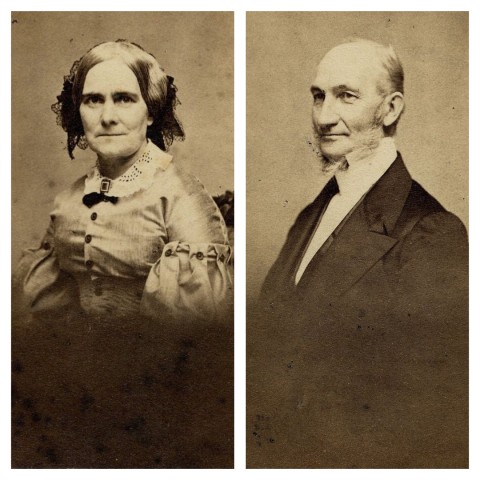

Persia’s first American missionaries

Justin Perkins and Charlotte Bass suffered multiple losses during their missionary years. Was it worth it?

The border between Russia and Persia is cut by the Aras River, which rises in Turkey and empties into the Caspian Sea. In winter months the river is ravenous; it sweeps away footbridges and embankments, swallowing entire villages in its path. The poet Virgil, who knew it by the ancient name Araxes, called this “the stream intolerant of any span.” By the late summer each year, the water is calm and brown and easily fordable.

In 1834, Justin Perkins and his wife, Charlotte Bass, stood at the Aras River with Persia staring at them from across the muddy waters. Young, newly married, and full of zeal for the Lord, they were the first American missionaries ever assigned to preach the gospel in Persia. They left two decades later—Charlotte feeble and broken, Justin an empty shell of a man.

Born in 1805 on a small family farm in Springfield, Massachusetts, Justin came of age in the peak years of the Second Great Awakening. All across New England, bands of mostly young, mostly White, mostly female Christians had begun abandoning the chapels of their parents and congregating instead in large, outdoor “camp meetings,” where they cast off the staid formality of a traditional church service in favor of an emotionally charged, intensely personal religious experience.