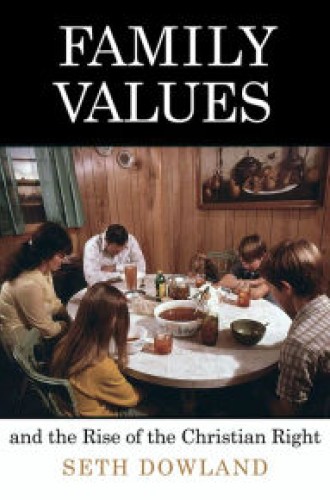

When family values belonged to all of us

The "traditional family" used to provide stability and comfort. Was it all an illusion?

For many years, the slogan “family values” has been connected with Republican politicians and evangelical pastors.

For the 19th-century forerunners of mainline Protestantism, the Christian faith was inseparable from a home headed by male leadership, female nurture, and family prayer. Congregationalist theologian Horace Bushnell argued that genuine faith emerges not from emotional conversions at revivals but rather in the home, where fathers and mothers model lives of love and piety. Countless Protestants argued that wives and children relate to their husbands and fathers in the way that all Christians should relate to God. As the wildly popular preacher Henry Ward Beecher (later to fall from grace in a notorious sex scandal) explained, “family government . . . presents the nearest conception of the way in which God governs the whole realm.”

Well into the 20th century, Protestants of many theological stripes mobilized to defend the family’s sanctity, whether from the scourge of alcohol or from the allegedly baneful influence of Catholic immigrants. (It was left to skeptics such as the author Sinclair Lewis to portray ministers themselves as a threat to the purity of American women.) In the years after 1945, however, evangelicals and their political allies made defending the American family their particular terrain.