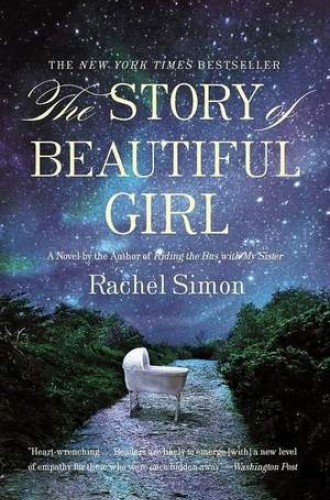

The Story of Beautiful Girl, by Rachel Simon

These days it’s a rare novel that addresses disturbing social issues without flinching and treats religious faith as a force for good, without denying the complexity of either. That combination makes Rachel Simon’s book, newly available in paperback, a pleasure to read and a fine choice for book clubs.

The story begins with a fateful encounter in 1963 between three people: Lynnie, a developmentally delayed young white woman sent as a child to live at the state’s School for the Incurable and Feeble Minded; Homan, a deaf black man taken to the school because people mistook his inability to speak for feeblemindedness; and Martha, a 70-year-old widow living on a farm near the school. Lynnie and Homan try to run away from the institution before Lynnie gives birth to a child, the result of a rape by one of the school’s staff. In a heavy rainstorm they seek refuge at Martha’s house shortly after the baby is born. When people from the school trace them, Homan escapes and Lynnie is returned to the institution, but not before she extracts a promise that Martha will hide and care for the child. It’s 33 years before Lynnie and Homan are reunited, and neither sees Martha again, but their connection is deep and unbreakable. The novel alternates between their stories.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In its squalor and cruelty, the School for the Incurable and Feeble Minded rivals Charles Dickens’s debtor’s prisons and orphanages. Reassured by the school’s hypocritical administrator, parents put away their mentally disabled children there and try to forget them. Since few parents visit or inspect the school, the children are at the mercy of a poorly supervised, overworked and untrained staff. They suffer neglect and abuse. They live closely packed into dreary, smelly cottages where they must share even a toothbrush. The “school” requires them to do menial tasks but gives them no education or training. “They don’t learn anything; they don’t understand anything. . . . They don’t feel pain,” one of the attendants says. Among themselves, the inmates call the school “Sing-Sing” or “the dump.” Homan’s name for it is “the Snare.”

Simon, who has in a previous book, Riding the Bus with My Sister, written movingly about her relationship with her developmentally disabled sister, presents the institution through Lynnie’s eyes—and Lynnie sees and understands far more than most of the staff realize. Intelligent, competent Homan calls her “beautiful girl” and falls in love with her because he recognizes her sensitivity and kindness, not just her external loveliness. Her spirit is nourished in early childhood by her loving relationship with her older sister and, at the school, by the kindness and insight of Kate, one of her attendants. As in a Dickens novel, benevolent rescuers can appear even in hellish places.

Kate nurtures Lynnie’s artistic talent, helps her to regain her speaking ability and teaches her to read simple books. And in time the school changes. After an exposé of conditions, taxpayers insist on reforms, a new administration comes in, and life greatly improves for the residents. By the 1980s the school has closed and the former residents are living in group homes.

While Lynnie’s journey is to become all she can be, Martha and Homan take to the road literally. Hiding Lynnie’s baby, Julia, takes Martha far from her solitary life on the farm. She turns for help to former students with whom she’s kept in touch, she finds unsuspected strengths in herself, and she loves the child, staying steadfast through Julia’s turbulent adolescence.

Homan’s story is the most varied and complex and is likely to linger longest in the reader’s mind. Like Odysseus, he wanders for many years before he finds his way home to Lynnie. Isolated by deafness and illiteracy (he knows sign language, but in an African-American dialect unfamiliar to the people he meets), Homan is often in danger, but his lively mind and competence, to say nothing of a little bit of luck, get him through. He’s rescued and used by criminals, finds ways to survive in an abandoned shack, is sheltered and treated kindly by the devout followers of a charlatan faith healer, travels through the southwest with a crippled young man he rescues from the faith healer, is abandoned in San Francisco, becomes a handyman at a Buddhist retreat center, smokes too much pot, learns standard American Sign Language and how to read and write, and finally forms an imaginative plan for finding Lynnie again.

Simon does an especially convincing job of depicting the consciousness and plight of someone so cut off from ordinary communication. Since Homan has no way of learning people’s names, he names them according to their characteristics. They become Chubby Redhead, Whirly Top, Samaritan Finder, Queen Long Dress. He reads facial expressions and gestures, deciphers motives and plans ways to solve problems. Like Odysseus’s men in the land of the lotus eaters, he nearly loses his goal and purpose as he sinks into drug addiction. But in Simon’s world, people rescue each other and sometimes themselves, and Homan again finds his way.

It’s heartening to read literary fiction in which religious people are depicted with as much respect as Simon’s characters are. When Lynnie’s mother struggles with her husband’s insistence that Lynnie be institutionalized, her rabbi tells her, “I think you’ll regret sending her off. It would feel as if you exiled her into the wilderness.” His wise advice goes unheeded, to Lynnie’s and her family’s detriment.

Kate chooses to work at the school as an act of penance but soon becomes attached to the people she cares for. She is guided by Jesus’ words: “As I have loved you, so you must love one another” and “Whatever you do for one of the least of these, you do for me.” She teaches her children that “every person—from the one-legged veteran who played organ at their church to the stuttering old man who ran the boiler room at the elementary school, to her children themselves—deserved kindness.”

Martha, Homan and Lynnie all, in their own ways, struggle to discern a pattern or purpose to their lives. During a bleak time early in his odyssey Homan remembers one of Lynnie’s pictures. He speculates that a fly landing on a patch of green would see only that green, not the whole picture of many colors. Is there a God, a great artist, who guides and sees the pattern of our lives, though we can discern only one small part at a time? Similarly, as Martha travels from place to place with Julia, she wonders if there is a map for her life, a meaning in what happens to her and the choices she makes.

Neither Homan nor Martha knows how to answer those questions, but as they continue to try to act with integrity and a sense of right and wrong, a pattern does emerge. When Martha begins to research the history of the institutions to which people with disabilities have been consigned, she goes to a chapel and tries to find guidance. But only a question comes: “What can I, just one small person, do?”

The answer arrives a few months later. During a conversation with a recently bereaved friend she realizes that though she doesn’t know whether there is life after death or what such a life might be like, she does know that a place can be heavenly only if people are kind to and help one other. Her students have done kind things for her, and one of them is in a position to investigate Lynnie’s school. She contacts him and the reform begins.

It takes 33 years for Homan to return to Lynnie, and during some of those years he’s tempted to forget his promise to return to her, to settle for a comfortable life with kindly people and his emotions dulled by marijuana. But memories of his brother’s love for him bring him back to himself, and he finds an ingenious way to make it possible to meet Lynnie again. Providence, Simon seems to be saying, is a collaboration between perceptive people and the great Artist who cares about them and works for their good.

It’s possible to dismiss Simon’s novel as a feel-good book, a wish-fulfillment fantasy in which the good people greatly outnumber the bad or indifferent, and in which a beneficent power continually works for our good. It’s easy these days to dismiss such a view as a sentimental denial of the evil and suffering we see daily on the news, if not right around us. But we need narratives that remind us of human connection and kindness, and of the presence of a God who cares for us. How else can we become the kind of people who can help redeem the world?