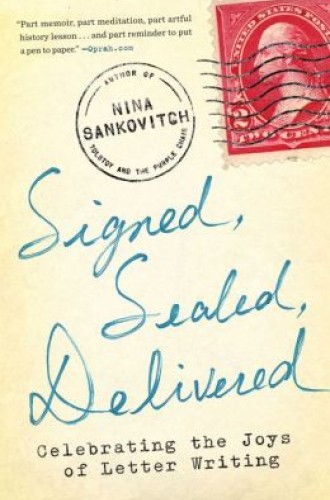

Signed, Sealed, Delivered, by Nina Sankovitch

A member of my congregation is dying at home in the care of a hospice team and his wife, who keeps medications straight and speaks with the pharmacist, doctor, nurses, and aides. She prepares meals and tends to her husband’s personal comfort and other needs. The couple’s daughter reported that one day her father said to her mother, “Would you sit here for a minute and hold my hand?” The daughter continued, “My mother is so busy doing things for my dad she forgets to take time to be with him.”

While there is no substitute for the touch of a loved one’s hand, when that hand is not nearby, a personal letter is the next best thing. Sankovitch writes, “There can be no greater kindness, no greater offering of compassion, than the lessening of sorrow and the bringing of comfort through a letter.”

When Sankovitch’s son left home for college, she wished for letters from him: “A letter, if I am lucky, offers the very smell of my child, his scent on the page, soap or sweat. . . . A letter brings him home again.” From this personal starting point Sankovitch explores the meaning and value of letters in our post-postal age. E-mail, texting, and Twitter are mainstream modes of personal and group communication, certainly for current college students. Letters—considered, composed, and posted—seem like quaint artifacts, the custom and property of older generations.