The power of small sins

Many Christians can identify the contours of overt bigotry and discrimination. Common examples include an African American being called the n-word, laws prohibiting transgender people from using the bathroom corresponding to their gender identity, or a woman being paid less than a man for the same job.

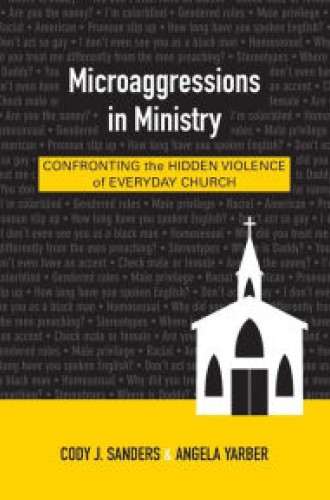

Cody Sanders and Angela Yarber invite readers into the valuable but often uncomfortable wrestling with less recognizable forms of inequity known as microaggressions. Sanders is a pastor and theologian at Old Cambridge Baptist Church in Harvard Square, and Yarber is a theologian, artist, and teacher who consults with churches and denominational bodies. Both authors identify as queer, and both acknowledge their own experiences with microaggressions. Relying on psychologist Derald Wing Sue’s framework, they define microaggressions as “brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain individuals because of their group membership.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Through theoretical analysis, qualitative exploration, and testing the practices of the church, Sanders and Yarber reveal the pain of being on the receiving end of microaggressions. Far from being meaningless slights with minimal harm, microaggressions are mundane spiritual, psychic, and emotional intrusions into the everyday lives of those who have historically been marginalized and oppressed. Although Sanders and Yarber provide a considerable breakdown of the psychosocial dimensions of this oppressive practice in ministry, they fail to frame the issue theologically. A Christian theological assessment of the denial of humanity demonstrated through microaggressions would name it as sin.

Sanders and Yarber offer a voice that is rarely heard in the experiences of people of color, women, and LGBTQ people. They articulate the subtle, nuanced ways in which racism, sexism, heteronormativity, transphobia, and gendered assaults take form. This work is particularly important for progressive Christians and churches, who consider themselves open and inclusive but are often complicit in these silent, hidden forms of emotional violence.

The authors identify three forms of microaggression: “microinsults,” which might be manifested in rude and condescending behavior; “microinvalidations,” which exclude people from full and authentic participation in the life of the community; and “microassaults,” which are deliberate attacks on people based on gender, race, or sexual identity.

Sanders and Yarber provide vignettes of people who have been on the receiving end of microaggressions, and they consider how microaggressions are conceived and arise in worship, preaching, teaching, and pastoral care.

Sanders and Yarber aim to provide practical resources for those who experience individual and communal encounters with microaggressions. One of the most effective ways they do this is with the vignettes that appear in the middle section of the book. Here the authors move beyond theory and explanation, confronting readers with the tangible human reality of individual stories. These stories help readers understand that impact matters as much as intent when a black man’s theology is dismissed by his peers and supervisor in clinical pastoral education; when the newest female member of the church is invited only to teach Sunday school and join the hospitality team; when a transgender deacon is asked by other church members about his “real name.” In these and many other vivid examples, Sanders and Yarber confront readers with the humanity of those who experience microaggressions and the subtlety of the violence they encounter.

For such a thoughtful and esteemed study, the book’s failure to identify sin explicitly and offer a robust theological analysis of microaggressions is a significant omission. Jesus says in Matthew 25, “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” Discrimination and exclusion illustrate our brokenness as human beings who continuously fail to extend the love that is demonstrated in Christ’s ministry. For Christians, identifying and naming microaggressions—confessing them as sin—is a step toward combating them. Such confession brings God into the hearts of individuals and communities and invites the possibility of transformation.