What is federally protected land for?

The Trump administration is treating it as plunder. The Antiquities Act saw it as a bearer of stories and wonders.

Deep in the Sonoran Desert, construction crews are blasting through a hill on the Arizona-Mexico border to set the foundation for a 30-foot-high steel bollard fence. This hill, which contains ancient human remains and artifacts, is sacred to members of the Tohono O’odham Nation who live near it. It sits among 33,000 biodiverse acres that were established as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in 1937 and have been designated by the United Nations as an International Biosphere Reserve since 1995.

Meanwhile, the Interior Department has released final plans to allow for drilling, mining, and grazing on large sections of federal land in Utah that were part of Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument until 2017—when the department vastly reduced the size of each monument. This land, which contains cultural artifacts, dinosaur fossils, and ancient rock art, is considered sacred by several Native American nations.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Neither of these shifts in land use is against US law. The Antiquities Act of 1906, which allows public lands such as Bears Ears and Grand Staircase to be designated as national monuments, also allows the executive branch to redefine their boundaries. And the Real ID Act of 2005 permits the federal government to waive archaeological protections, tribal consultation requirements, and environmental rules in cases of national security. The Trump administration evoked such a waiver before beginning the border wall construction in Organ Pipe.

Both instances raise questions about the meaning of the land upon which we live. Do we view it as an object to be divided up for the sake of asserting political power and a generator of resources to increase individuals’ wealth? Or do we see the land the way the Antiquities Act saw it: as a bearer of stories and wonders that existed long before we did?

These questions are heightened by the reality that all of the land within our borders has a long history of life with people who eschewed the idea of land ownership. In the indigenous imagination, land isn’t an object: it’s a living partner in the quest to live well, a holy space that curates the memories and power of those who have come before. To regard a border wall or an oil well as more sacred than the land it occupies is, in this view, idolatrous.

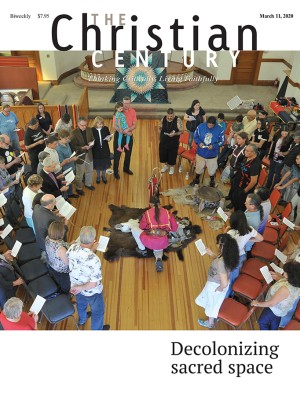

While many Americans view land as something to be leveraged for the money or status it can provide, there are spaces where a different logic is gaining visibility. Terra Brockman writes in this issue about a church body that transferred the title of a building—and the valuable plot of land underneath it—to members of the indigenous nations that had once lived there. This act of decolonization demonstrates that Christian stewardship isn’t always a matter of maximizing financial gain. And it affirms a truth that we often fail to grasp: “We belong to the land,” says Sky Roosevelt-Morris of the Shawnee and White Mountain Apache Nations. “The land doesn’t belong to us.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “What is land for?”