white supremacy. “They won’t say anything,” Juston tells her bitterly. He’s right; they don’t.

American Harvest is sure to wield authority in election-year conversations about what the place named in Mockett’s subtitle—heartland—signifies. It is a contested term, even more so since Pete Buttigieg unwittingly unleashed a Twitterstorm as powerful as the storms that roil across a Kansas sky by claiming that the next president’s vision should be “shaped by the American Heartland.” The criticism, which noted that heartland is simply code for white, was torrential. “Respectfully, where is the American Heartland located exactly in your mind as you write this tweet?” filmmaker Ava DuVernay tweeted. “Does it include Compton and other places like it? Because us folks from those places would like a president shaped by our vision too.” “I grew up in the so-called heartland,” tweeted NPR reporter Michele Norris—“Land of casseroles and county fairs and Friday night bingo. And yet it seems that term does not encompass the neighborhoods where I lived and the folk of the great migration that raised me.”

The nostalgic white gaze at rurality is real, even for progressives, and this book’s sales may benefit from it. Yet shaped as it is by a life lived in liminal spaces, American Harvest offers a distinctive treatment of the great divide her project tries to bridge. Mockett seeks out other people of color along the harvest route. Other than some Shoshone people at a sun dance and Vietnamese women at a nail salon, she has trouble finding them.

She does have a disturbing conversation with Sally, a Native American Mormon, who construes the seizure of land by white settlers as God having “allowed the land to be taken because we were no longer a righteous people.” In response, Mockett is speechless. “The architecture of this world feels to me like a psychological prison,” she writes. “They have thought of everything, these people who have created this world.”

With whiteness in full bloom around her, and weary of feeling like the source of conflict among the hired harvesters, Mockett cuts short her journey with the harvest crew. She is exhausted by trying to “erase parts of myself that look out of place so that everyone else will feel at ease.” A divide is hard to cross when erasure is required.

Economic class enters her story less than one might expect. Mockett’s most substantive interactions are with other landowners. And she doesn’t delve into the issue of absentee ownership of midwestern farmland until more than halfway through the book, when she and the crew have made it to Kimball, Nebraska, where her grandparents lived. There she encounters Karen, a woman who tells her about the town’s declining population. “So many houses have been abandoned. The town is so full of empty houses,” Karen tells her. “And there are so many absentee farmers.”

“That’s me,” Mockett thinks to herself. “I am an absentee farmer. I am pretending to be a farmer, though I live somewhere else.” Mockett has mentioned her family’s relationship to the land, but not until this moment does she consider that their narrative might not be an isolated one. Even then Mockett’s touch is light, as though she can’t bring herself to mull the ways that her own narrative is connected to the emptying out of the midsection of the country. (According to the USDA, 41 percent of Iowa’s farmland and 50 percent of Illinois’s are now owned by nonresident nonfarmers.)

The author proves herself an attentive observer of the land itself, though. The passages in which she describes the landscape of the wheat belt seem to contain her truest voice. “When it isn’t raining, you feel a quiet and persistent sentience,” she writes in the book’s prologue. “All around you, things are growing. . . . The smallest elements are in perpetual motion, always creating or decaying, directed by some invisible force. Perhaps that is why it is so easy here to feel that God exists, and that he inspires awe.”

Mockett is also an adroit observer of Christianity. Having grown up in an irreligious household, she sometimes stumbles over the nuances of the ecclesial landscape. Yet her distance from the clichés of Christendom may lend her more grace than she’d have if her friends weren’t all atheists. “I had not expected to have a meaningful experience of the Gospels and of Jesus,” she muses to Wolgemuth toward the end of the book. “Maybe you’re a Christian,” he tells her. She neither argues nor confirms, and he doesn’t push the point.

His wife, Emily, is more forward. “I will pray for you,” she calls to Mockett as she climbs into her rental car to go home, “and pray that you will find Jesus!”

Mockett has been on a pilgrimage of sorts, and Emily is right to recognize it. I go to church with kind and earnest women like Emily, and I can even identify with her longing: that the restless will find their rest in Christ. Yet I flinch at these parting words, which seem to render the entirety of Mockett’s sojourn as spiritual in nature. To press the undulating terrain of her literary project into a personal search for a Savior is to flatten it into a single dimension.

Then again, for women and men closer to the harvest than I am, Emily’s words—pray, find, Jesus—likely sound less like religious pablum and more like the hearty staples of a true faith. To them, the Christ we find and follow is akin to the grain they harvest and the bread we all break: authoritative, nourishing, essential.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Bringing in the sheaves.”