Can you like Dostoevsky?

Philosopher and linguist Julia Kristeva asks but does not answer this question about the Russian novelist’s complex work.

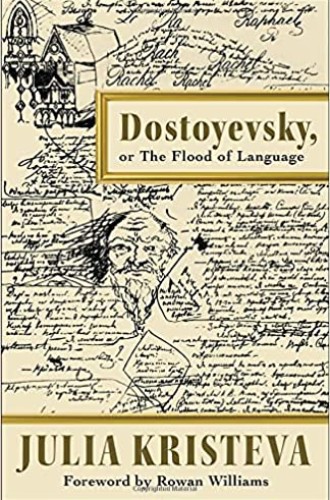

Philosopher, linguist, and literary critic Julia Kristeva’s short book on the writings of Fyodor Dostoevsky juxtaposes vignettes from her own past with observations about the writer who influenced her from an early age. Dostoyevsky, or The Flood of Language should not be approached as an academic analysis. It is, rather, a polymath’s dive through a world of words, her savoring of their emotional and psychological significance as well as their semiotic importance.

Growing up in Bulgaria under Soviet rule, Kristeva was warned off of Dostoevsky by her father, who described the writer as “destructive, demonic, clinging.” He wanted something brighter for her, something clearer, which was why he guided her toward the French language and French thought. At the same time, Dostoevsky was also out of favor with the Stalinist regime, which regarded his work as too religious and obscure.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“Of course, and as usual, I disobeyed paternal orders and plunged into Dosto. Dazzled, overwhelmed, engulfed.” Her initial reading of Crime and Punishment profoundly affected her, but at the same time, she says, “I was in over my head.”

Kristeva went on to study philology and comparative literature in France. There she reread Dostoevsky in French, and once again she found him overwhelming. For Kristeva, the key to deciphering the mysteries of the great Russian novelist was found not in the “lucid sublimation” of French thought but in the writings of post-formalist critic Mikhail Bakhtin. Bakhtin’s critical study Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics was of tremendous significance, not only for introducing a whole new way of approaching literature but also because it signaled a new possibility for freedom of thought. As Kristeva writes, Bakhtin made Dostoevsky a “a social phenomenon, a political symptom.”

From a young woman reading forbidden novels, Kristeva grew into one of the most influential and important thinkers in the field of postmodern critical analysis, which interrogates relations between social orders, psychology, art, and meaning. She was influenced by French structuralists such as Ferdinand de Saussure, who sought to understand culture via structures of meaning in relationships between ideas and reality. For the structuralists, meaning can be scientifically and systematically explored once you have a handle on its basic, objective structures.

But Kristeva, like post-structuralists such as Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, is critical of the assumption that meaning is fixed and complete. She is known for her theory of intertextuality, which characterizes texts and meaning as fluid due to interplays of multiple signifiers and subjects. She developed her own treatment of semiotics called “semianalysis,” which engages texts as ongoing, developing over time. So, for Kristeva, a literary work is not a block of consumable product. It’s something shifting and alive. In simpler terms: the ideas and associations you bring to the text matter. You change it by reading it.

The influence of Bakhtin’s reading of Dostoevsky is significant here. One of his most important observations about the Russian novelist’s poetics is that his work is “polyphonic”—a term derived from a style of music that interweaves independent lines of melody. Bakhtin’s portrayal of Dostoevsky’s polyphony—of the many voices woven together in a narration that is dialogic rather than monolithic—helped Kristeva move beyond structuralist assumptions and further develop her ideas about subjectivity and textuality.

Some of Kristeva’s musings on motifs in Dostoevsky might be perplexing to a reader unfamiliar with Bakhtin’s theories or with Kristeva’s own. Her first chapter is titled, “Can You Like Dostoyevsky?” and it’s a question she does not answer. Rather, she describes her own stages of deciphering Dostoevsky’s work, from Bakhtin’s identification of the polyphonic and carnivalesque, to her mentor Tzvetan Stoyanov’s exploration of complicity and manipulation, to Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic angle on a writer whose characters are beset by neuroses and obsessions.

Kristeva devotes a chapter to Crime and Punishment, possibly Dostoevsky’s most widely read novel, in which the reader follows the unraveling consciousness of Rodion Raskolnikov, a murderer motivated by desire not for gain or revenge but to rise above the mere human, to become a “great man” for whom everything is permitted. Kristeva pinpoints in Raskolnikov’s murdering a fundamental revulsion to the primordial feminine—what she calls “maternal abjection,” another important idea in Kristeva’s thought.

Dostoevsky’s The Idiot centers on the angelically innocent Prince Myshkin, who suffers from epilepsy and emerges as an insufficient Christ figure. In this novel, Kristeva identifies a “primary homoeroticism” between Myshkin and his rival, Rogozhin, whom she describes as a “taciturn bad boy.” In the relationship between the two men, she writes, the beautiful and doomed Nastasya Filippovna is not allowed to be “other than the other’s other.” While her observations illuminate ways in which the male gaze objectifies women, tying this to homoeroticism is indicative of a homophobic trend in Kristeva’s thought, which scholars have critiqued. This trend also emerges in her discussion of the rape of a child in Demons. There are limitations to post-structural “play” on language and text. One of these is an inadequacy of moral seriousness, which we see in Kristeva’s reflections on pedophilia with her unfortunate phrase “irresistible infantile sensuality.”

In The Idiot, Prince Myshkin famously declares that beauty will save the world. It’s a quotation that inspired Dorothy Day but has since acquired a hackneyed feel in circles where conversations about “the Christian imagination” abound. It has become the kind of phrase one expects to see accompanied by a hashtag, advertising something.

But in The Brothers Karamazov, the most polyphonic of Dostoevsky’s novels, beauty is presented as something not salvific but ambiguous and terrible. The story follows the agons of the three sons of a depraved, wealthy old man who is mysteriously murdered. Suspicion falls on the eldest of the sons, the sensual Dmitri. In one scene, Dmitri laments to his youngest brother, Alyosha, that “man is too broad”: humanity contains too much, both the best and the worst. How is it that beauty can inspire devotion to the highest ideals but also tempt humans to the worst depravity? Kristeva sees a similar broadness in the global world we presently inhabit, where “everything is permitted” on the market, and “the ideal of the Madonna is displayed, with no shame whatsoever, side by side the ideal of Sodom.” It is not the first time Kristeva has connected Dostoevskian polyphony with the textual abundance of our extremely online existence.

In this infinitely intertextual world, Kristeva can be read as a trustworthy dispatcher from the terrain of the Dostoevskian imagination, but that does not mean she is easy to understand. Nevertheless, one need not be a post-structural scholar to appreciate how a reading of Dostoevsky’s many voices can help navigate this world’s “unresolvable tensions.”